Wellcome’s Adrian Plau shares some of the stories behind the Asian palm-leaf manuscripts in our collections. He reveals how British colonialism impacted this special form of knowledge transmission and the challenges involved in unearthing each manuscript’s origins and how it came to be at Wellcome Collection.

Stories of Asian palm-leaf manuscripts

Words and films by Adrian Plau

- In pictures

Palm-leaf manuscripts are one of humanity’s most ancient and widespread technologies for transmitting and preserving knowledge in written form. They are made from two types of palms: palmyra and talipot, both found in South and Southeast Asia. Palmyra palms have an enormous range of uses, from mats and thatching to hats and fans, in addition to making palm-leaf manuscripts.The talipot palm lives for around 60 years but flowers only once. Death follows soon after its lone blossoming, but the leaves of the tree are cooked and dried and take on a second life. Inscribed with a stylus and rubbed with ink, they become palm-leaf manuscripts.

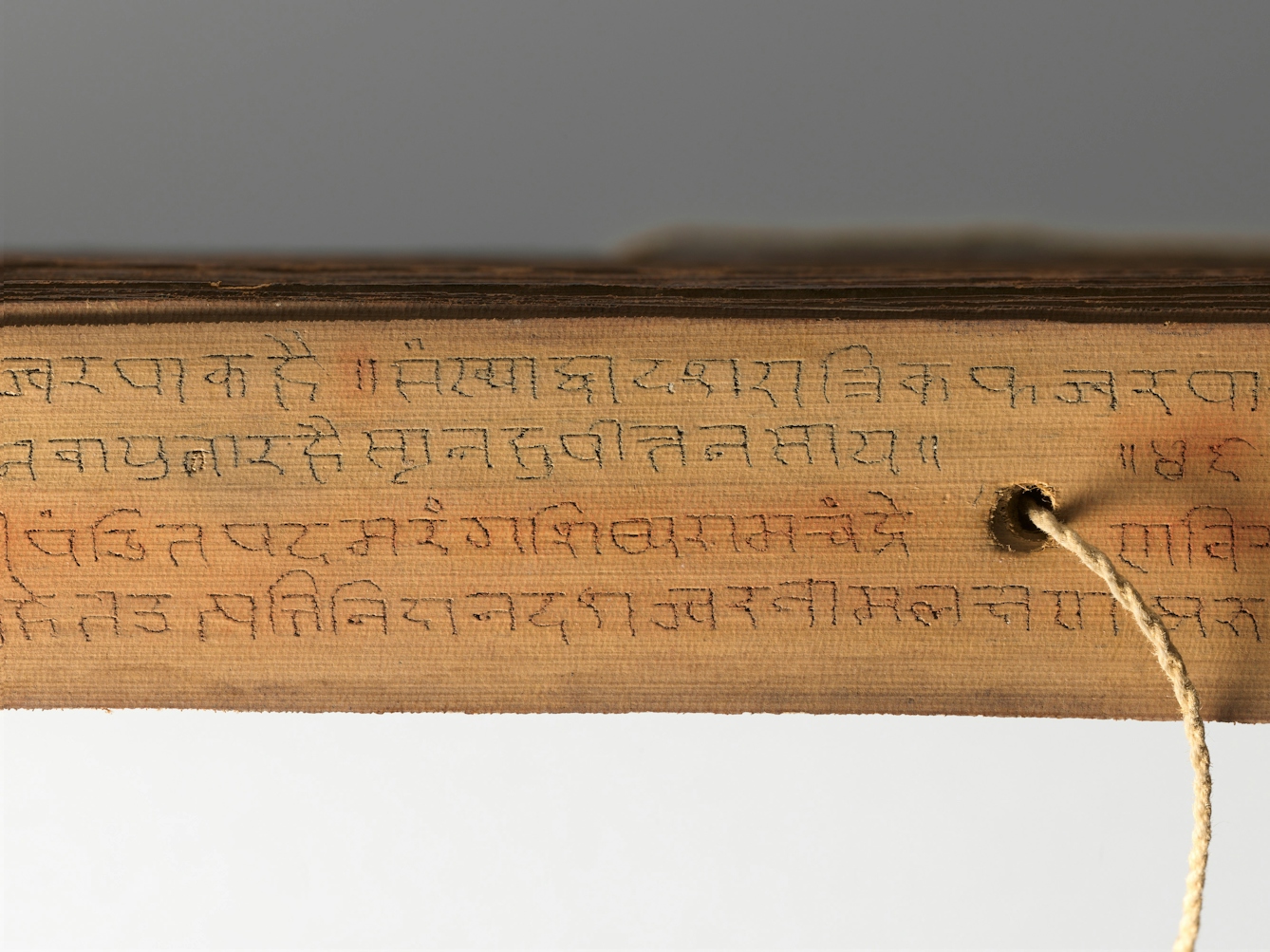

The process of turning palm leaves into manuscripts begins with the seasoning process, which helps prepare the palm leaves for long-term storage. First, branches are cut and completely dried in the sun. The dried and cut leaves are made into a roll tied with string. The rolls are boiled in water along with aloe vera pulp for about an hour to make them stronger. After being straightened and rolled to make them smooth, the leaves are cut into the proper shape and size, and a hole is made in the middle of each leaf to connect them together and make a palm-leaf volume.

Measurement lines are drawn on the leaves as a guide to writing. The writing is done with a pen or brush stylus, by engraving or etching into the surface of the leaf. Dr Kalpana Sheth of Ahmedabad University, who has catalogued thousands of historic manuscripts for Wellcome Collection, notes that, “Writing on dried palm leaf is not easy. It needs proper pressure and technique. Once a mistake is made, it can never be corrected.” Once both sides of the leaf have been inscribed, black colouring is applied to make the incisions more visible. Dr Sheth adds, “Sometimes the palm leaf is preserved and protected from insects by also applying a mixture of turmeric powder, mustard oil, neem powder, and camphor powder.”

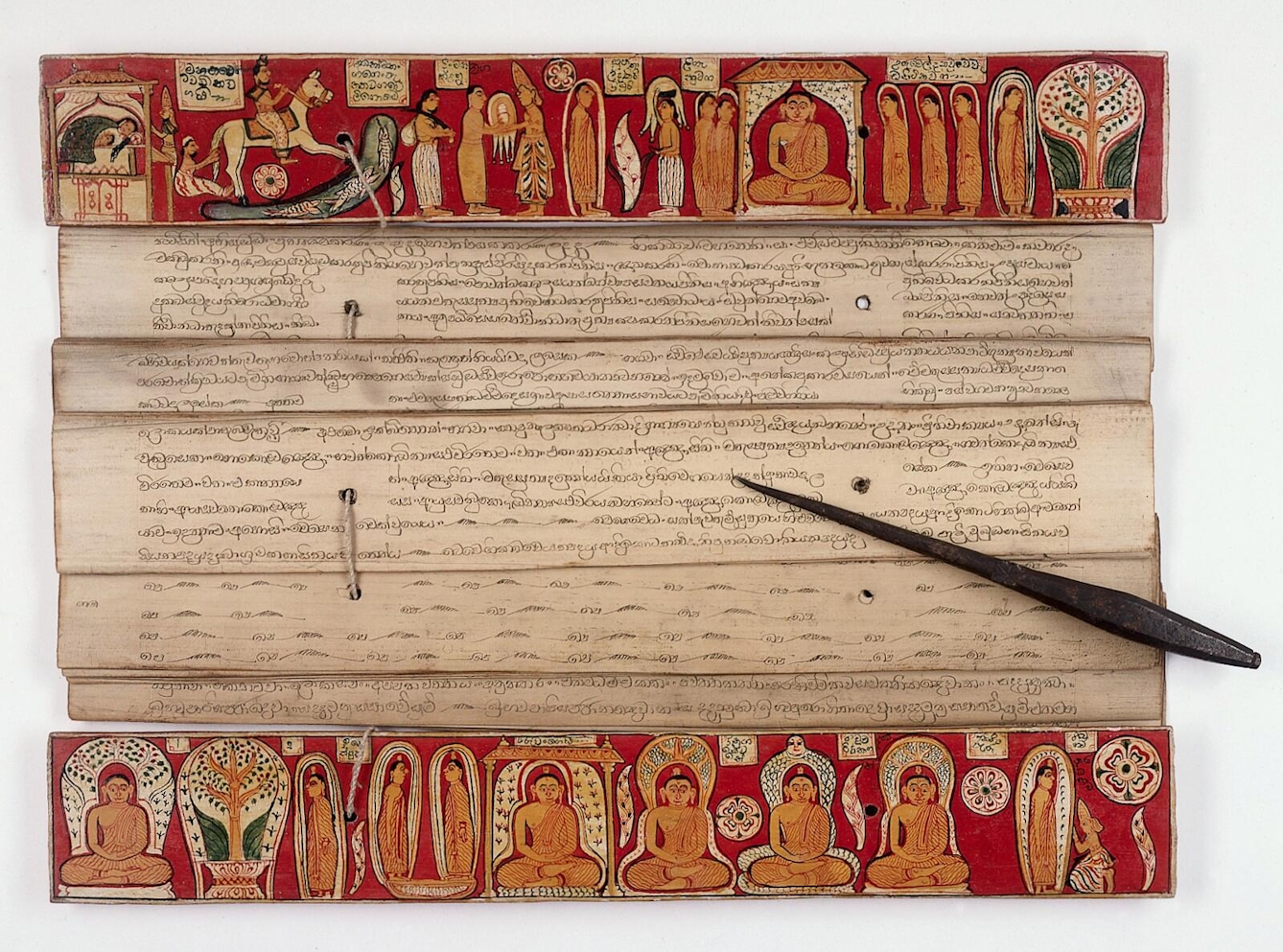

Palm manuscripts displayed in Western museums for their visitors tend to be ancient and lavishly illustrated. For example, this manuscript, labelled prosaically as MS Indic Epsilon 1, is one of the rarest, most valuable items in Wellcome Collection. The manuscript is a copy of the Mahāyāna Buddhist treatise ‘Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra’ (‘A Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses’) and does indeed feature several beautiful illustrations of Bodhisattvas, deities, and episodes from the Buddha’s life. The image shows an incarnation of perfected wisdom in the form of Prajñāpāramitā Devi. The manuscript was purchased by Dr Paira Mall, a Punjab-born physician who acquired many items for Henry Wellcome in India.

Palm-leaf manuscripts offer intriguing clues into how knowledge was disseminated and exchanged over time and through the many languages and kingdoms of South Asia. The scribe who copied Epsilon 1 presents himself as a man named Jivadhara, based in Nalanda (in the modern-day state of Bihar in northern India), the world’s first residential university and one of the ancient world’s prime centres of learning. But the manuscript uses the Bhujimol script used in Nepal, which is not typically found in Nalanda manuscripts from the 11th century.

Scholar Eva Allinger argues that Epsilon 1 dates from the 12th century and was copied in Nepal, not Nalanda. We don’t know who the Nepali scribe was or who might have commissioned and paid for what clearly was an expensive and complicated project. However, it is tempting to speculate that the owner wanted something with the splendour and prestige associated with Nalanda, yet readable Bhujimol. The world of manuscripts is nothing if not full of adaptation.

While the illustrations in Epsilon 1 and similar palm-leaf manuscripts are beautiful, they are spread over 208 leaves, only six of which contain illustrations. Palm manuscripts were not intended for display; most were for more everyday use – the equivalent of paperbacks rather than coffee-table books. Like paperbacks, they come in all shapes and sizes and can be just as rare and valued.

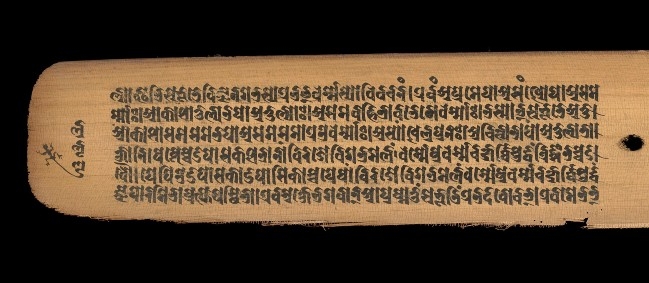

MS Hindi 39.01 is a case in point. It is the only palm-leaf manuscript in Wellcome Collection written in Hindi. Made in 1763, it is a copy of Ramchand’s ‘Ramvinod’(‘Ram’s Pleasures’), an early modern medical treatise that was extremely popular across north India and beyond. This copy was completed about 100 years after Ramchand’s original, finished in 1663.

Palm-leaf manuscripts demonstrate how knowledge was disseminated, adapted and modified through centuries of copying and translating texts such as Ramchand’s medical treatise. They also challenge imperialist notions of a timeless, unchanging South Asia where history began with European colonisation. Far from being timeless, ancient practices such as Ayurveda continued to develop through physicians such as Ramchand and Nainsukh, and the many copies of their works, such as MS Hindi 39.01, that have been made and circulated into modern times.

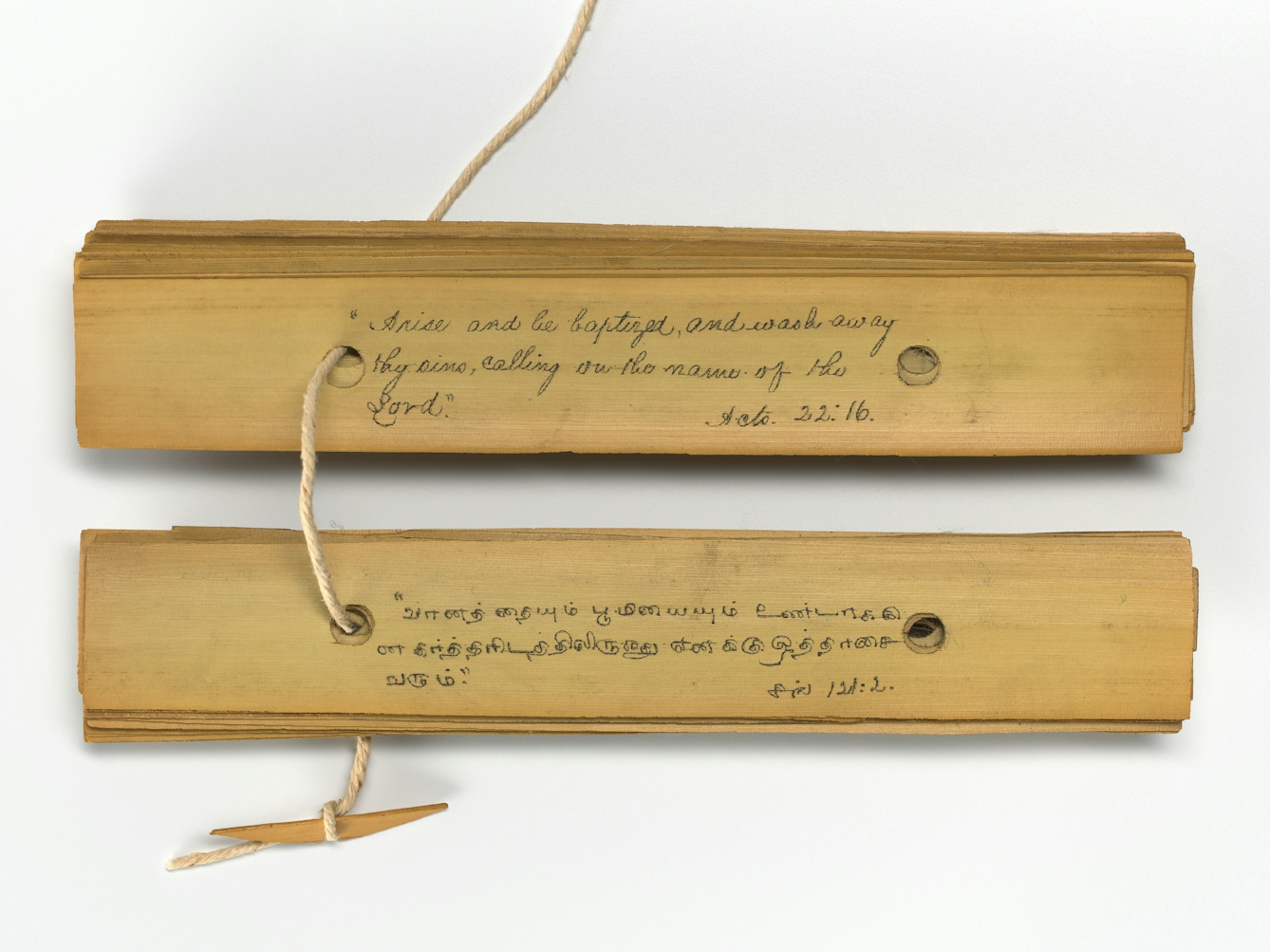

A striking example of how palm-leaf manuscripts were adapted through colonialism is a Tamil manuscript, MS Tamil 3. According to its colophon, the manuscript was made by the scribe M Vethamanikam at the Nagercoil Seminary in the South Indian Kingdom of Travancore. The seminary at Nagercoil (now a city in Tamil Nadu) was established in the early 19th century by British missionaries. MS Tamil 3 contains a range of brief quotations from the Christian Bible, first in Tamil script and then in English translation on the flip side of each leaf. In this, it demonstrates both the continuing tradition of palm-leaf manuscripts, and how such local practices and traditions could be used for colonial purposes.

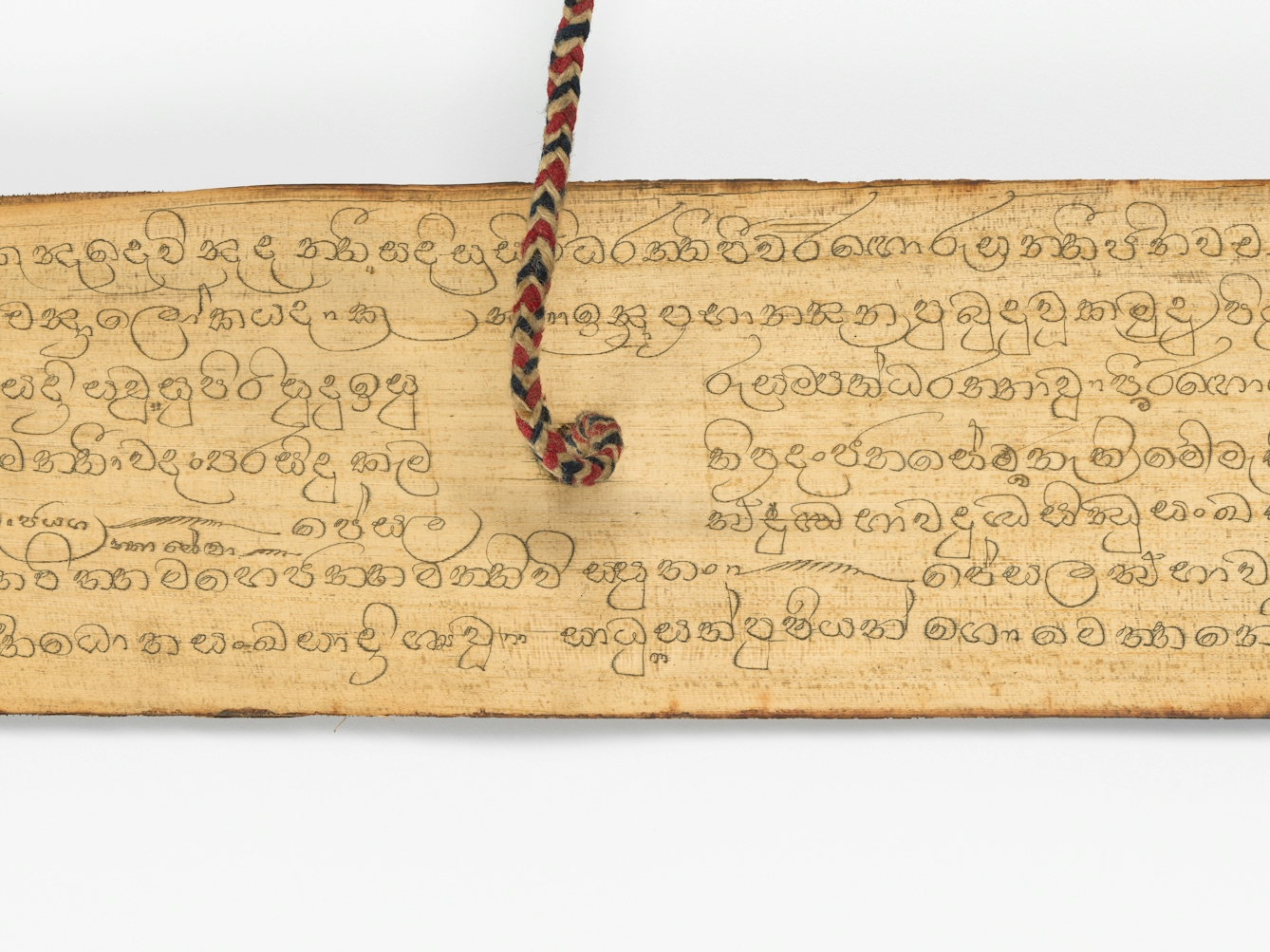

MS Sinhala 91 and MS Sinhala 92 are Sri Lankan manuscripts that give further testament to the imprint of British colonialism on the palm-leaf manuscript tradition. They were created by two Buddhist monks, (signified by the thera honorific in the texts). While both manuscripts use the same eight-line astaka format of praise poetry and feature paraphrases in Sinhala, one is written in Sanskrit and the other in Pali. Both are addressed to Sir John Frederick Dickson (1835–91), who spent 25 years as a British colonial administrator in Sri Lanka. Dickson was fascinated by Buddhism and learned to read Pali. The quite generic phrases suggest that these manuscripts were commissioned by Dickson himself.

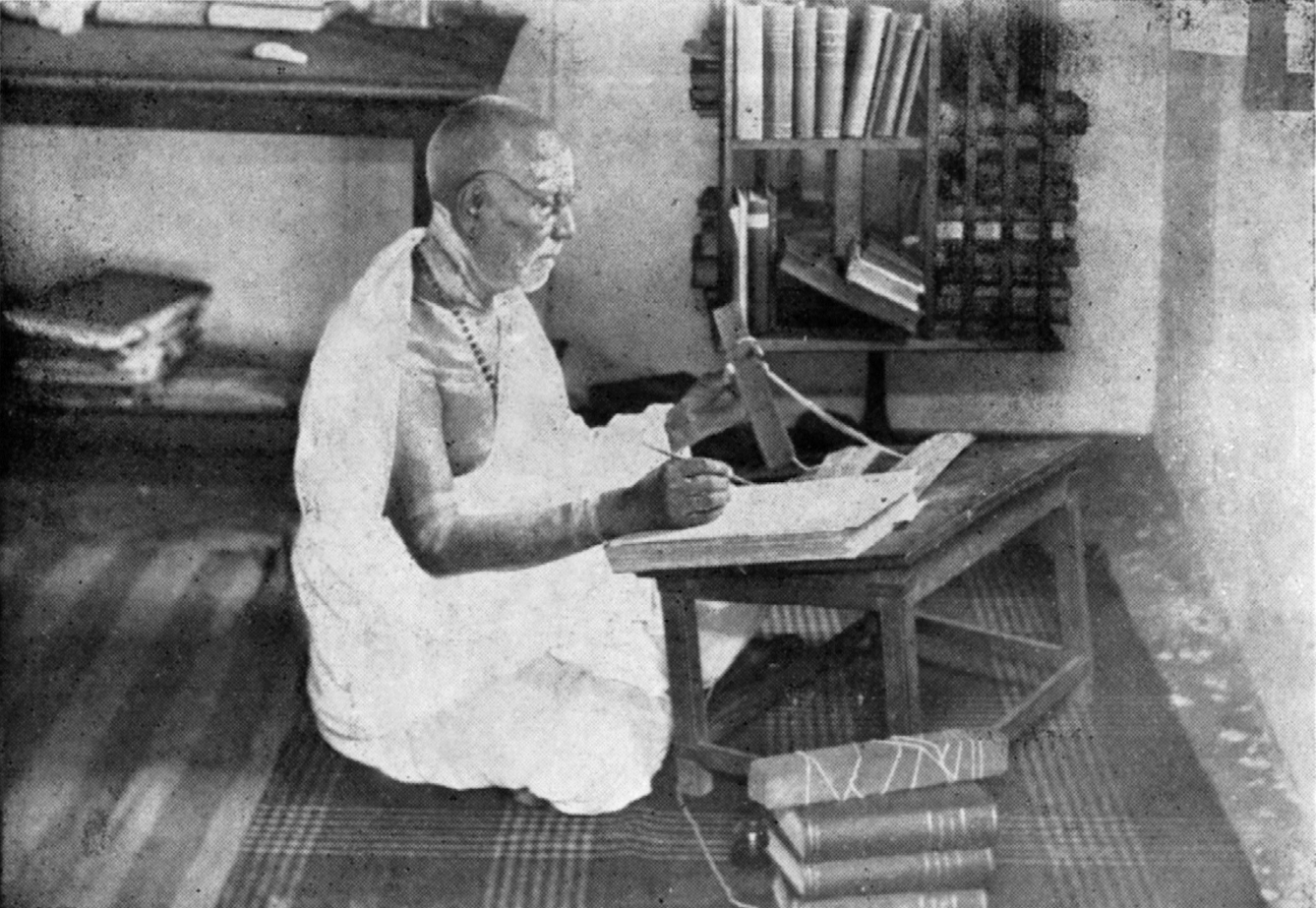

The presence of the palm-leaf manuscripts in Wellcome Collection is itself a tangible imprint of British imperialism across Asia. Collectors such as Henry Wellcome had the wealth and privilege to buy more or less everything they wanted to acquire, and the global inequalities of colonial rule enabled them to do so. We are working to retrace the stories of how these items came into the collection, but this is by no means a straightforward task. For example, of the 11 Javanese manuscripts in the collection,we know that six were bought at auction in London between 1916 and 1934, but so far, we do not know how the other five came to Wellcome. And in the process of conducting an inventory of all our manuscript collections, we’ve found a 12th, uncatalogued Javanese manuscript.

By conducting this inventory, researching the histories of the items (this is just a small sample of the historical acquisition records at Wellcome Collection), and updating our cataloguing information, we strive to make it easier to find and access the manuscripts in our collections. Where possible, we are also working to digitise and transcribe manuscripts to make them more widely accessible to audiences around the world. Revealing the stories behind objects in Wellcome Collection and how they came to be in the collections is going to be a long process, but we’ve taken the first steps.

About the author

Adrian Plau

Adrian Plau is Manuscript Collections Information Analyst at Wellcome Collection, and a recent Headley Fellow with the Art Fund. He holds a PhD in South Asia Studies from SOAS.