Yaw Afrim Gyebi embarks on a journey from his home in Accra, Ghana, tracing the kola nut’s path from farm to market. Eventually arriving in Boayini, Yaw explores the crucial role that kola nut plays in the lives of the people who grow, sell and use it.

Nothing without kola

Words and photography by Yaw Afrim Gyebiwords by Vanesha Kirita Singhaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Photo story

The journey of a kola nut begins with the farmers who cultivate it in the fertile lands of Bechem, Bono Ahafo, in the south of Ghana. One such farmer is Acheampong Prince, who started cultivating kola nuts as a teenager under the guidance of his mother and late father.

The kola nut’s versatility has made it a valuable crop for the family. It thrives in both dry and rainy seasons, and is popular for its many health benefits.

The kola-nut tree is also ecologically important. It acts as a protective canopy for other crops like cocoa and cashew, which is why most cocoa farmers have incorporated kola trees into their farms. “Every cocoa farmer had a couple of kola-nut plants mixed with their cocoa trees,” Acheampong says.

Acheampong Prince on his plantation with a fresh harvest of kola nuts.

However, kola-nut farming has not been without challenges. In 1983, Ghana faced severe wildfires as a result of climate change, devastating farms across the country. These fires destroyed countless kola-nut plantations, contributing to a great famine that year. Acheampong recalls the profound loss this caused for his family and other farmers.

But today, he has hope. Acheampong has recently learned that kola nuts are also used to make tie-dye fabrics. He’s decided to clear a portion of his land to start a kola-nut nursery, with a renewed focus on cultivating kola nuts as a primary crop, rather than just using them to support other types of produce.

Portraits of Mary Acheampong, who cultivates coffee, pepper and other crops, and Ashietu Seidu, who started the farm with her late husband and provides invaluable support.

Farming families in the region are resilient. In fact, family is vital in sustaining agricultural livelihoods and traditions. Acheampong’s mother, Ashietu Seidu, is a pillar of support on the farm, while Mary, who is married to Prince Acheampong, cultivates coffee, pepper and other crops.

Trade and tradition

For many families in northern Ghana, kola nuts provide an important source of income.

After harvest, kola nuts are transported to bustling markets, like this one in Langbinsi, Northern Ghana.

Kola nuts being arranged and sold in the market.

Traders – many of whom are women – carefully sort the nuts by colour, size and quality, and engage in lively exchanges.

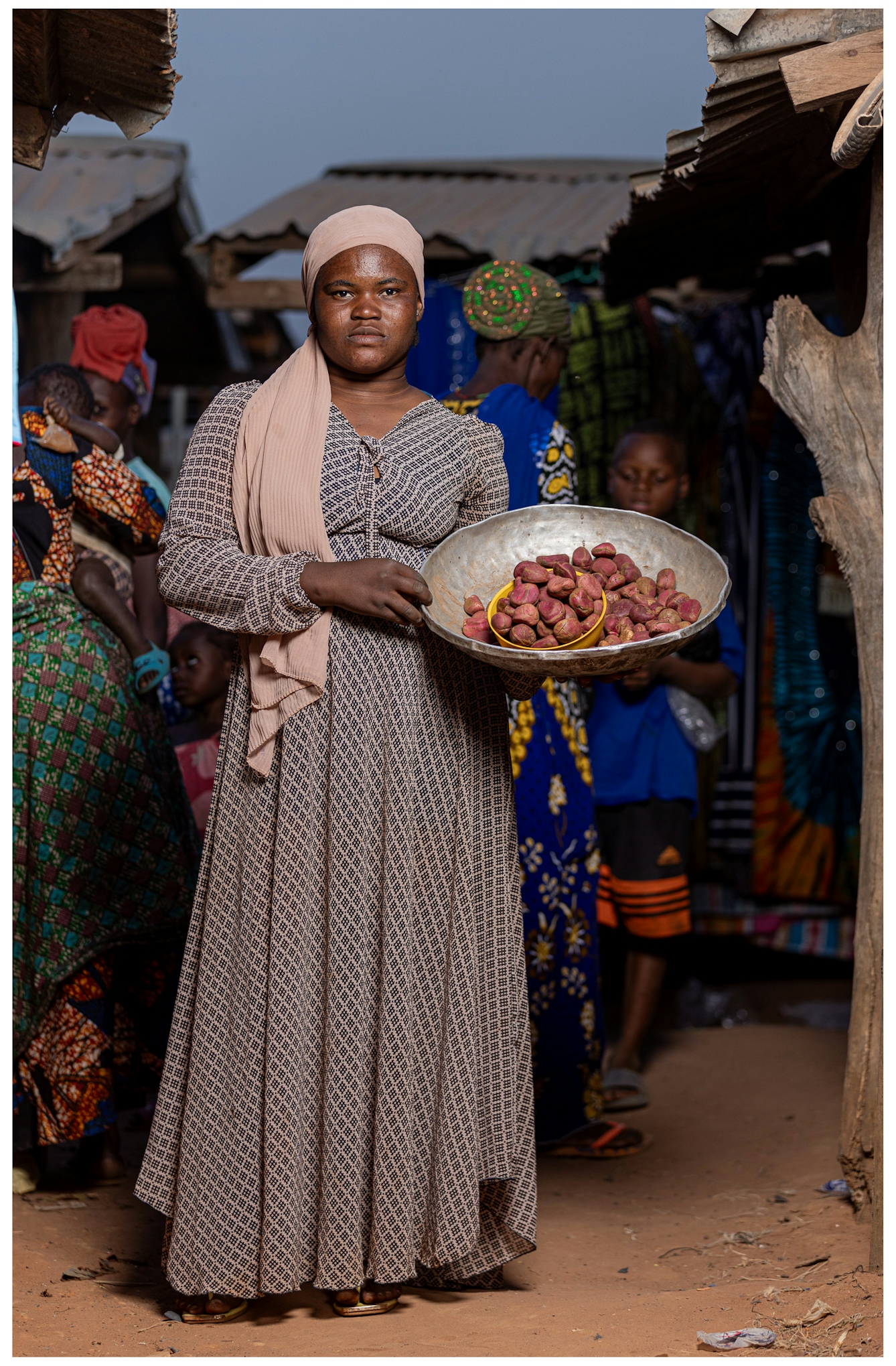

A young woman sells kola nuts in the market.

Kola nuts, alongside other crops, serve as an important source of income for many families.

In ancient times, kola nuts were used as a type of currency in Northern Ghana, similar to a coin or a cowrie (a small shiny shell that was used as money in the past in parts of Africa and Asia). They were essential for purchasing land and property, and were presented as gifts on important occasions, like visiting elders.

Kola nuts are still given today as a gesture to inspire action and motivate the recipient.

A man sells kola nuts in the lively market.

The protective powers of kola nut

The community of Boayini is nestled in Northern Ghana’s Walewale district. Here the kola nut (known as ‘gori’ in Mampruli) is a cornerstone of tradition, healthcare and daily life.

It’s believed to have protective powers for spiritual and mental health too.

Many people think chewing kola nuts before leaving home wards off bad luck or misfortune. It gives them confidence to navigate the challenges of daily life.

Photos of Abiba Duut, who is 115 years old, with her son. Abiba says that kola nuts once prevented her from being attacked by spirits.

Abiba Duut is 115 years old. In her early teens, Abiba says she encountered two spirits who were twins. She explains that only she could see them, which made the spirits anxious. They then attacked her, leaving marks on her arm.

Abiba says that a local spiritualist advised her to always carry kola nut to prevent the spirits from attacking her again.

Ceremonies and rituals

In Boayini, kola nuts are offered as a sign of respect. At weddings, for instance, kola nuts are presented to both families who take a symbolic bite of unity and acceptance, similar to how Tani Tia is in the portrait below.

They are also important at funerals and are given to people tasked with burying the deceased; the gesture is believed to bring peace to the spirit of the departed and harmony to the living.

Portrait of Tani Tia consuming a kola nut.

An important part of any ritual is purifying the kola nuts: cleanliness is key, so they are washed properly before consumption.

Kola nuts are washed before ceremonies. They're stored in traditional pots with sand and water.

Traditional pots are used for storing kola nuts. They can be preserved with sand and water. The ones pictured here have been preserved in the chief’s banquet hall for extended periods. It is ceremoniously brought out during traditional gatherings.

Resolving conflict with kola

Lanbon Kwabena, Chief of Boayini, consumes a kola nut.

This is a portrait of Lanbon Kwabena, the Chief of Boayini, as he sits in his palace consuming kola nut. He is dressed in a smock referred to locally as ‘fugu’, and there is traditional kente cloth in the background.

Elders of Boayini sit together and share kola nuts. Yakubu Gumah is a revered elder adorned in full regalia.

Elders gather in the chief’s palace to share kola nut and converse. The portrait on the right is of a revered elder called Yakubu Gumah. He is adorned in full regalia with his hat straightened upwards – a distinctive style reserved for occasions involving the chief.

One such occasion is when there is conflict: the community chief will mediate disputes by breaking a kola nut and sharing it among the disputing parties.

This is a dispute settlement between two elders. Kola nut is shared among community members in the presence of the chief. The spirit of sharing fosters a sense of togetherness, which in turn helps the community reach a mutual understanding and reconciliation. This is a simple yet profound act and is central to their cultural practices.

Kola nut is shared among the people in the presence of the chief as a symbol of respect and togetherness.

From the north to the south of Ghana, and across the African continent, kola nuts are consumed daily and are also woven into social and spiritual practices. They are a central part of life for people. This is reflected in a well-known Ghanaian saying: "Everything with kola nut, nothing without kola nut.”

About the authors

Yaw Afrim Gyebi

Yaw Afrim Gyebi, also known as YAG, is a Ghanaian documentary photographer and visual storyteller based in Accra, and specialises in humanitarian, environmental and social justice issues. His work focuses on themes of cultural heritage, community resilience, and amplifying the voices of marginalised groups.

Vanesha Kirita Singh

Vanesha is a digital editor at Wellcome Collection and is interested in bringing different social, cultural, historical and personal perspectives to conversations about health. She has a career in research, curation and editing. Among a wide range of topics, Vanesha writes about Caribbean history, legacies of the Indian indentureship system and resistance to global systems of oppression.