Votive offerings, otherwise known as ex-votos, have been a vibrant part of global devotional practice from the ancient world to the present day. Louisa McKenzie explores their role in healing and how they still have a role to play in the secular world of today.

Votive offerings for healing

Words by Louisa McKenzie

- In pictures

It’s impossible to know when the first ex-voto was offered. While the earliest offerings may have been linked to generalised requests for good weather, a bountiful harvest and the like, ex-votos soon came to be most linked with one particular genre of request – deliverance from ill health or danger. Anatomical votives like this Roman example became widespread during antiquity. Ex-votos could be offered as pleas for miraculous healing or in fulfilment of a vow made by the person taking the vow, the votary, that they would make the offering if their request was granted.

As depictions of an afflicted or cured body part, like this Roman votive of viscera, ex-votos embodied the person of the votary. As devotional items offered in extremis, they also embodied the votary’s emotional state at the time of the pledge and donation – anger, hope, faith, relief and gratitude. Today, archaeological and visual records of types of anatomical votives may offer researchers insights into the prevalence of certain illnesses or medical conditions in different time periods.

Ex-voto offerings were not all anatomical. Votive offerings could take on many different shapes and forms. Animals and ships were common forms of shaped votives in antiquity, the Christian tradition and in other religious traditions. This lead example, dating from the sixth century BCE, depicts a horse. If an ex-voto in the shape of a horse was given by a votary because their horse was sick, and the votary had prayed for the horse to recover, this recovery was hoped for because of the potentially detrimental effects on the human votary, a concept sometimes referred to as metonymic substitution.

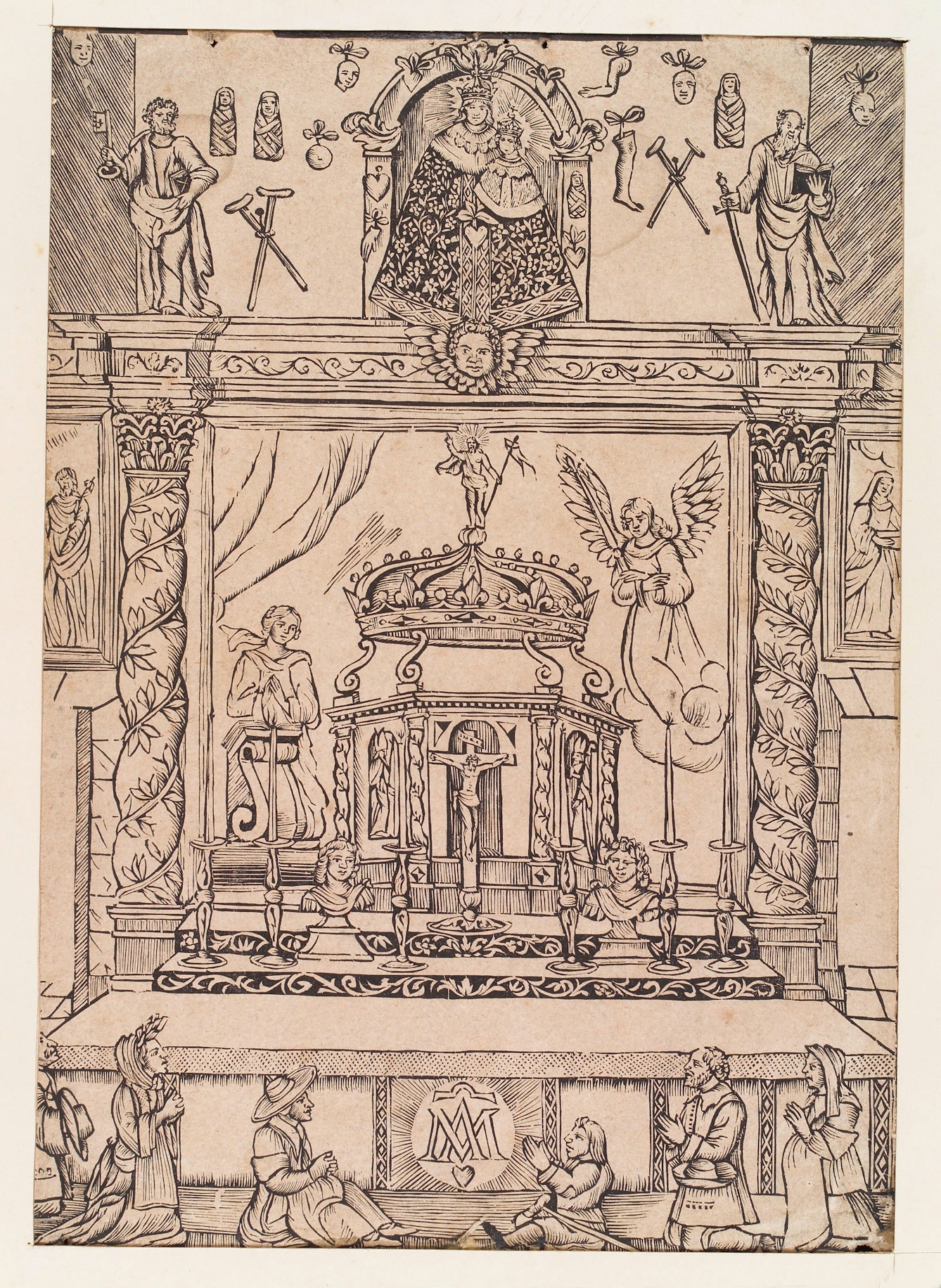

By the 11th century, wax ex-votos were in use in the Christian tradition and many kinds of votive offering were made. Other materials commonly used were different metals and a type of papier-mâché. Several forms of ex-voto became established, such as the large-scale (sometimes life-size) figural ex-voto. These were popular among the rich and powerful, and at certain shrines more than others. Other sectors of the population used smaller-scale ex-votos that were often anatomical, or in the shape of a person, animal or object. This print shows votive legs, stomachs, hearts and swaddled babies hanging above a shrine.

The popularity of votive offerings linked to illness and disease highlights their use alongside traditional medical interventions by those suffering from ill health. The shrine of Our Lady, Star of the Sea at Douvres-la-Délivrande, depicted in this woodcut, was popular with votaries seeking to be cured. According to an historical account, around 1777 one Monsieur Cuiret went to visit the shrine. He had lost the use of both his feet due to illness and come close to death. The innkeeper with whom he was lodging was astonished that Monsieur Cuiret had travelled so far, because he had such good doctors attending him where he lived. The following day, according to the account, Monsieur Cuiret was completely healed after visiting the shrine.

Anatomical ex-votos from antiquity and later examples up to the Middle Ages do not usually show the affliction or injury on the body part concerned. Rather, they depict the wished-for or received outcome of the vow – a whole and healthy body part. However, later examples, such as this 19th-century limb, may show the affliction or injury. It is possible that these later examples were influenced by the narrative format of a different kind of ex-voto, the votive tablet, which had started to become popular from the 16th century.

Votive tablets were particularly widespread in Italy, where they are known as tavolette. This example, probably dating from the 18th century, depicts a woman being dragged, seemingly lifeless, from a well. The rescuer cries out to the divine intercessor – the Virgin and Child shown in the top right of the image. Relatively small, tavolette were usually painted with a scene depicting the votary’s misfortune, a prayer to the divine intercessor and, sometimes, deliverance. These dramatic scenes emphasised the miraculous closeness of votary and intercessor at the moment of peril. The initials PGR are found on most votive tavolette and stand for per grazia ricevuta (for received grace). These initials symbolise the contingency of the votive gift. The votary has received the grace they asked for – salvation from danger or disease – and thus the votive tablet is given in thanks for the answered prayer.

Votive tavolette not only fulfilled the vow made by the votary. They also had an important commemorative function, highlighted by the expanse of tavolette displayed at this church in Deruta, Italy. Display en masse of any votive objects at a shrine also attested to the shrine’s popularity as a miracle-working site. Votive offerings thus acted as forms of advertising for the shrine’s successes, potentially attracting more pilgrims and their offerings. Multiple ex-votos would also have had a strikingly transformative effect on the visual environment of the shrines at which they were presented – shrines would not have been seen in isolation but surrounded by or covered in votive offerings.

Votive objects are not confined tothe ancient European and Christian traditions. This 11th/12th-century terracotta plaque is an example of a type of ex-voto in use in the Buddhist tradition from its earliest period. While the Buddha is the consistent central figure on these plaques, both his pose and the surrounding iconography can vary. This example presents Buddha in the bhumisparsha mudra (earth-touching gesture). Plaques depicting this gesture are often associated with the shrine of Bodh Gaya in India. Traditionally, the votive plaques were made of clay and presented by pilgrims at Buddhist shrines as a token of the votary’s faith and devotion.

Ex-votos are not just a thing of the past. They continue to be in use today at shrines across the world. These shrines can be religious or secular, or combine elements of both. Recent work by Anne Hilker and Alyssa Velazquez has persuasively argued that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC effectively became a site of secular votive-giving – either in the hope that those who were missing in action would be found, or in commemoration of those lost. The ability to transcend religious/secular boundaries is testimony to the emotional force inherent in all votive-giving.

About the author

Louisa McKenzie

Louisa McKenzie has a PhD in art history from the Warburg Institute. Her thesis, funded by a London Arts and Humanities Partnership (AHRC) Studentship, considered the economic and devotional lifecycles of wax ex-votos in Florence 1300–1500. She researches the art and material culture of late medieval and early Renaissance Florence.