From Ancient Greek “memory palaces” to symbols, pictures, annotations and rhymes, Julia Nurse explores some of the ingenious and sometimes beautiful mnemonic methods that we have devised to help us to remember.

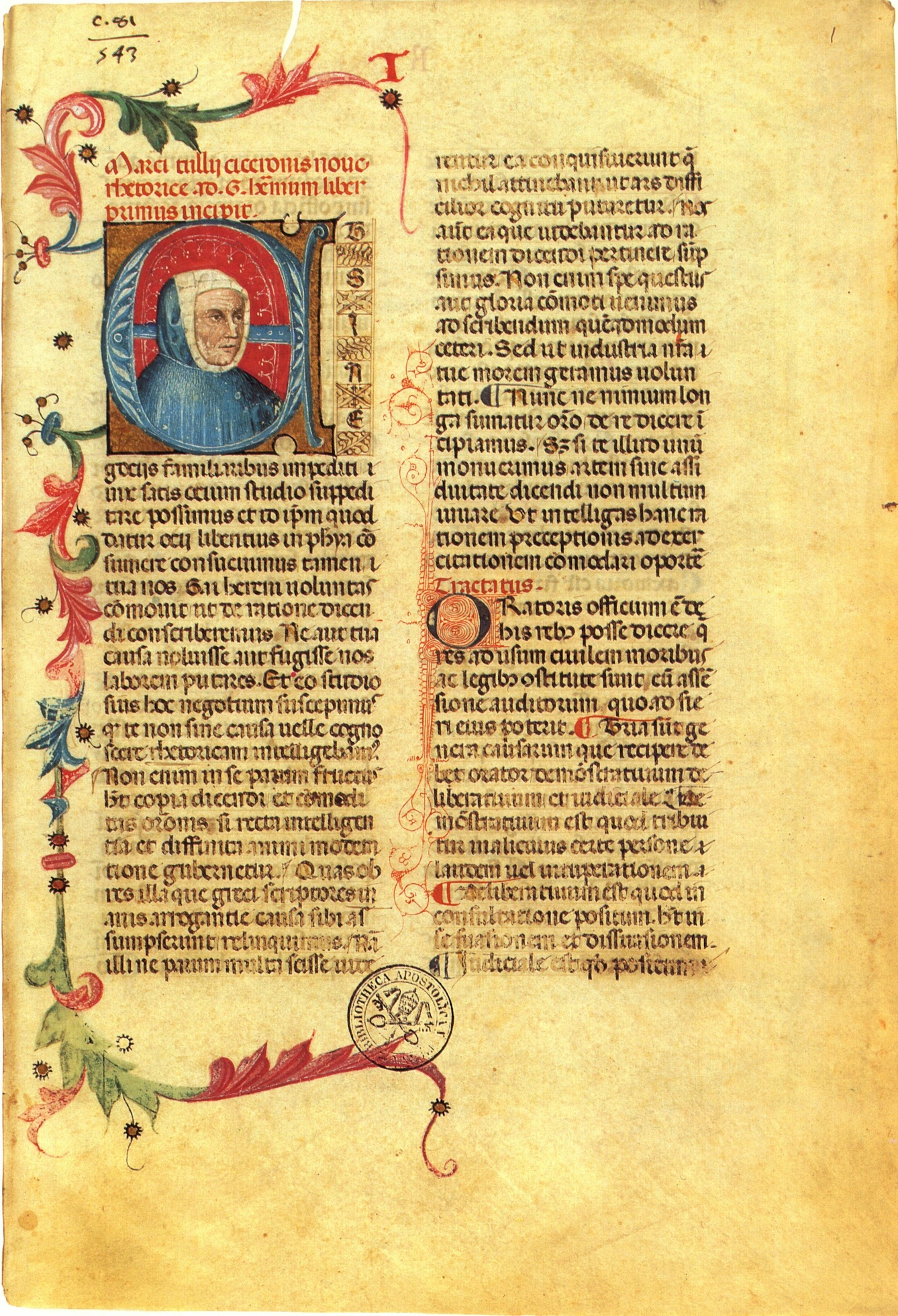

Mnemonics were of great interest to scholars writing treatises on rhetoric. They thought that there were two forms of memory: one that is natural, and the other artificial. Memory aids were artificial. Cicero’s ‘Rhetorica ad Herennium’ is believed to be the earliest treatise on mnemonics, from about 90 BCE. Translations of this text were still circulating hundreds of years later, in the 16th century.

Visual memory aids have been used for centuries. Ancient philosophers like Aristotle used the loci method, which used familiar places to help to recall information. Simonides of Ceos showed how this worked: he stepped outside for a moment during a banquet and returned to find that the hall had collapsed and everyone inside had been killed. Simonides was able to identify the remains of the feasting guests because he had memorised where they had all been sitting.

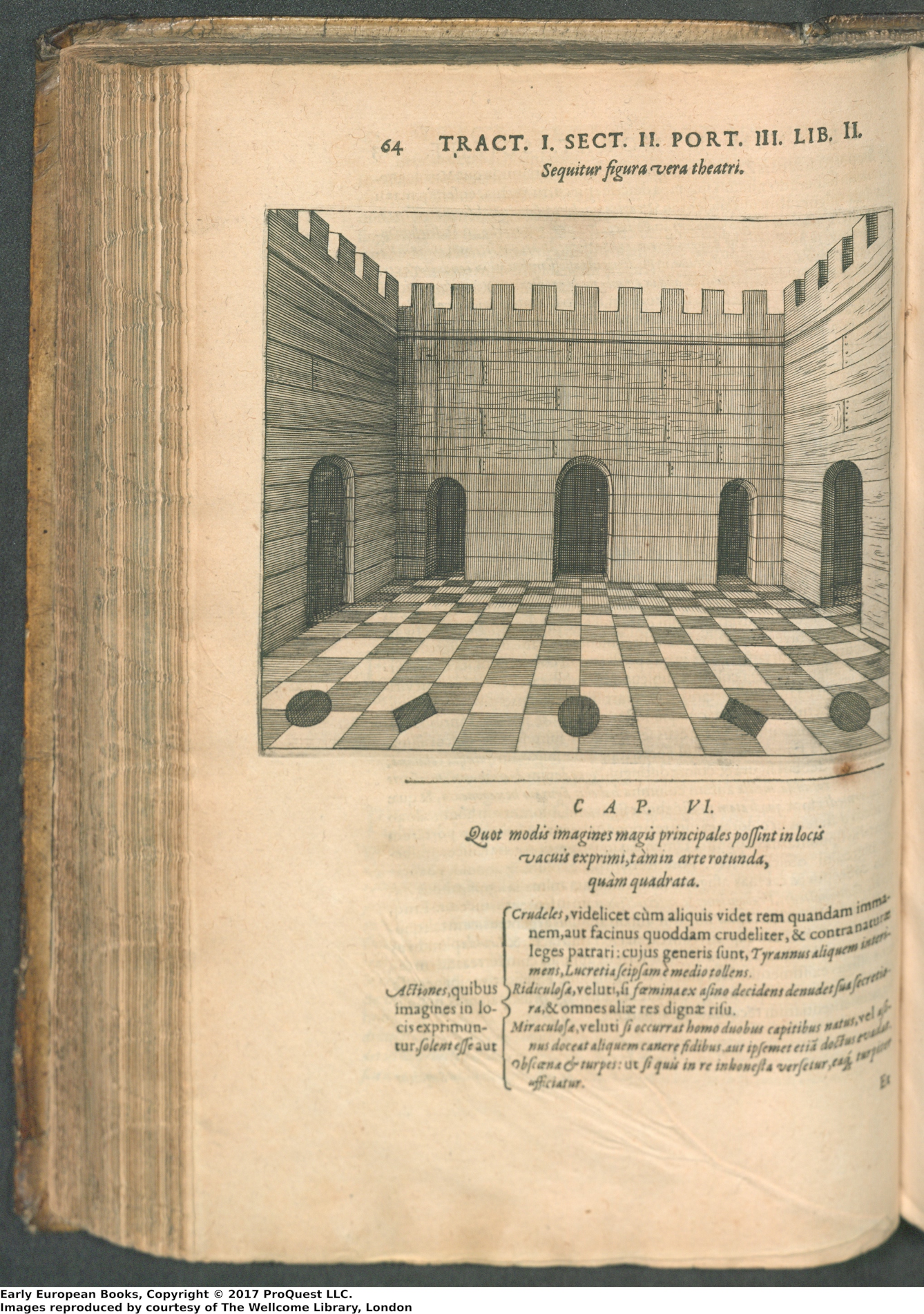

The art of memory, or Ars memoriae, was debated and illustrated in publications throughout the medieval and early modern periods. This book about mnemonics from 1619 by Robert Fludd uses the loci method of place to build a memory palace in the form of an imaginary classical stage with five entrances.

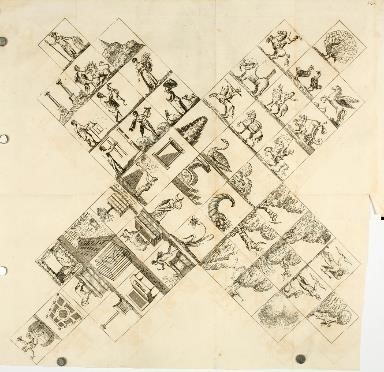

Later, Gregory von Feinaigle credited his marvellous memory to the locality method too. He encouraged students to imagine a set of rooms that told a story, with symbols for what required remembering. His technique is illustrated in ‘The New Art of Memory’ (1812), where symbols appear in ‘rooms’ to help memorise the succession of the monarchy. For instance, the symbol of the peacock – a visual representation of pride and vanity – (top far right) represents Henry VIII.

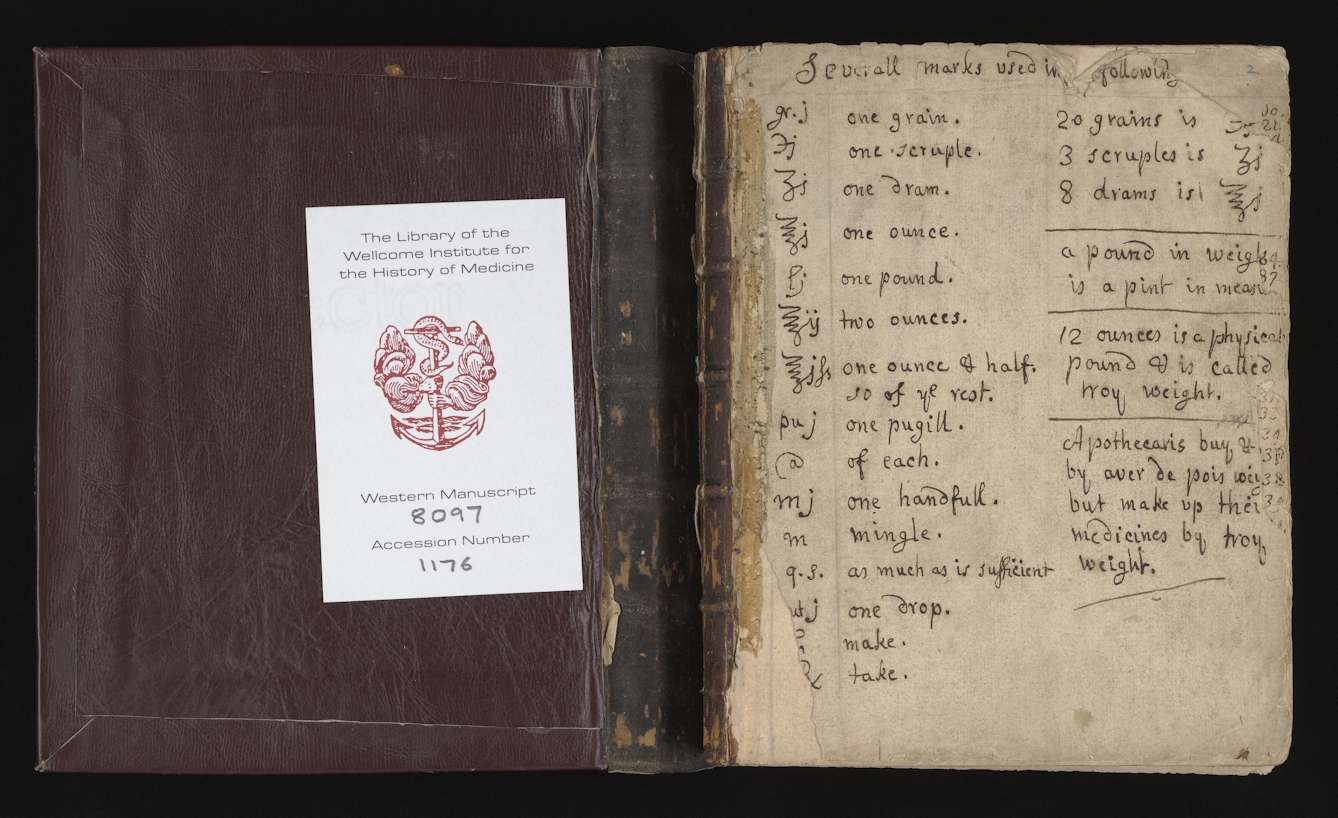

The peg system for remembering was also devised by the Ancient Greeks. ‘Pegs’ acted as triggers to help recall a specific order. This 17th-century book of medical recipes shows an example of this space-saving method, with symbols for commonly used measurements written at the front of the book.

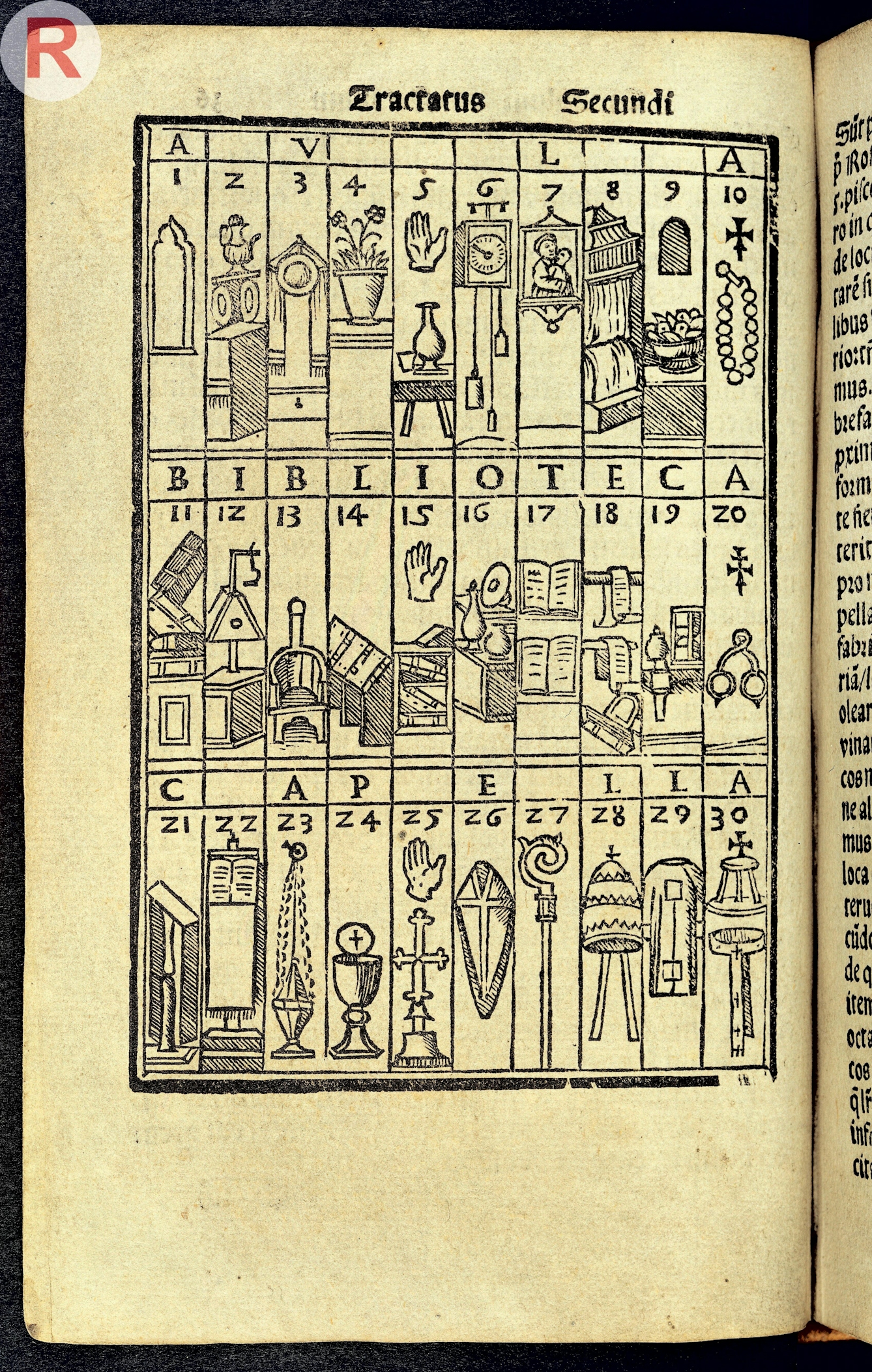

Another place where we might see ideas ‘pegged’ to images are visual alphabets such as Johann Romberch’s ‘Congestiorium articiose memorie...’ from 1533. These were frequently used to educate young people and employ the same principle as alphabet card games used for children learning alphabets today.

Images can be evocative of quite complex philosophical ideas. Aristotle once queried whether man can be described as a biped even if individual men do not have two feet. This mnemonic visualisation likely represents this idea through its depiction of a man with a wooden leg carrying a basket of arms and legs. There is little explanation for this in the text, suggesting the reader was expected to remember the association.

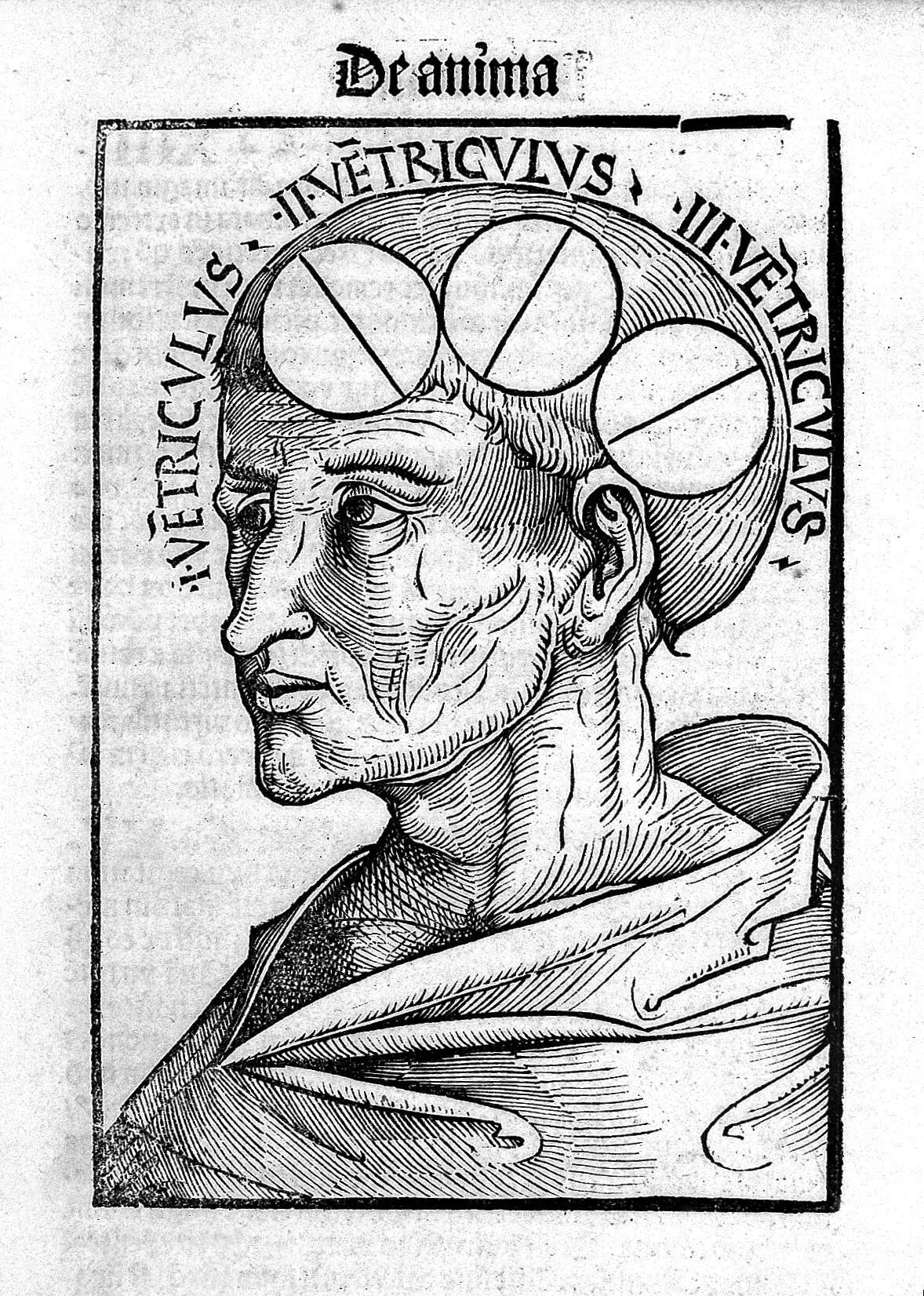

Albertus Magnus similarly used visual aids to help his readers to recall detailed ideas. Magnus developed ancient theories about memory in the medieval period. In this illustration from a 1506 edition of Magnus’s ‘Philosophia naturalis’ (‘A Natural Philosophy’), brain functions are represented in three circles in the forehead area (common sensory input and imagination), just above the ear (fantasy and estimation), and at the back of the head (memory and motion). These functions are not labelled, presumably because the reader was expected to have memorised them.

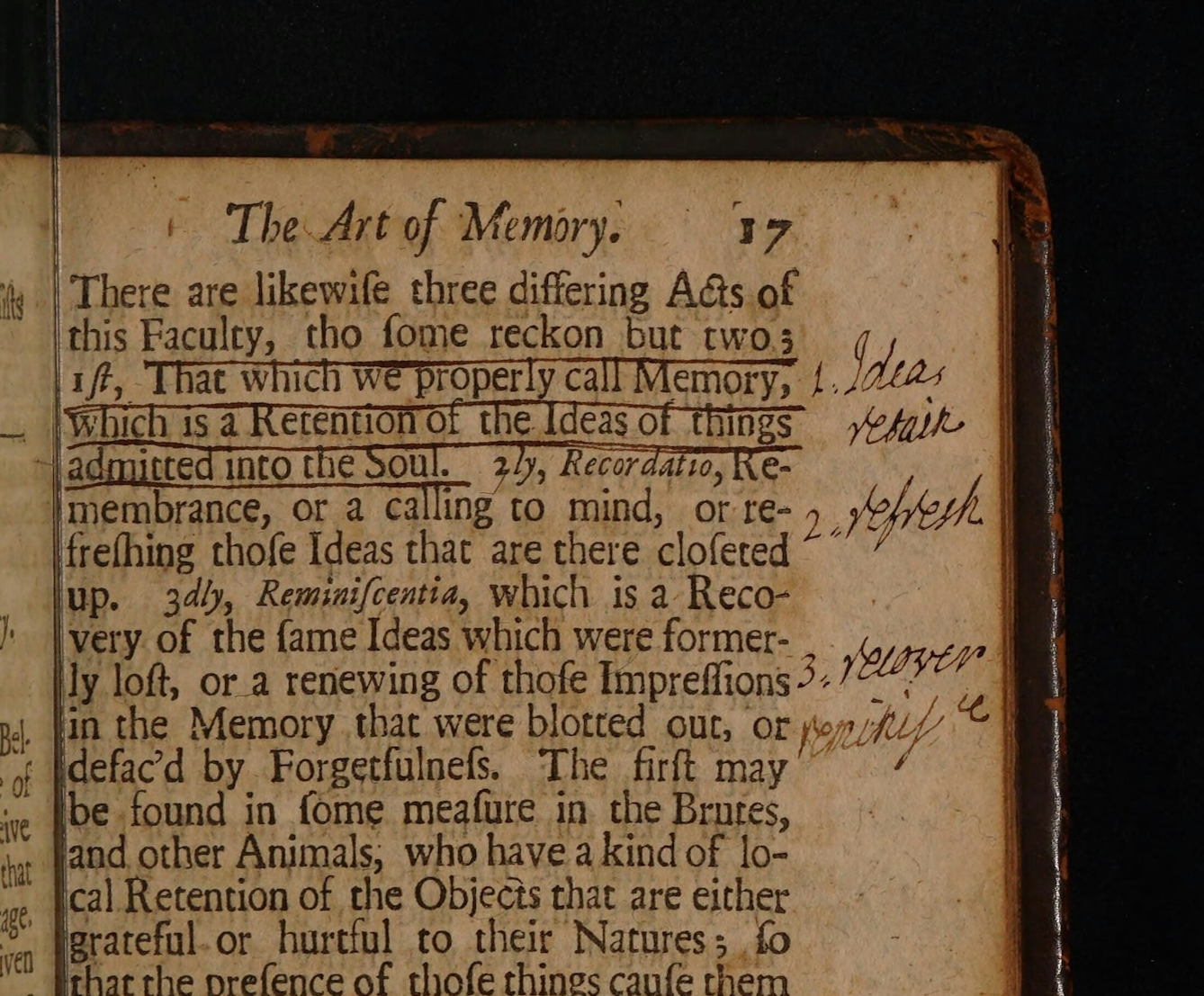

Another book in our collections is similarly meta in the way that it bears evidence of a method of recall that has been applied to a text about remembering. Writing things down appears to have helped the owner of this book, ‘The Art of Memory’ from 1699, to memorise this text. The owner, perhaps a young student, repeatedly annotated and categorised key points.

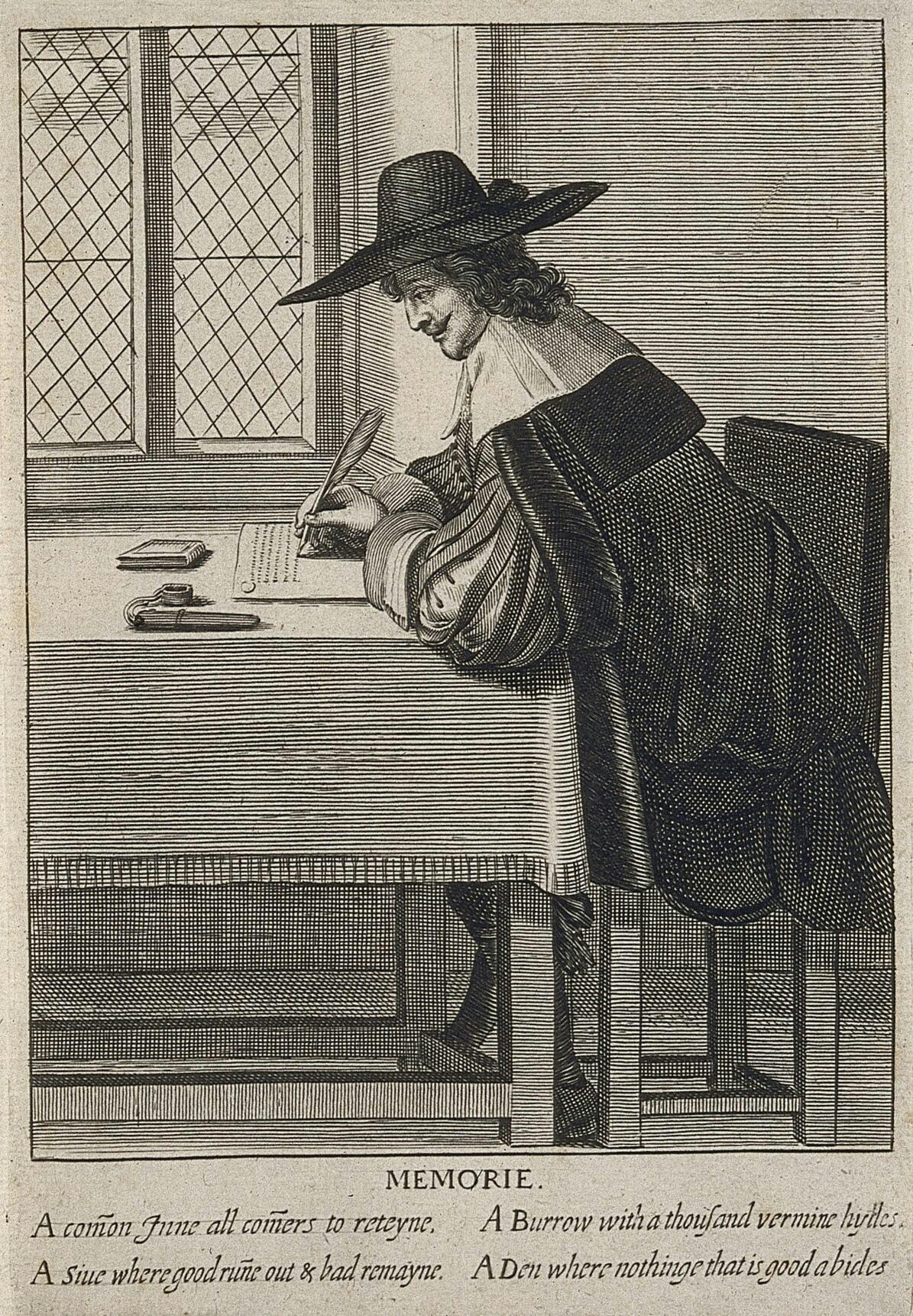

Writing aide-memoires was encouraged in the 17th century. This print depicts a man writing as a representation of the faculty of memory. Writing things down is still a technique that many of us use to commit information to memory, even if we do not keep our notes.

Writing in very specific forms, such as anagrams and acrostics, is another time-honoured method of remembering. This example from the 18th century bears the memorable title ‘Peas for swine! and grapes for citizens! or The Monster! An Acrostic’. An acrostic mnemonic is a sentence or poem where the first letter (or letters) of each part of the text represents a thing that you’re trying to memorise. It was often used in religious contexts and continues to be used in educational literature today (Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain might still be lodged in your brain, for instance!).

When cognitive functioning – thinking, remembering and reasoning – fails to work correctly, dementia kicks in, particularly in old age. The word ‘dementia’ itself is used as a mnemonic for assessing dementia triggers: D represents drugs, E for eyes and ears and vision loss, M for metabolic disorders, E for emotional causes, N for neurological and nutritional deficiencies, T for tumours and trauma that have similar symptoms, I for infection processes and A for alcohol.

Throughout history, we have also made ideas more memorable through song and rhyme. Recipes in verse often appeared in texts for medical professionals from the medieval period onwards (for example, Honoré Joseph Pointe’s 18th-century anatomical mnemonics, Ms.3929). In some cases, earlier popular mnemonic verses used in medieval recipes reappeared centuries later, as can be seen in this apothecary signboard from the early 19th century, which features part of a verse that originally appeared in a 15th-century Gaelic medical tract.

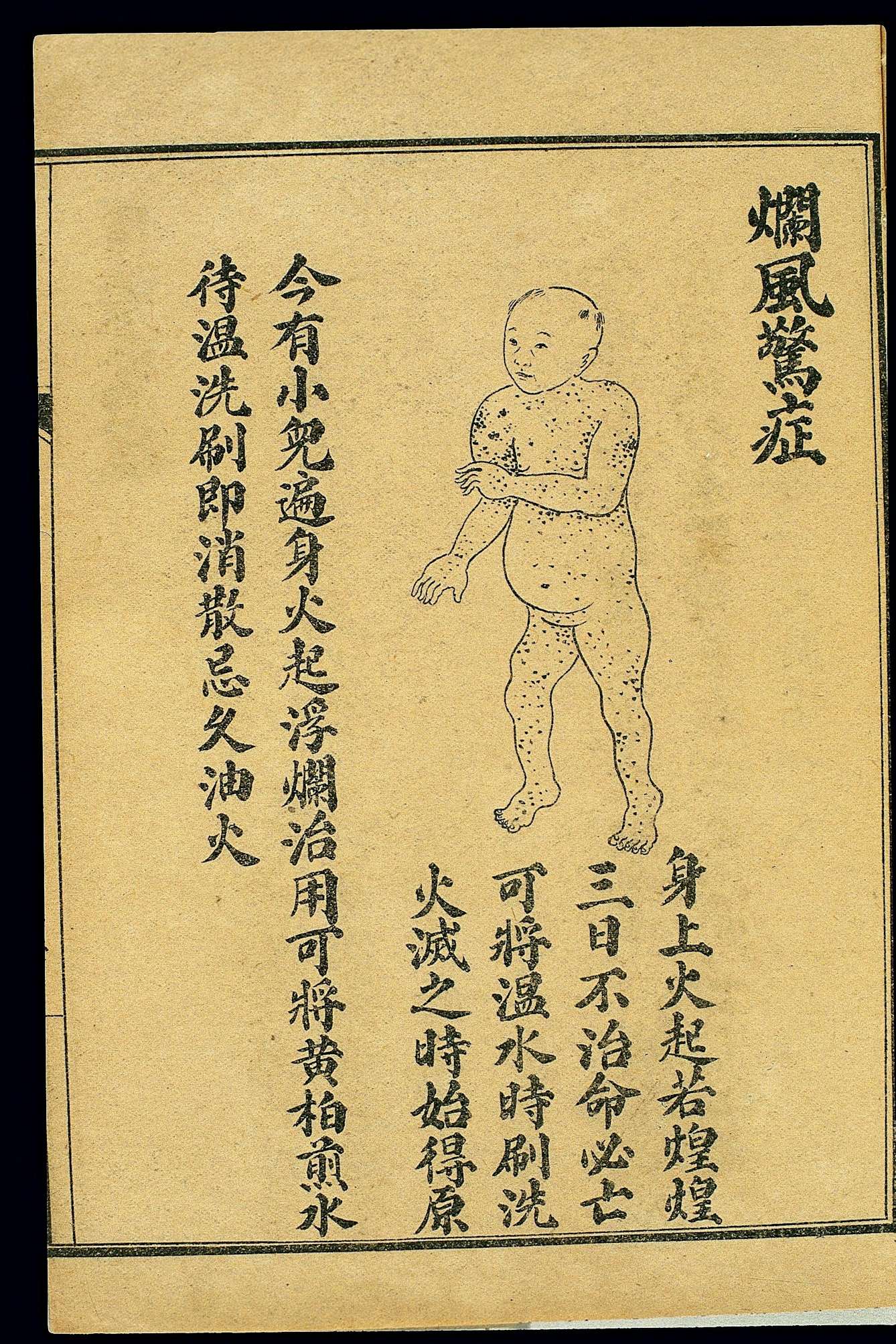

Some authors have brought together many of these different techniques, using words, verse and images so that they all might work together to help someone to remember something important. This illustration of a boy suffering from “putrid wind” is an example of how Chinese acupuncture charts helped to remind a physician of key pressure points and their associated healing function.

If you needed further inspiration to try out mnemonics yourself, there is now research indicating that using visuospatial mnemonic devices might help prevent or at least slow down the process of age-related memory decline. Anyone can make a mnemonic device, but if you need a helping hand, the NASA Cognition Lab has developed a handy tool known as the ‘Mnemonicizer’ to make your own.

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She currently runs the Exploring Research programme, and has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.