Precious stones and crystals have been used for healing and protection in different cultures around the world for hundreds of years. Art historian Louisa McKenzie reveals the stories behind some notable examples.

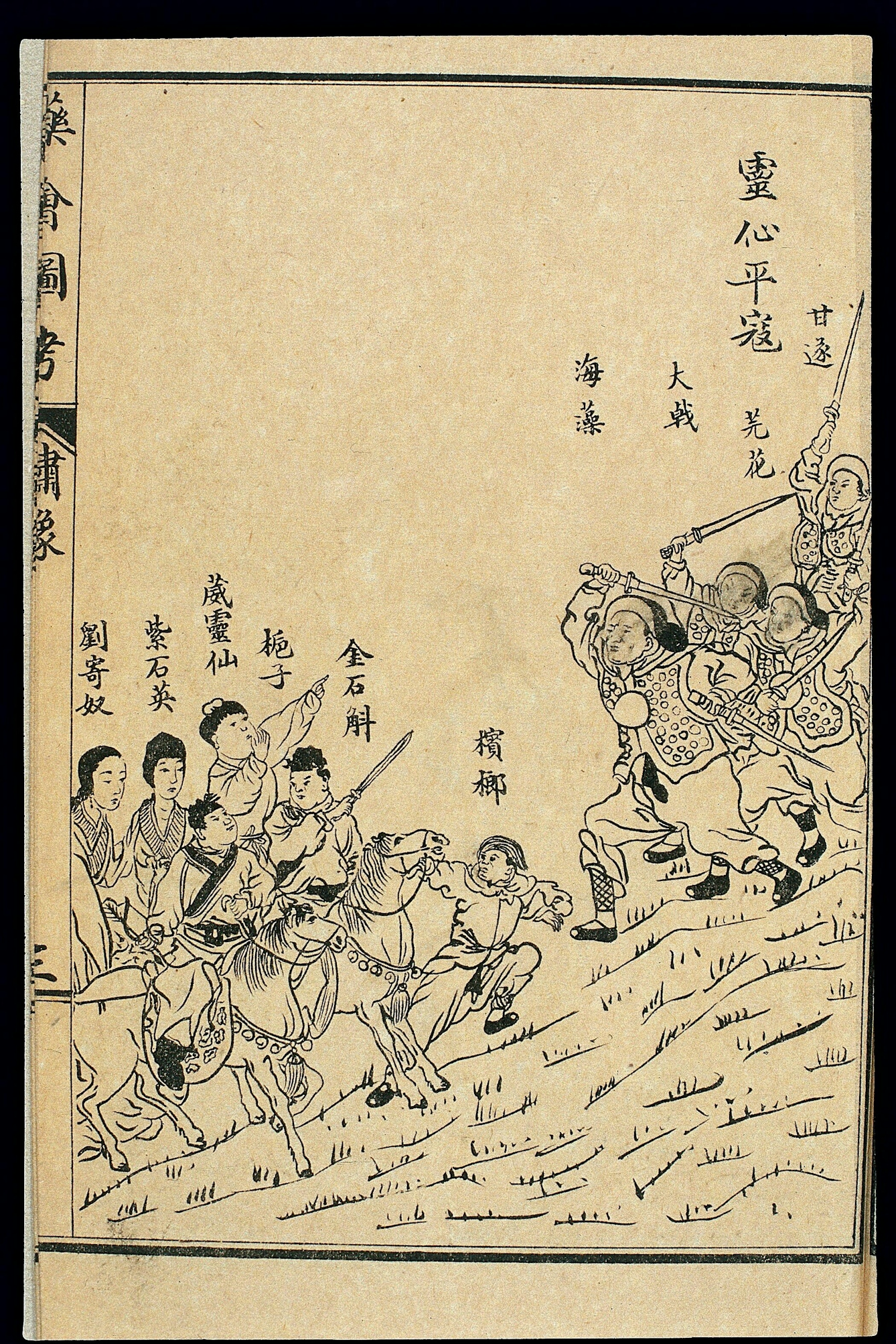

Semi-precious stones have been deployed by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners for thousands of years to treat and manage a variety of ailments. This image is one of ten scenes from the ‘Yaohui tukao’ (‘Illustrated Congregation of Drugs’) that personify various Materia medica (substances used for healing) as protagonists in a battle. Alongside representations of several plants is the semi-precious stone amethyst (zishiying), which is believed to have calming properties and to settle the heart.

Crystals and precious stones were used in Ancient Egypt to fashion amulets such as this one. The translucent heart is made from rock crystal, with the face in carnelian and the hair in black soapstone. The healing sought from these amulets could be spiritual as well as physical. In Ancient Egypt, the heart was believed to house an individual’s soul and memory. Thus, an amulet such as this, in the shape of a heart, was designed to guard the individual’s intellect and was an important part of the ritual transition from life to afterlife.

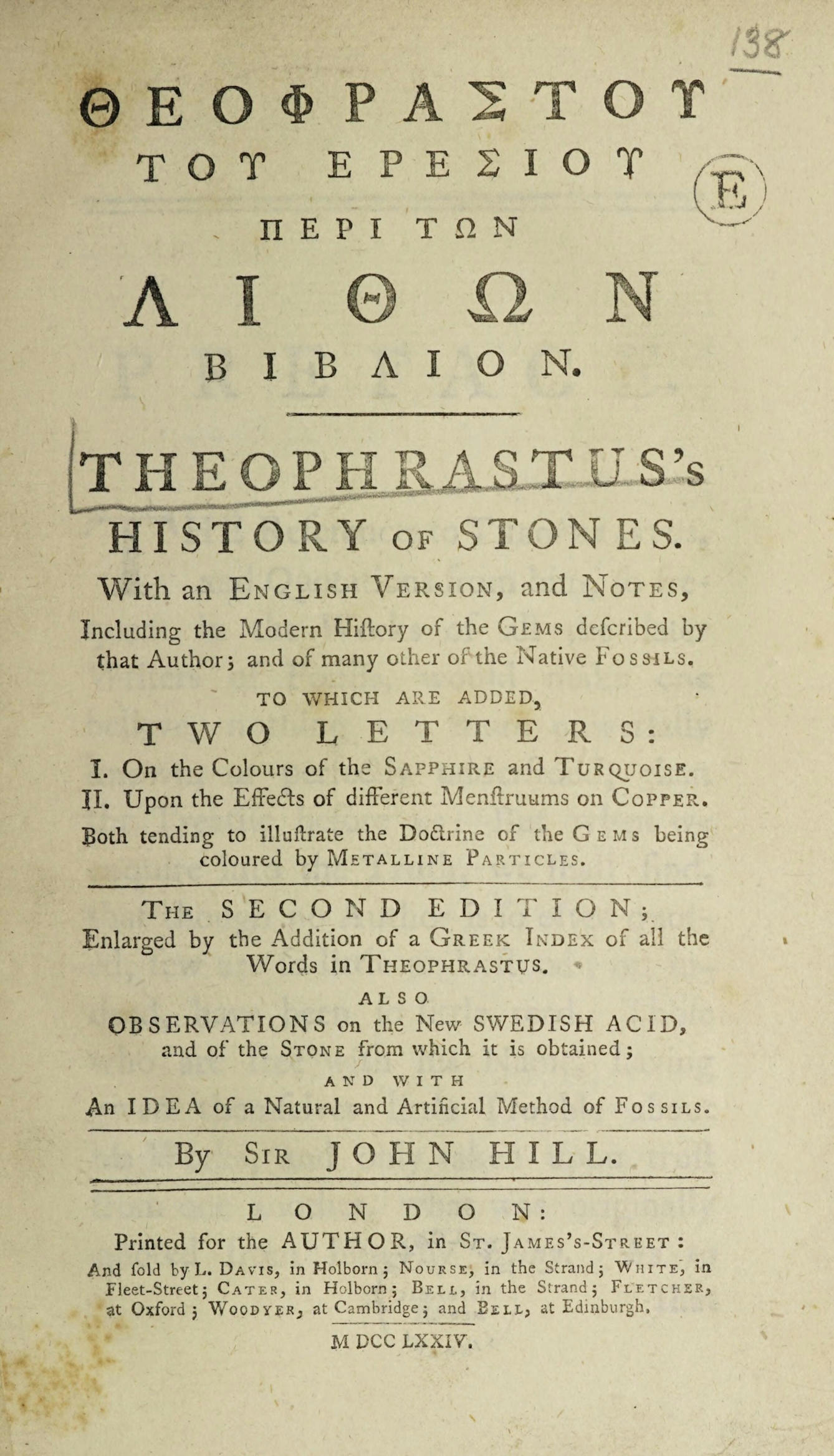

An Ancient Greek philosopher, Theophrastus, wrote the treatise ‘On Stones’ in the third century BCE. The work was first translated into Latin in the 15th century and remained a key reference text for those interested in using precious and semi-precious stones during the Renaissance and beyond. Theophrastus assessed stones by their behaviour when heated. According to an 18th-century English translation of ‘On Stones’, emeralds were particularly prized for their healing properties in ancient times. In powder form they guarded against poisoning, gastrointestinal problems, haemorrhages and plague. As an amulet they protected against – among other things – epilepsy and helped with childbirth.

Lapidaries were popular texts in the Middle Ages, listing different stones and their various properties and uses, including how they might help an individual avoid specific diseases or other types of misfortune. The ‘Book of Secrets of Albertus Magnus’ advises wearing a diamond bound on the left-hand side of the body to discourage enemies, both tangible (humans and wild or venomous beasts) and intangible (“madness” and hallucinations). The 12th-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen included a section on stones in her encyclopaedic text ‘Physica’ (Book IV). This discussed the medicinal properties of stones and the charms made from them. Sapphires, which would also have been stored in this much later pharmacy jar, were particularly prized for helping with eye issues.

Goa stones were composites designed to mimic the bezoar stones found in the stomachs of ruminant animals. Principally manufactured in Goa, India by Jesuit missionaries, these objects were valuable exports in the 17th and 18th centuries. Made from a variety of items, such as bezoar itself, resin, musk and crushed precious gems, these stones were designed to be scraped and the resultant powder mixed with water or tea and drunk. They were believed to cure any number of medical conditions, including the plague. Goa stones were often kept in elaborately designed silver or gold caskets.

The use of stones as talismans (objects believed to protect someone from illness or misfortune) was not confined to the distant past. The example at the top of the picture, made from agate, was produced in Devon in the UK in the first decade of the 20th century and used by fishermen to protect against the “evil eye”, a malevolent curse or intention. The way the stone looked was as significant as its internal properties. This banded agate resembles the iris of an eye – strengthening the potency ascribed to it in protecting against harmful glances.

Although coral comes from a marine invertebrate and is thus not a mineral, it was classified as a stone until the early modern period. Prized for its protective powers in the medieval and Renaissance periods, it was often used in teething rings for aristocratic children. Mano figa (or fica) charms are frequently made from coral and are still popular in Italy. The mano figa charms in this image depict the characteristic gesture with the thumb between the index and second fingers, which was also meant to ward off the “evil eye”.

John Dee was a Renaissance polymath and an adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. His many interests included mathematics, astrology and divination. Dee claimed that this quartz crystal mounted in metal was given to him in 1582 by an angel, Uriel. Dee used it in his attempts at scrying – or predicting the future using a reflective object like a crystal ball. This particular crystal was later passed, via Dee’s son, to the physician Nicholas Culpeper, who used it to treat illnesses. Although the crystal cured his patients, by Culpeper’s account, it seemed to draw its healing energy from his own person. This left him weak and susceptible to “demonic temptation”, which prompted him to stop using the crystal in 1651.

The late 20th century saw a resurgence in the use of semi-precious stones, especially in crystalline form, for healing in alternative medicine. In contemporary crystal healing, some people believe that crystals such as quartz and amethyst promote the flow of good energy and help rid the body and mind of negative energy, with physical and emotional benefits. Sometimes this belief is linked to traditional systems of healing, such as acupuncture, chakras and yoga. The crystals are worn as jewellery, used in meditation, placed on specific parts of the body, or infused in water. Although crystal healing through energy flow has been dismissed as pseudoscience by conventional medicine, it has undoubtedly become big business.

About the author

Louisa McKenzie

Louisa McKenzie has a PhD in art history from the Warburg Institute. Her thesis, funded by a London Arts and Humanities Partnership (AHRC) Studentship, considered the economic and devotional lifecycles of wax ex-votos in Florence 1300–1500. She researches the art and material culture of late medieval and early Renaissance Florence.