The milkmaid who once extracted milk from the cow and prepared dairy products for the wider community had a mixed reputation. Robust, practical, pretty and pure, she was a symbol of wholesomeness and romantic pastoral innocence. But notions of milkmaids’ purity became tinged with corruption over time, through the sexualised commodification of their image, souring the milk they delivered. Julia Nurse explores their contradictory image.

Milkmaids and the image of purity

Words by Julia Nurse

- In pictures

The contradictory connotations around milkmaids proved an enduring source of inspiration for many artists, whose depiction of their subject was shaped by the changing trends in art.

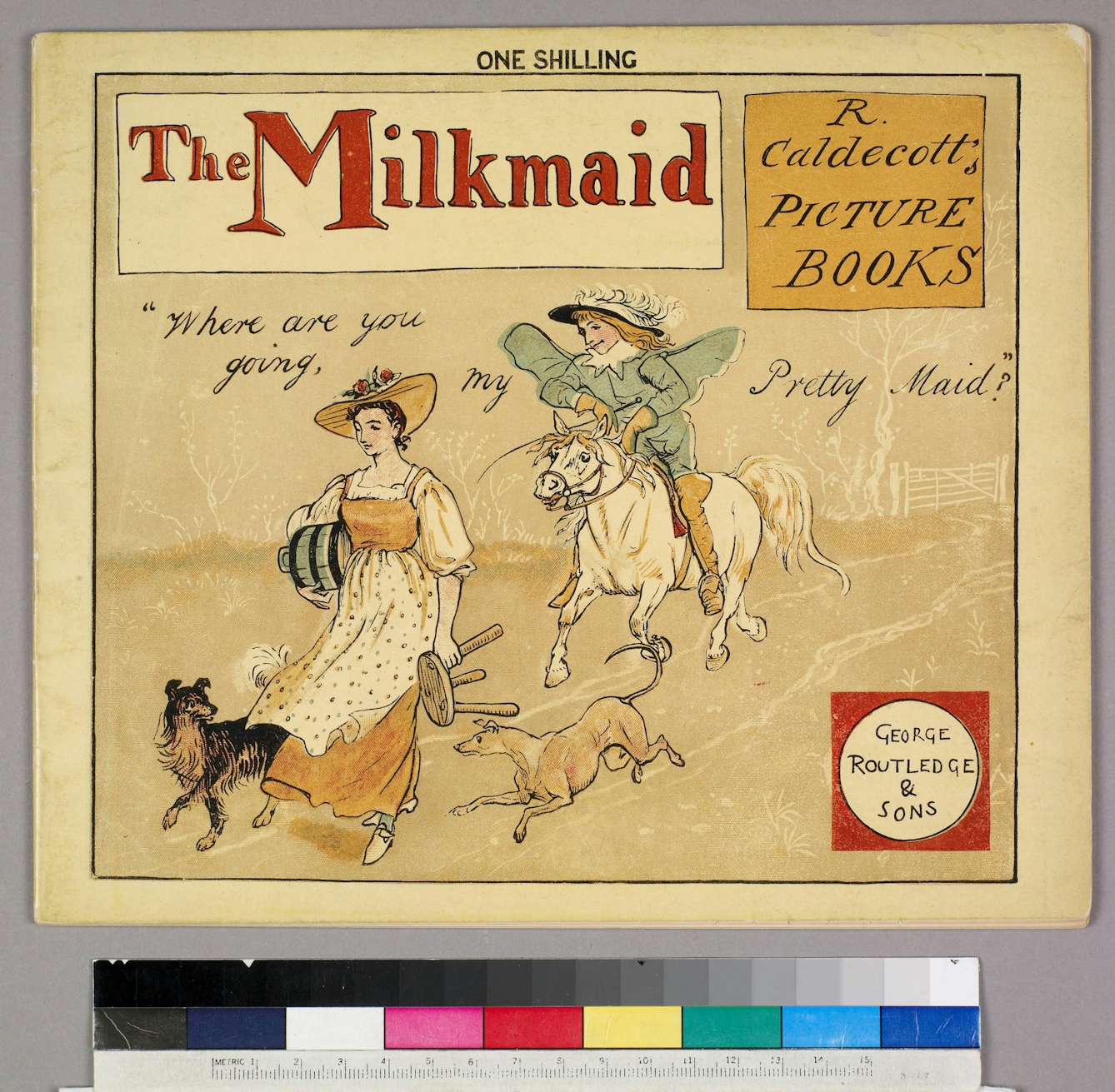

The purity of the imagined rural idyll of the milkmaid was manifested through simple nursery rhymes that evolved from earlier songs suggestive of romantic encounters between a milkmaid and a suitor.

Carrying heavy, milk-laden pails was an arduous and physical task requiring great strength and stamina. Not surprisingly, some representations of milkmaids depicted robust women going about their daily dairy tasks, as popularised in Vermeer’s popular portrait entitled ‘Milkmaid’ and this late 19th-century print.

Milkmaids played up their wholesomeness and beauty to help boost their trade and entice donations from the wealthy elite. To mark May Day in English towns from the 17th to 19th centuries, milkmaids dressed up in borrowed finery and danced in front of their customers’ houses to music, bearing a garland representing their trade. This was evidently a popular event in the calendar, according to this depiction by Francis Hayman at the V&A, originally one of 50 supper-box pictures at Vauxhall Gardens in the 18th century. Even the Royal Family witnessed the dance.

The correlation between the simple life and natural beauty that the milkmaid came to represent meant pastoral portraits were popular among the titled upper classes. The Duchess of Queensbury chose to pose for her portrait in plain dress for this reason.

Notions of the rustic simplicity and youthful beauty of milkmaids is accentuated in this portrait of the vaccine pioneer Edward Jenner, in which a maid can be seen going about her milking duties in the fields. Though it’s been contested that Jenner’s experiments with smallpox vaccines stem from overhearing a milkmaid’s account of how contracting cowpox meant she was immune to the disease, he did take matter from cowpox lesions from milkmaid Sarah Nelmes. The inclusion of a milkmaid in his portrait provided reassurance about the safety of his vaccines and contrasts with images showing people transforming into cow-monsters.

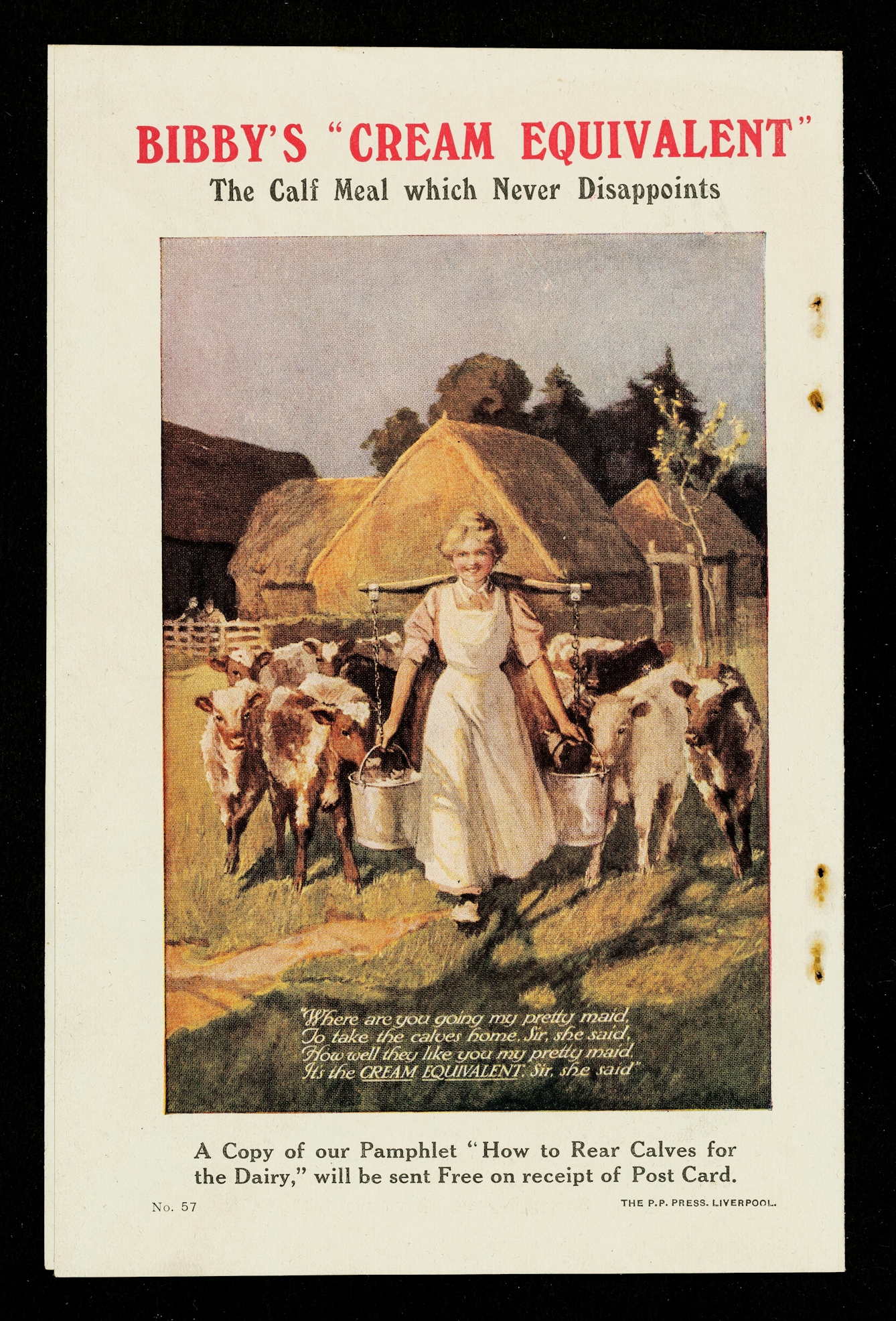

The image of the clean and wholesome milkmaid continued to percolate, helping to sell processed dairy products too. In this advert for ‘Bibby’s Cream Equivalent’, the maid beams at the viewer as her calves gather round her. If we can trust the maids, so too can the cows.

The purity and freshness of milk was often equated with that of the maid’s virtue. Contrasts between virile country sexuality and debilitated urban types persisted across time in literature and art. According to this print by Hogarth, in 18th-century London, milkmaids were not afraid to challenge their customers and actively plied their trade to survive. The milkmaid’s honesty and wholesomeness contrast with the depravity and corruption of the rogue at the centre of the scene.

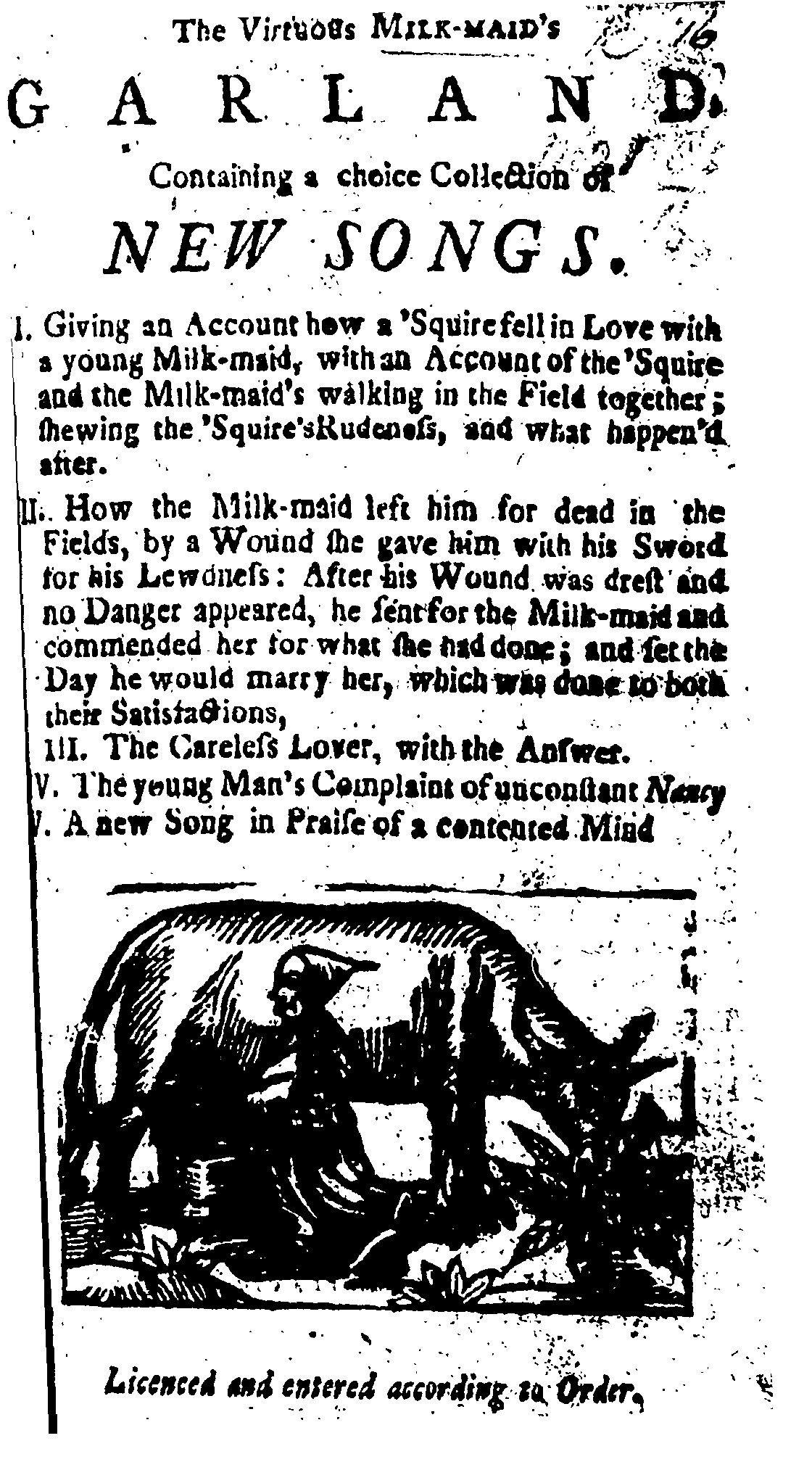

Milkmaids and milk were subject to corruption, though. In ‘The Virtuous Milk-maid's Garland’ a chaste milkmaid avenges the lewd advances of the squire, but she marries him in the end anyway. Set to the same tune, ‘Keep a good tongue in your head...’ implies that the milkmaid’s silence was necessary to maintain respectability. ‘The Sour Milk Garland’ reminds audiences that milk’s freshness was short-lived – the reason for contamination in the context of this song is because the milkmaid is with child.

This advert for Nestlé’s product La Lechera also plays on the idea of how easy it is to taint purity, both biologically and sexually. The text stresses the importance of the quality of the milk used in the product, while the illustration suggests the virtue of the flirtatious maid is easily tainted.

Moralists, eugenicists and reformers worried about immorality and promiscuity among rural labourers like milkmaids, and were concerned about overpopulation by ignorant country bumpkins.

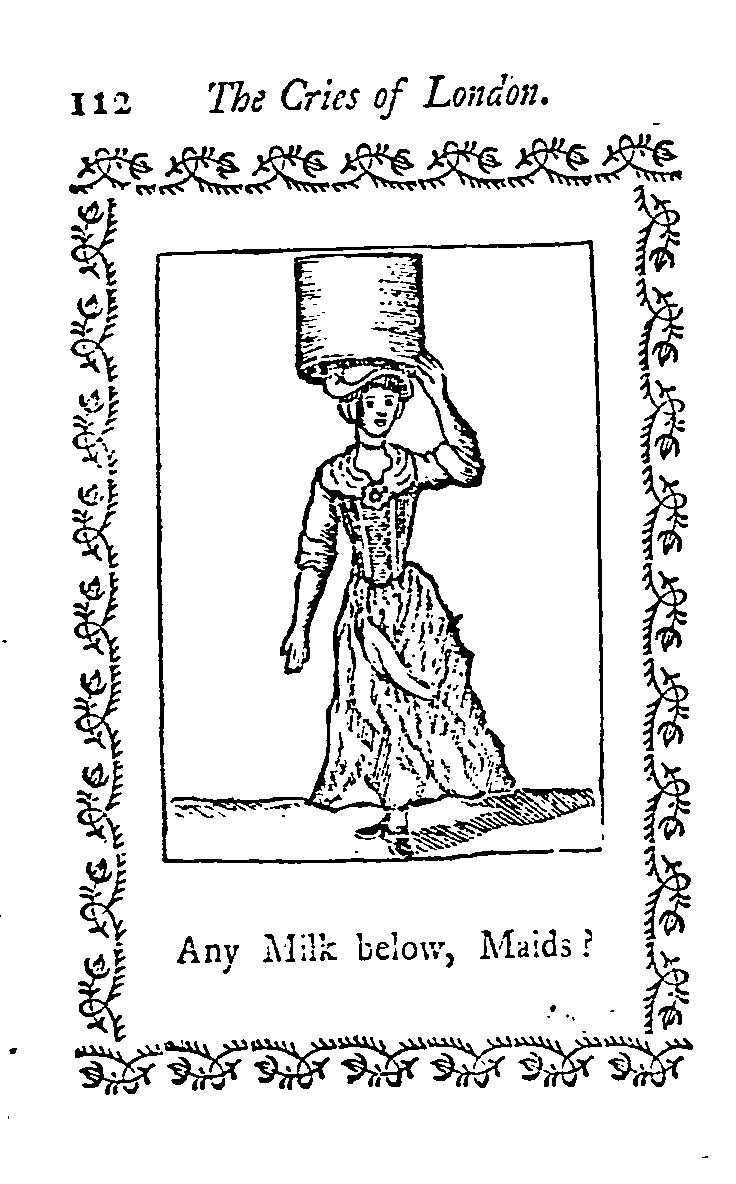

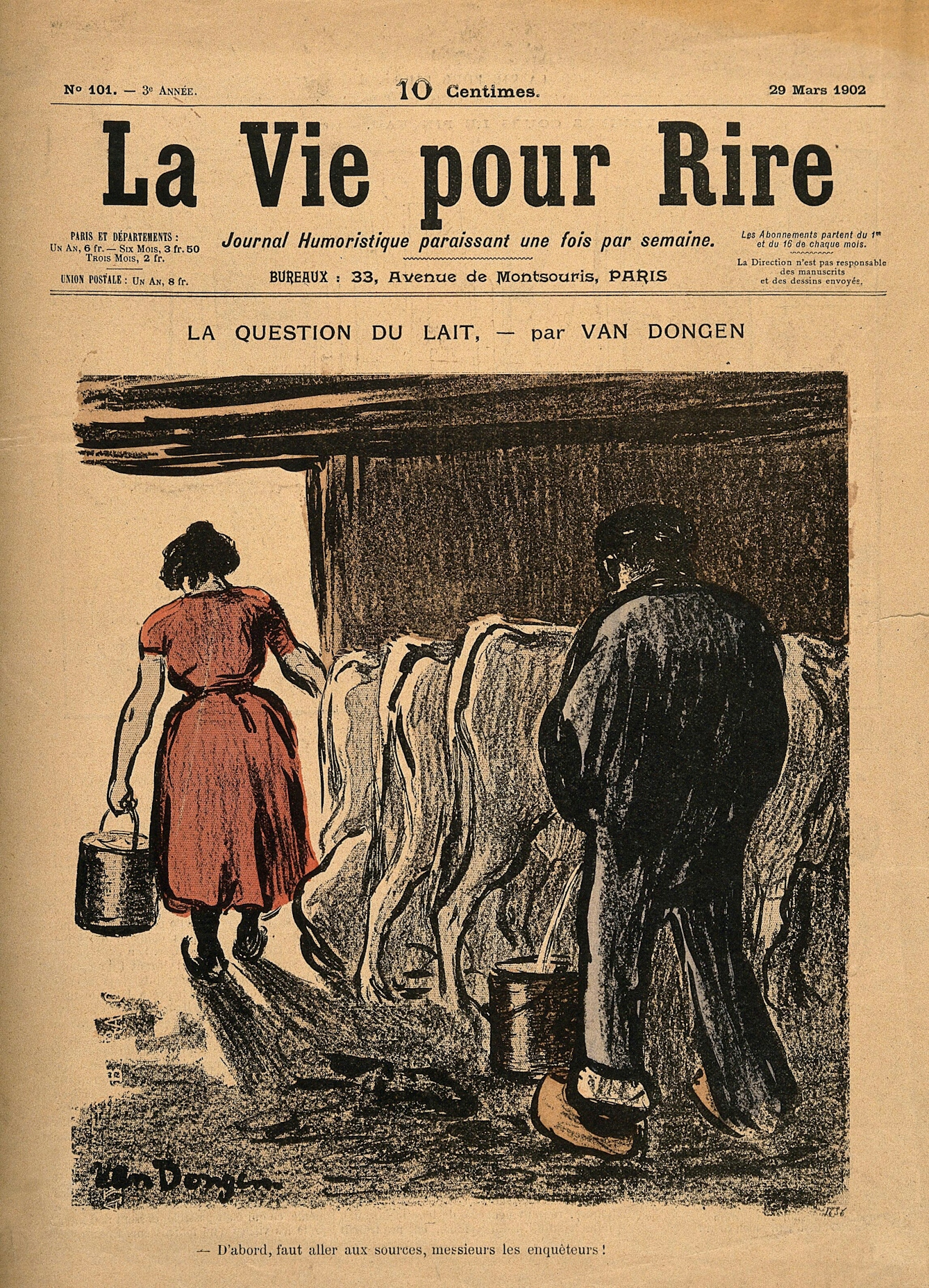

Milkmaids were not even all rural, let alone pure. Images of urban milkmaids were popularised in prints by George Scharf and William Marshall Craig, who included them in his series the ‘London Cries’. These superficially charming prints revealed the stark reality of the lives of the dispossessed and outcast poor, who had to live on the streets as hawkers to survive. Craig’s accompanying text to this series of prints reveals that the milk was often adulterated and that Welsh girls were particularly suited to the task of carrying it around the streets, owing to their “hardiness of constitution”.

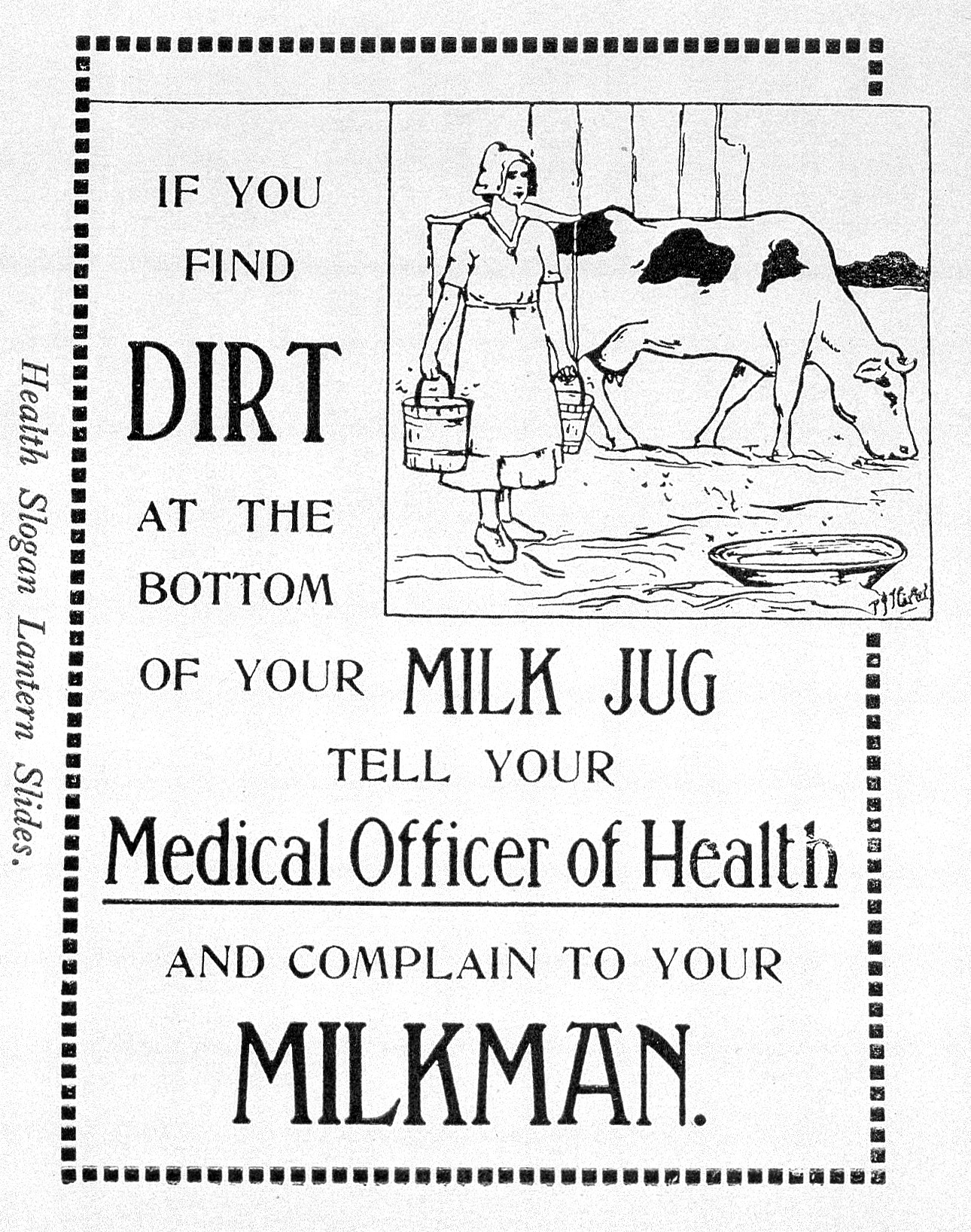

‘Dirty’ urban milk and the women involved in its production continued to be a subject of concern into the 20th century, as shown in this warning from the Central Council for Education from the 1920s.

The transition from “cleanly milkmaid”-produced milk to “farm hand” in the Edwardian period prompted romanticised nostalgia for the disappearing rural labouring life. This image suggests the maid is powerless to prevent unhygienic practices among farm labourers, and is echoed in this Medical Officer of Health Report.

By the mid-20th century, the image of the milkmaid found its way onto a range of products, including cigarette cards, chocolate and biscuit boxes, far removed from the reality they once represented. This representation of a ‘comely’ milkmaid, reminiscent of earlier hawkers, reappears on a menu card for a dinner on board the SS Carthage by the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. But their image has moved far beyond that now. According to recent fashion trends, it appears that the properties of the milkmaid and her associations with health have long outlasted their career. “Milkmaid chic” emerged out of post-Covid optimism to suggest that the wholesome image of the milkmaid look was aspirational and glamorous. A resurgence in the need for invigorating country air, exercise and entertainment has apparently revived the image once again.

About the author

Julia Nurse

Julia Nurse is a collections research specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in Art History and Museum Studies. She currently runs the Exploring Research programme, and has a particular interest in the medieval and early modern periods, especially the interaction of medicine, science and art within print culture.