From the first reports of AIDS in Scotland, individual activists and organisations have sought to educate and protect their local communities. Historian Colin Moore shows how their campaigns evolved from simple pamphlets to fun and innovative messages incorporating sex, comics, football, and even a bright pink bus.

Telling Scotland about AIDS

Words by Colin Moore

- In pictures

Scotland has set its own course for healthcare, even before devolution. This is clear from the Scottish response to the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. Though also covered by the UK government’s well-remembered ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ campaign (1986), the Scottish experience of HIV/AIDS was powerfully shaped by smaller, local initiatives.

In Edinburgh, Derek Ogg, a lawyer, and Sandy McMillan, a doctor, were among the first to respond to the snowballing AIDS crisis in Scotland. Ogg later recalled a night out in Edinburgh’s most notorious gay club, Fire Island (premises pictured above), when he realised “this is all going to change and they can’t see this coming”. A short time later, Ogg and McMillan returned to Fire Island – on a busy Friday or Saturday night – to deliver their first lecture on AIDS. They went on to give talks at queer venues all around Scotland – a simple but effective form of communication.

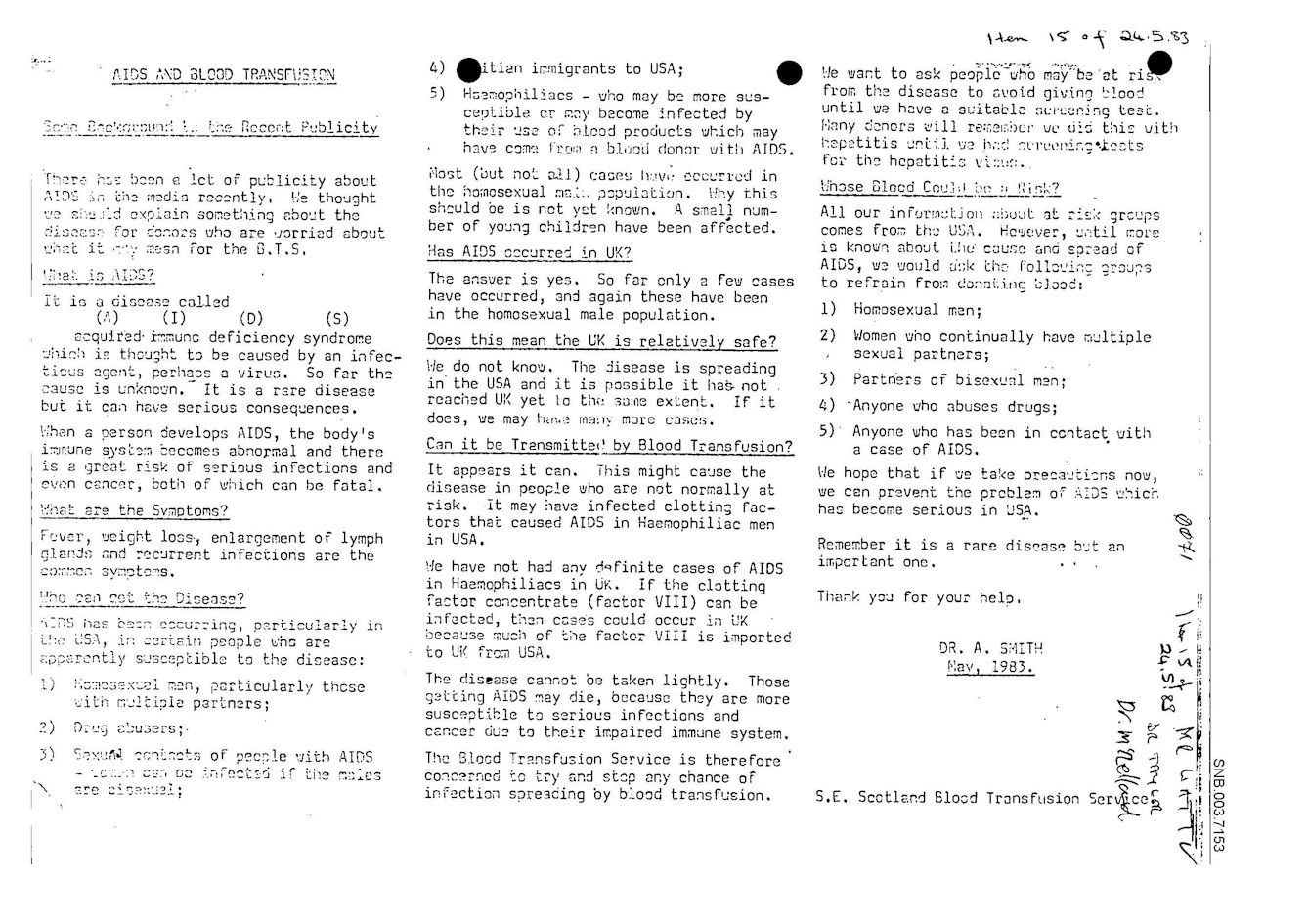

There were no official attempts to intervene in the AIDS crisis in Scotland until the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) produced a pamphlet in 1983 about who should and who should not donate blood. Not only was the pamphlet uninformative, but it was also laced with homophobic and biphobic language. It conflated the supposed risk of all homosexual and bisexual men with that of heterosexual women “who continually have multiple sexual partners”. The Scottish Human Rights Organisation (SHRG), of which Ogg was a member, criticised SNBTS for amplifying the dangerous stereotype that all gay and bisexual men were promiscuous and perpetuating the myth of AIDS as a “gay disease”.

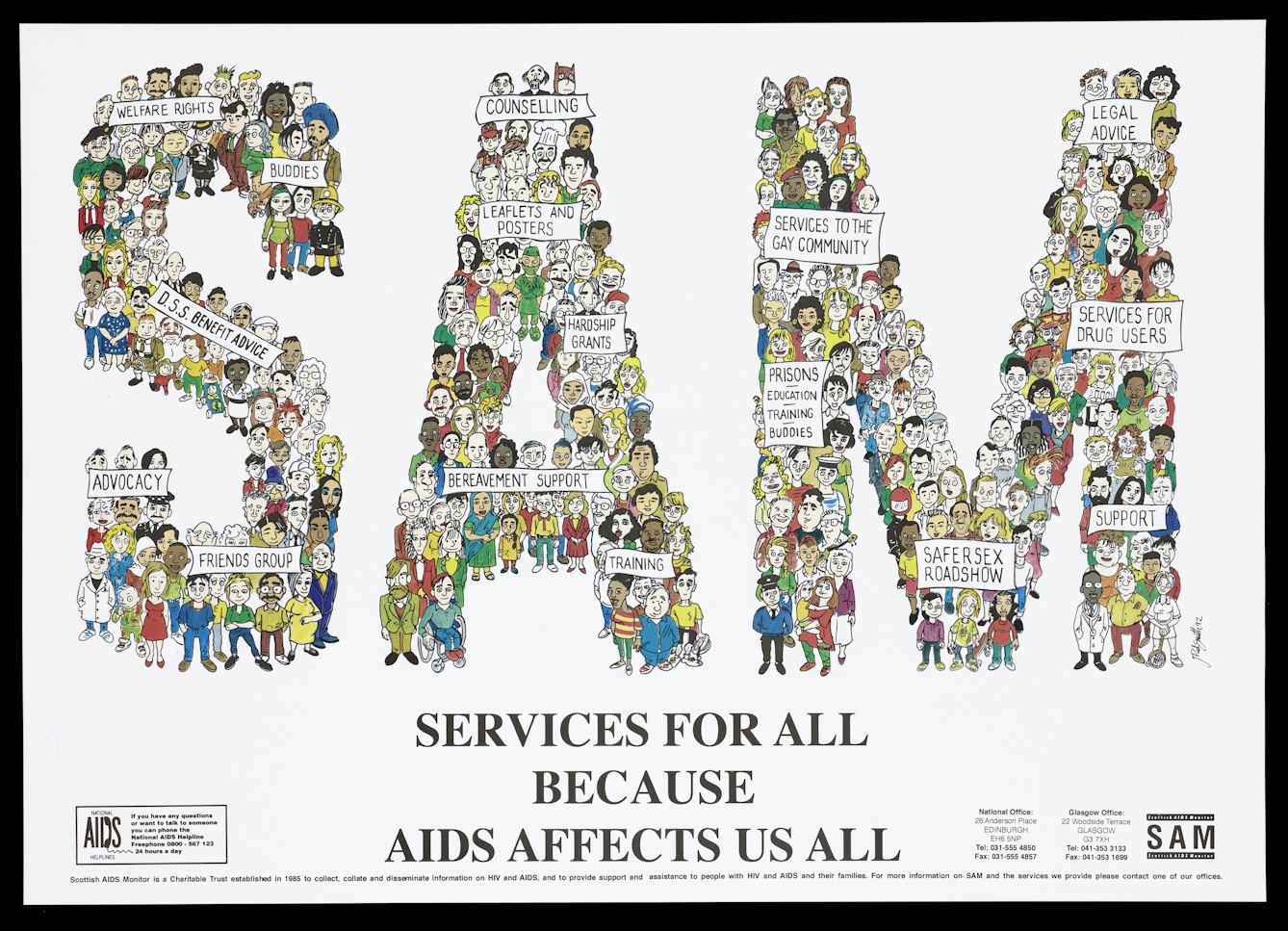

Ogg, McMillan, SHRG colleagues and the SNBTS collaborated to create an AIDS monitoring group, later known as the Scottish AIDS Monitor (SAM). SAM was devoted to communicating accurate, up-to-date information. To achieve this, it cultivated a close working relationship with Scottish medical organisations and physicians. As an Edinburgh blood-transfusion consultant put it, SAM was “desperately needed to combat the rumour and misinformation being spread”. Initially SAM continued as Ogg and McMillan had done – spreading prevention information through in-person speeches.

SAM began producing information pamphlets in 1984 to reach a larger audience. The first of these, ‘AIDS – The Facts’, communicated what little knowledge experts could agree on at the time. As significant critics of the SNBTS pamphlet, SAM needed to ensure that their material was beyond reproach. It was soon followed by ‘AIDS – The Latest Facts’ (1985), which included updated information. Both pamphlets conveyed information in a formal, plain and unengaging manner, much like the ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ and the Scottish Health Education Group (SHEG) pamphlets that would circulate in the following years.

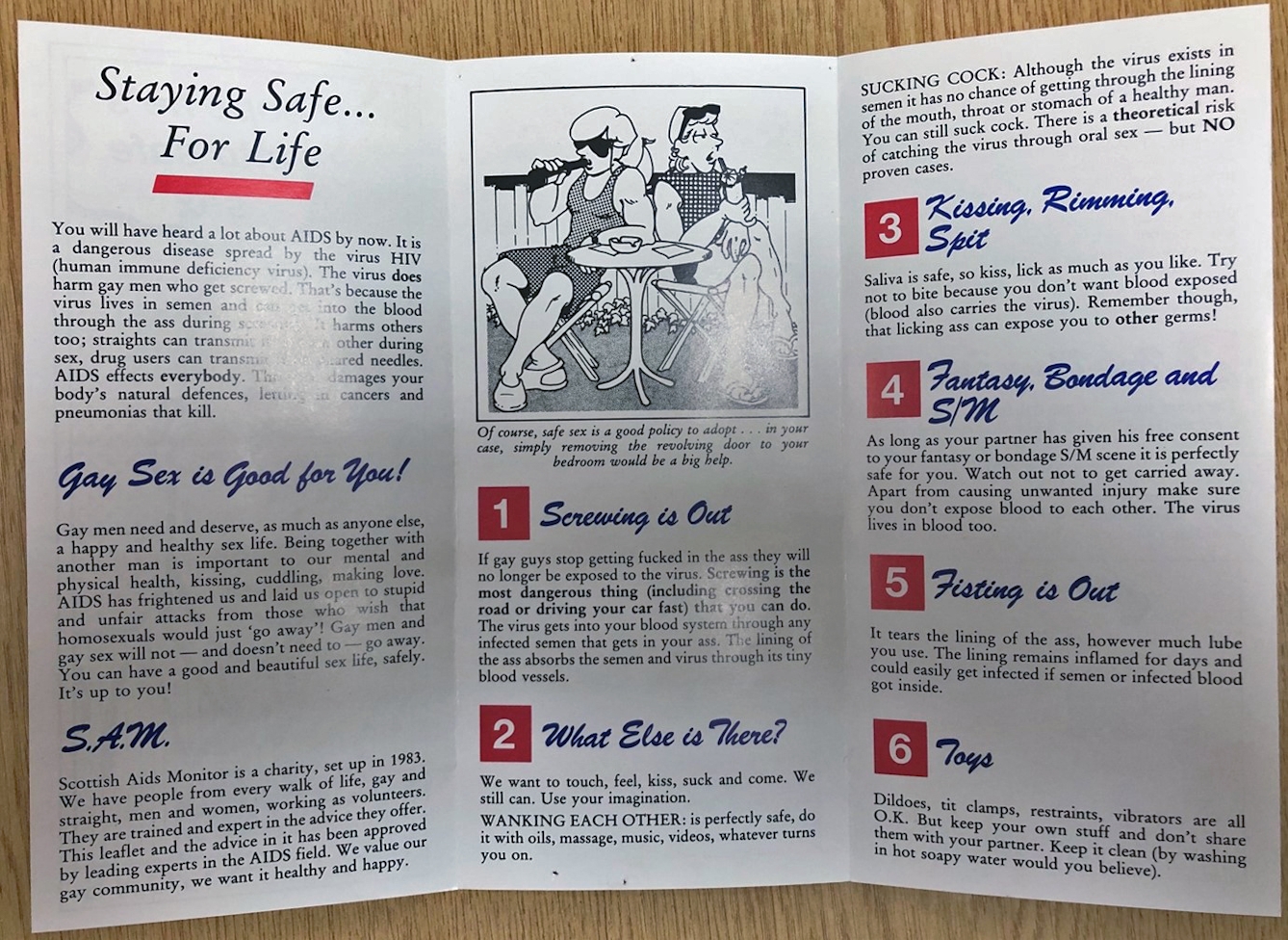

SAM’s communication strategy evolved significantly as the decade wore on. The group pivoted from producing dry, informational pamphlets to material that sought to engage readers through humour and titillation. For instance, the ‘Staying Safe… For Life’ pamphlet was risqué, humorous, and featured cartoons that added levity to a difficult topic. Striking a more sex-positive note, it provided realistic guidance for specific sexual practices and alternatives.

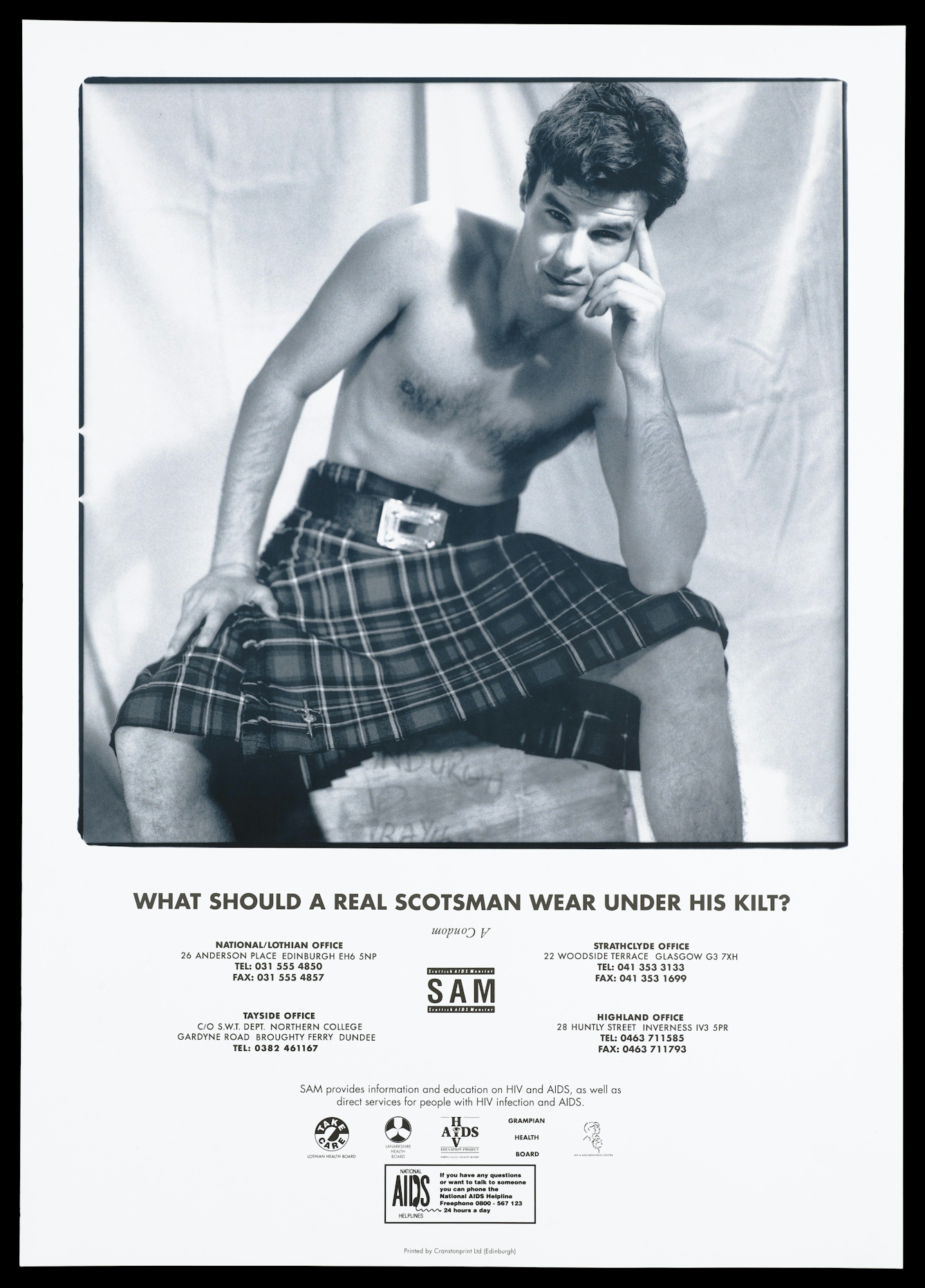

The success of ‘Staying Safe… For Life’ emboldened SAM to double down on sexual content and imagery. From 1987 onwards, the organisation took out a series of risqué advertisements in Gay Scotland, a bimonthly magazine with several thousand readers. The nude and semi-nude visuals were intended to draw in the reader and encouraged them to have safe sex and to consult guides on safe sex.

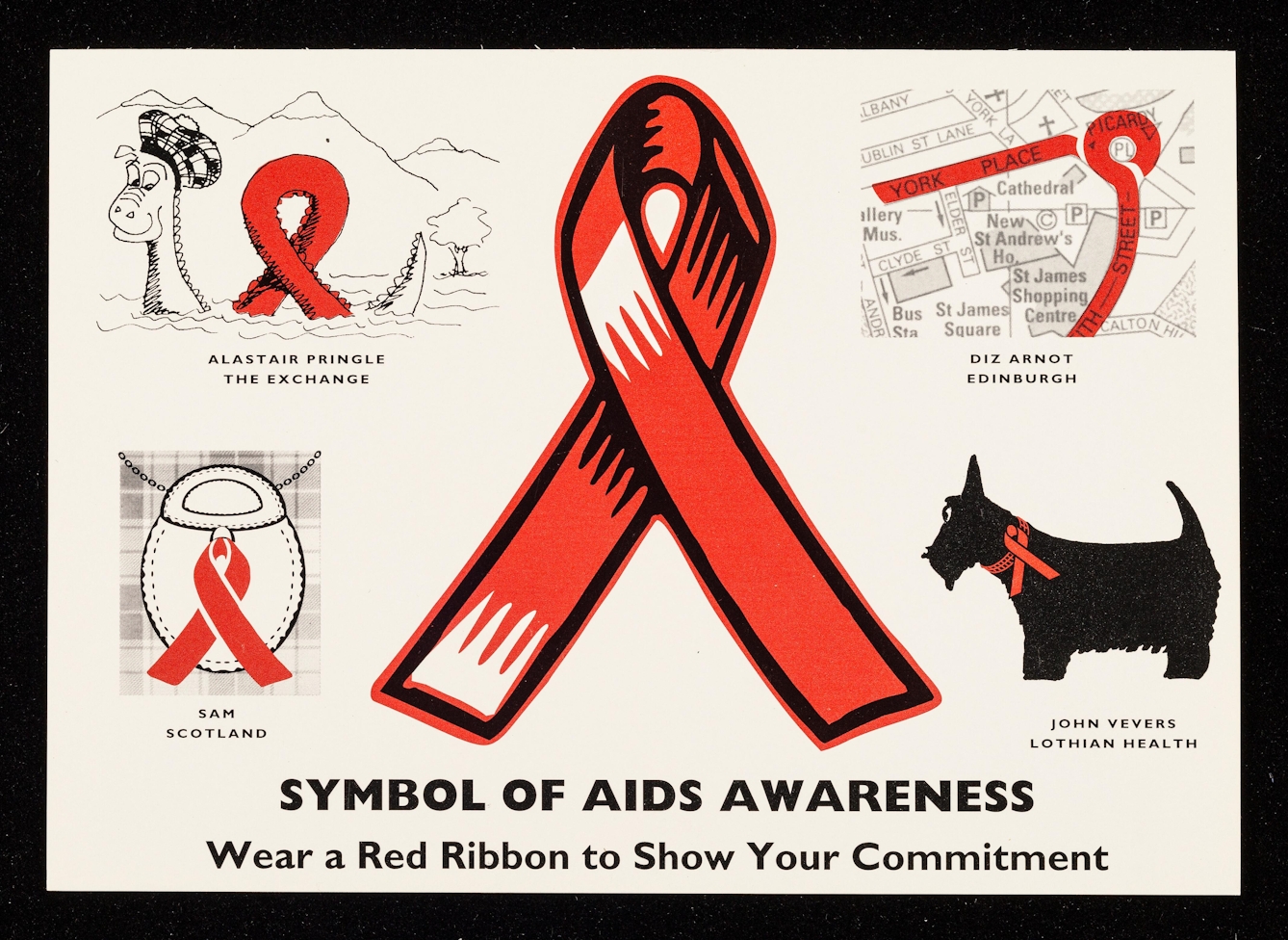

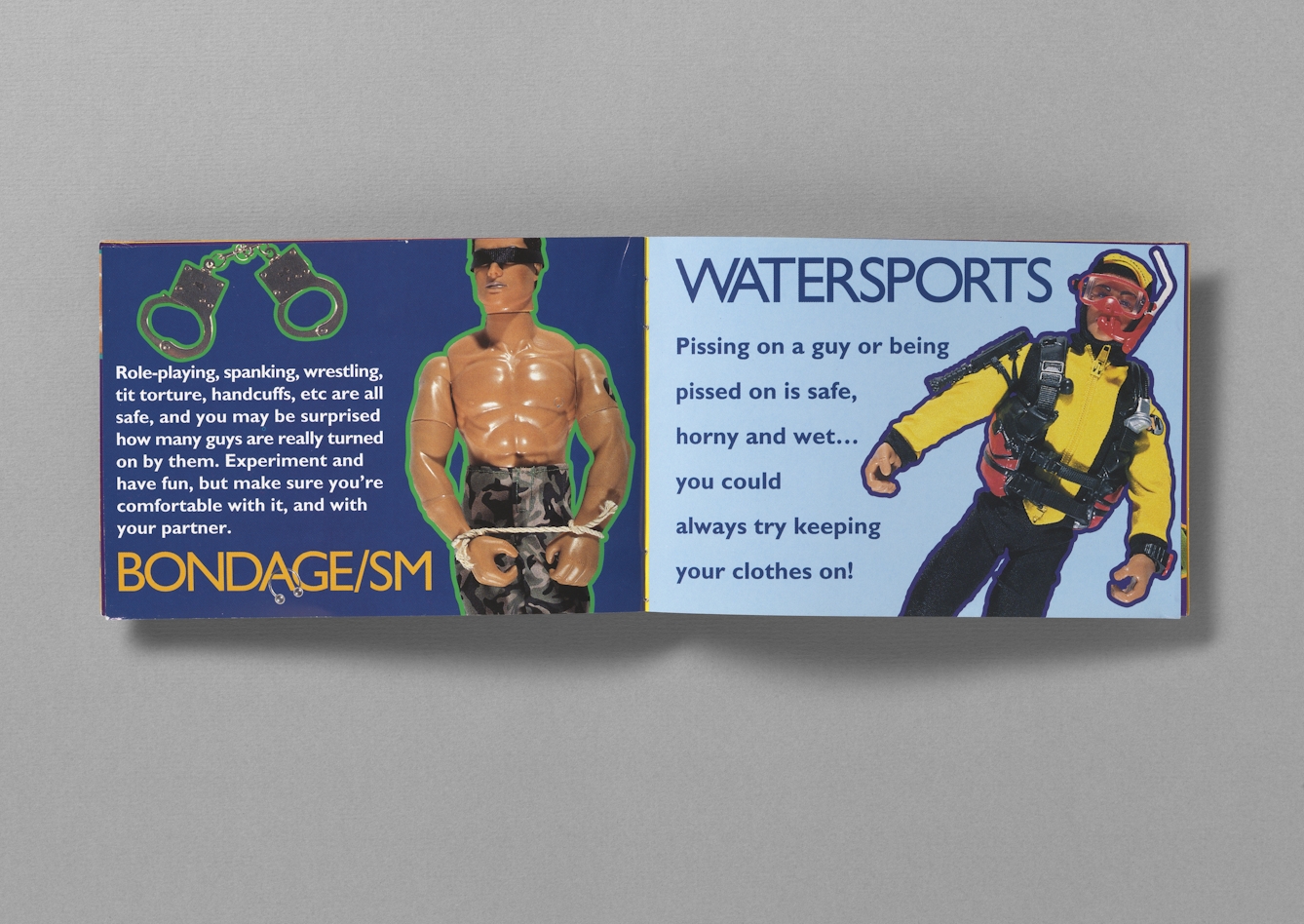

Throughout SAM’s lifespan, they continued to produce provocative media that drew in the reader in with creative imagery. However, their stylistic choices evolved over time, challenging the concept of what an HIV/AIDS pamphlet could be. This can be seen above, where SAM have used an Action Man figurine to communicate safe-sex advice for those who enjoyed various fetishes.

The availability of cheap heroin in Edinburgh and other popular intravenous (IV) drugs elsewhere in Scotland resulted in an increasing number of heterosexual Scots testing positive for HIV and new awareness campaigns to highlight the risks of passing on AIDS via needles.

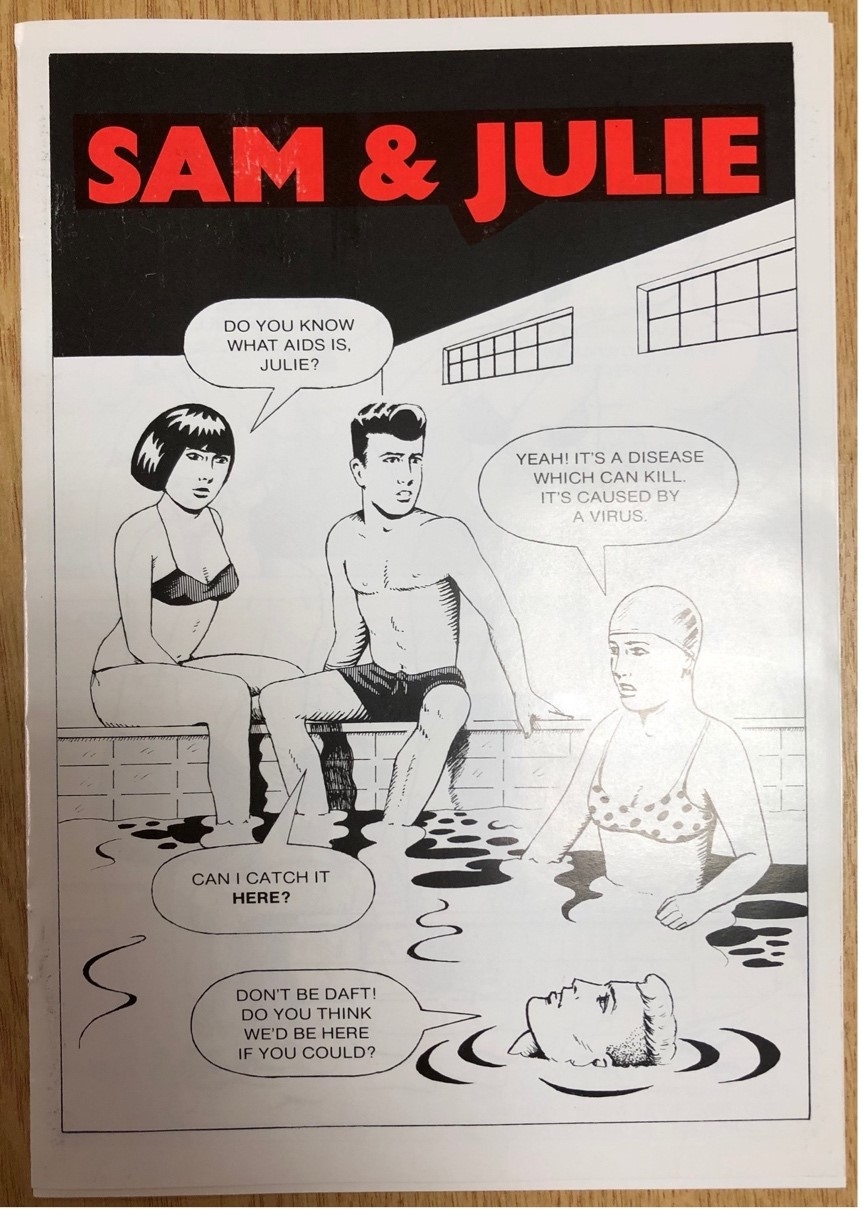

As cases continued to skyrocket, Edinburgh became known as the ‘AIDS Capital of Europe’. To educate this new audience, SAM developed new materials aimed at heterosexuals. Engaging comic strips, such as ‘Sam & Julie’, tackled myths that HIV could be transmitted by swimming in a public pool or eating at a restaurant.

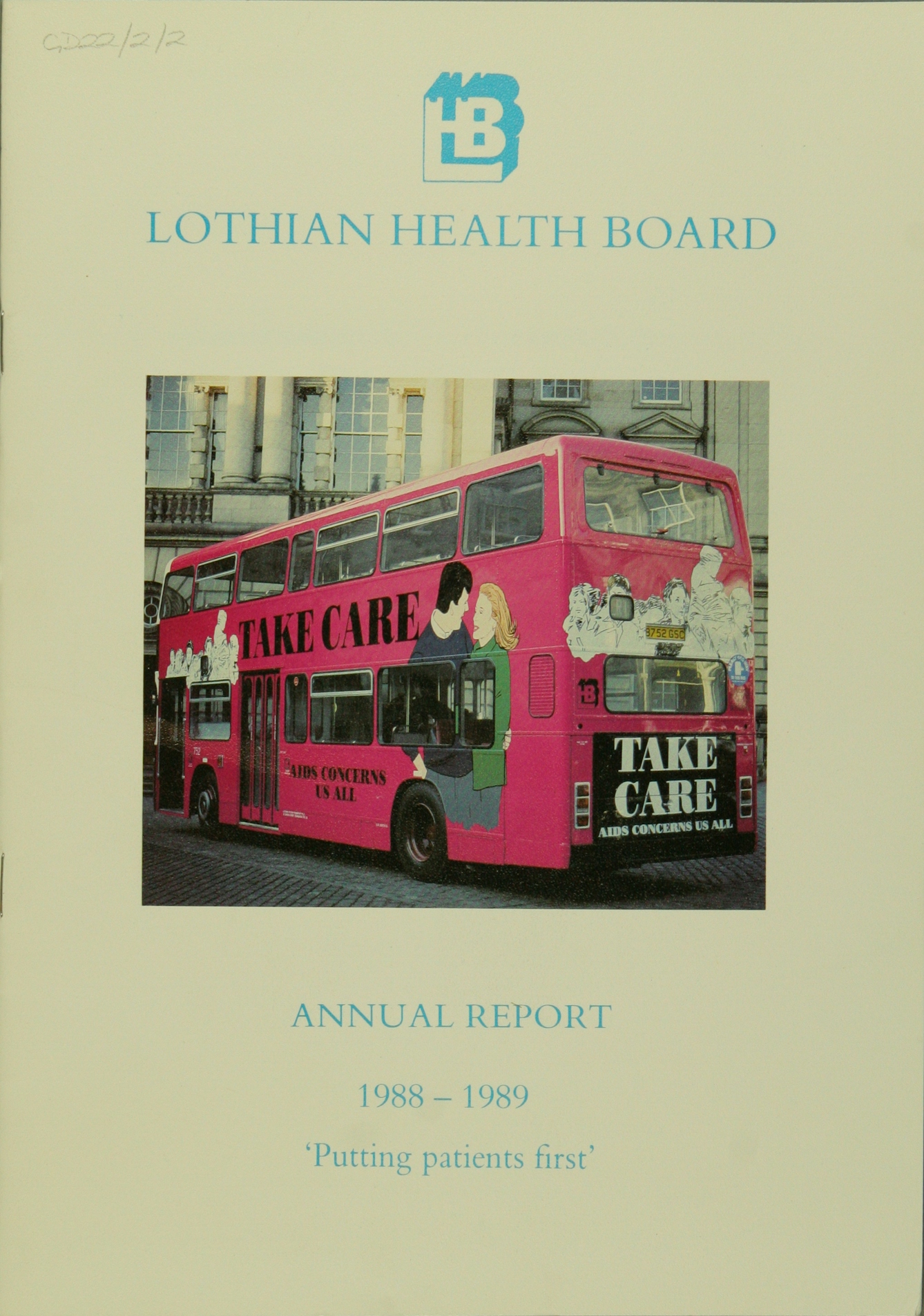

Meanwhile, the Lothian Regional Council teamed up with the Lothian Health Board to develop the ‘Take Care’ campaign. Together they produced an array of health-education materials, such as pamphlets and teaching packs for schools. They even created a bright pink city bus that drove around Edinburgh several years.

The ‘Take Care’ campaign also partnered with rival football teams, Hibernian Football Club and Heart of Midlothian Football Club, to specifically encourage men to “take care” of themselves. Postcards invited football fans to learn about HIV/AIDS. From kilts and comics to city buses and football, the Scottish experience of the AIDS crisis was structured in locally specific and media-specific ways. Nightclubs would never be the same, but neither could the high street or football pitch.

About the author

Colin Moore

Colin Moore is a health history PhD researcher with the University of Strathclyde and University of Edinburgh. He is working on a project called ‘Communicating Prevention’, which examines activism, health education and lived experiences of HIV/AIDS in Scotland during the 1980s and 1990s.