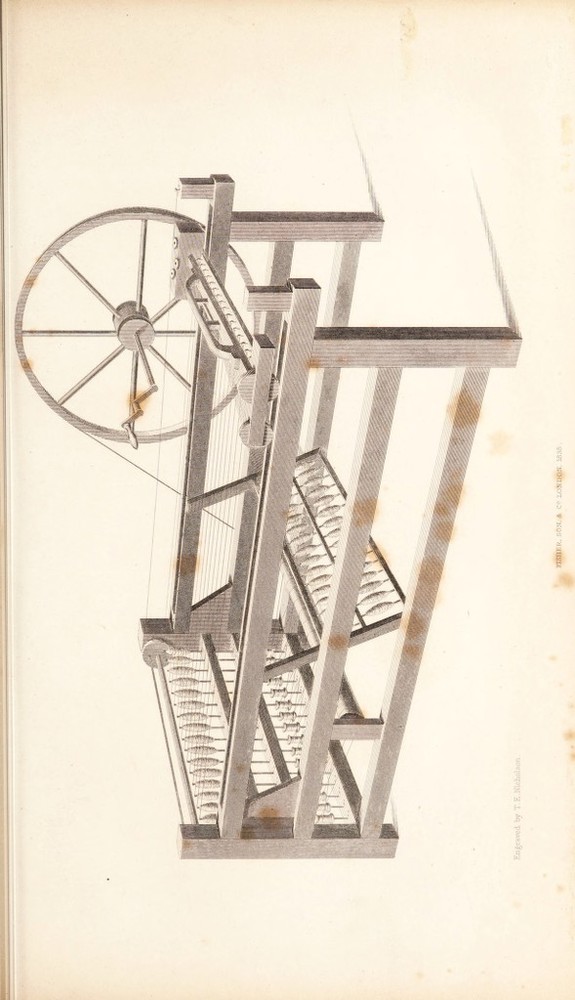

History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain: with a notice of its early history in the East, and in all the quarters of the globe ... and a view of the present state of the manufacture / By Edward Baines, jun.

- Baines, Edward, Sir, 1800-1890.

- Date:

- [1835]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain: with a notice of its early history in the East, and in all the quarters of the globe ... and a view of the present state of the manufacture / By Edward Baines, jun. Source: Wellcome Collection.