In September 2021, the UK Home Secretary ordered a review into possession of nitrous oxide gas, one of the most popular recreational substances among 16- to 24-year-olds. Inhaling the gas may be a rising trend, but as historian Sharon Ruston reveals, it’s by no means a new activity. Laughing gas, as it was commonly known, could be found in some of the most respectable and fashionable homes of 19th-century Britain.

Laughing gas and the scientific pursuit of the sublime

Words by Professor Sharon Ruston

- In pictures

It all started with the chemist Humphry Davy’s refusal to accept the accepted opinion that nitrous oxide was fatal if inhaled. He was convinced that pneumatic medicine – treating diseases with airs or gases – was the key to human health and happiness. Davy did this work at the Medical Pneumatic Institute in Bristol, which he was appointed to superintend two months before his 20th birthday in 1798.

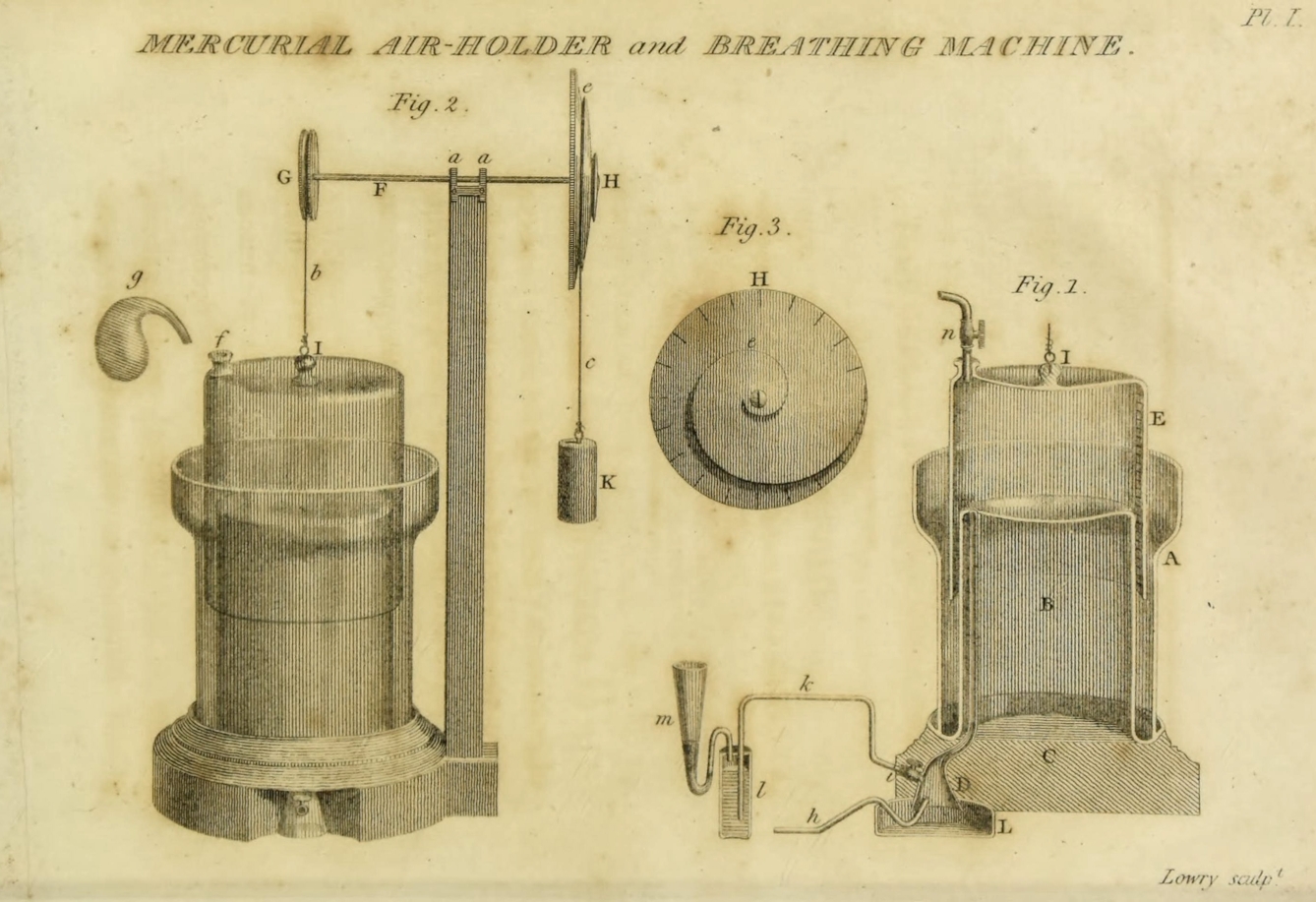

Thomas Beddoes established the Medical Pneumatic Institute in Clifton, Bristol particularly to trial the efficacy of gas treatment on diseases like consumption (tuberculosis). Beddoes was helped financially by the Wedgwood and Watt families, whose relations had been affected by consumption. The apparatus for the Institute was designed by James Watt. Sympathising with the revolutionary fervour that had gripped France at this time, Beddoes was known to some as the “little fat Democrat”. He had been made to resign his professorship in Chemistry at the University of Oxford in 1792 because of these associations.

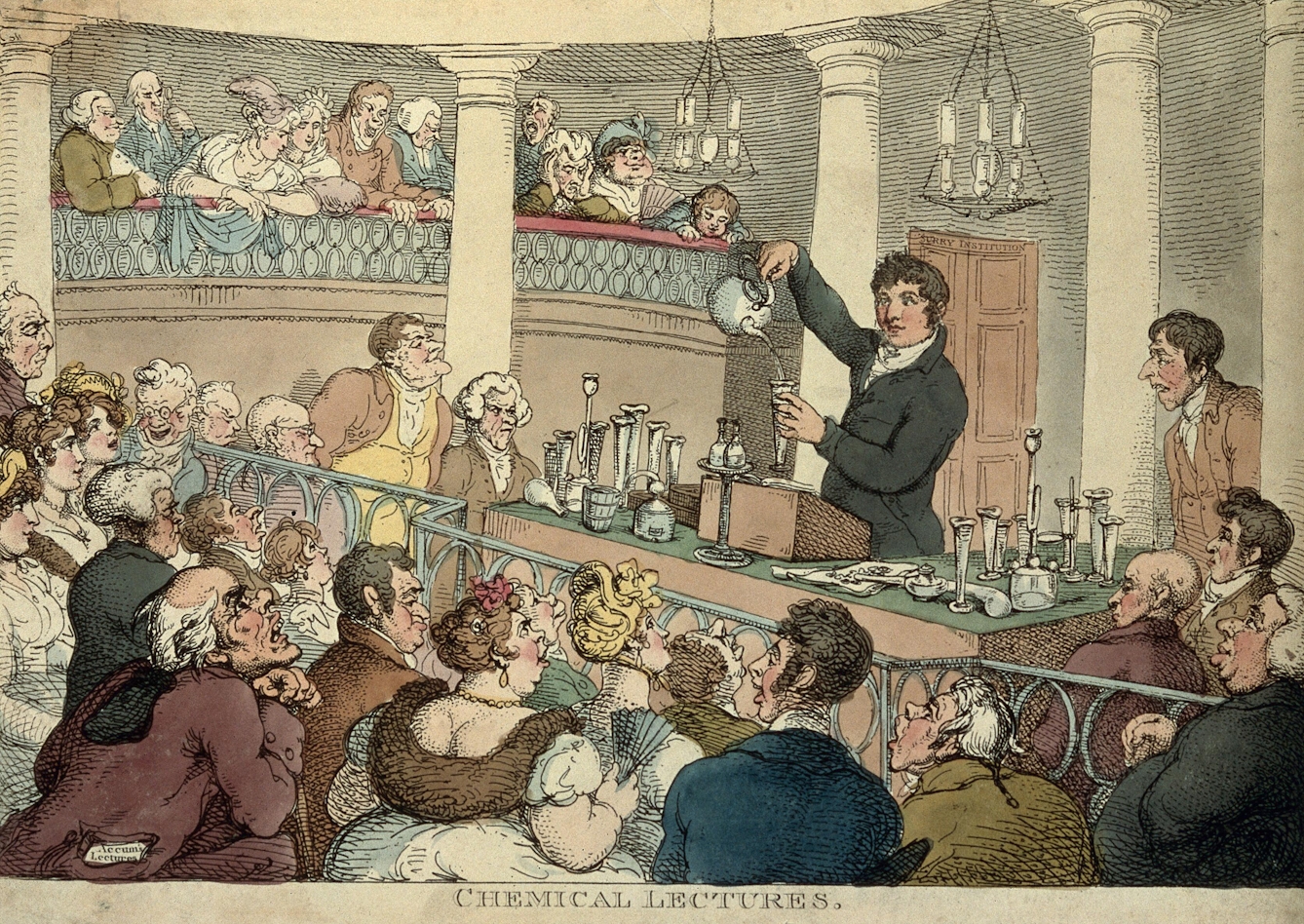

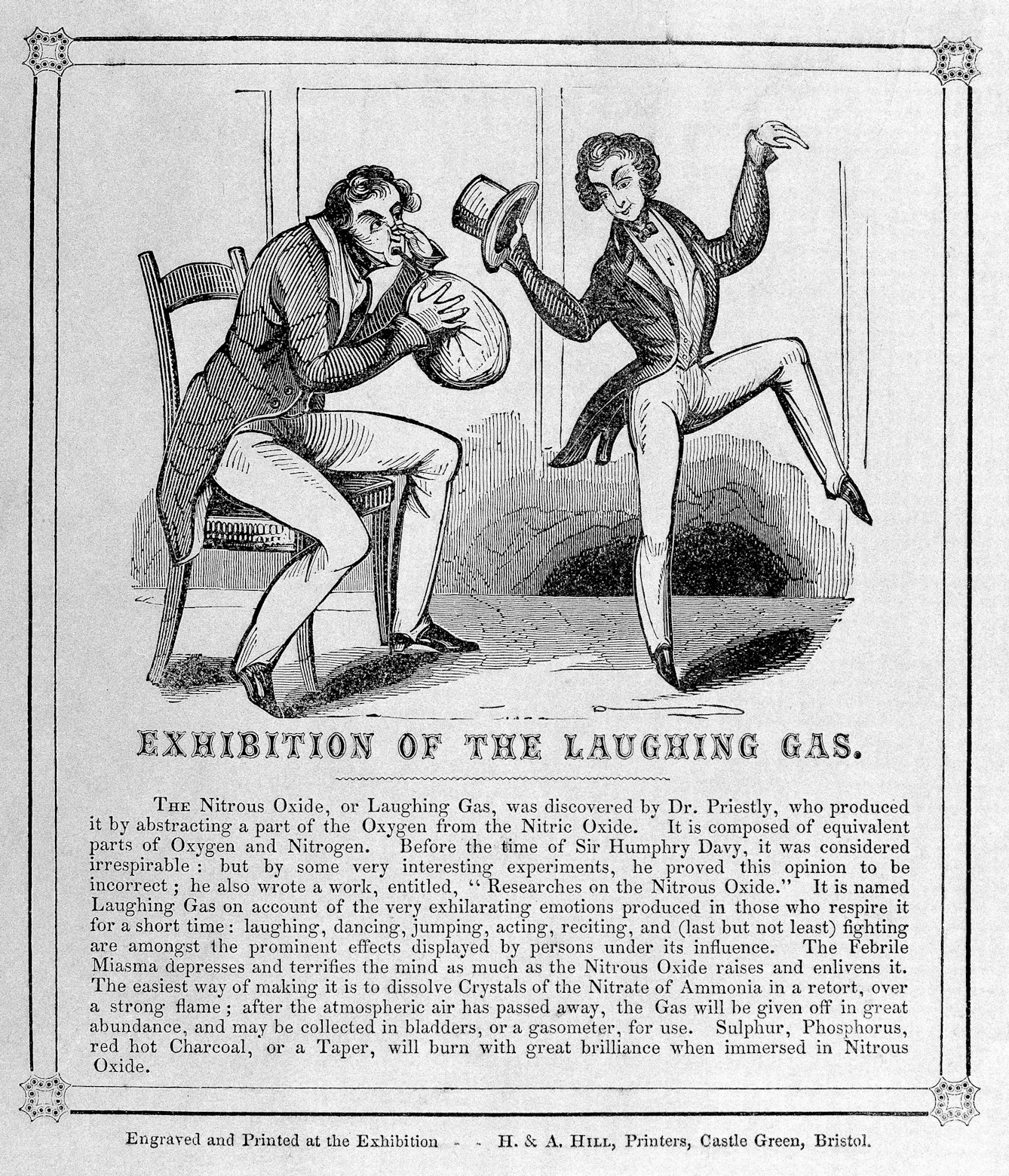

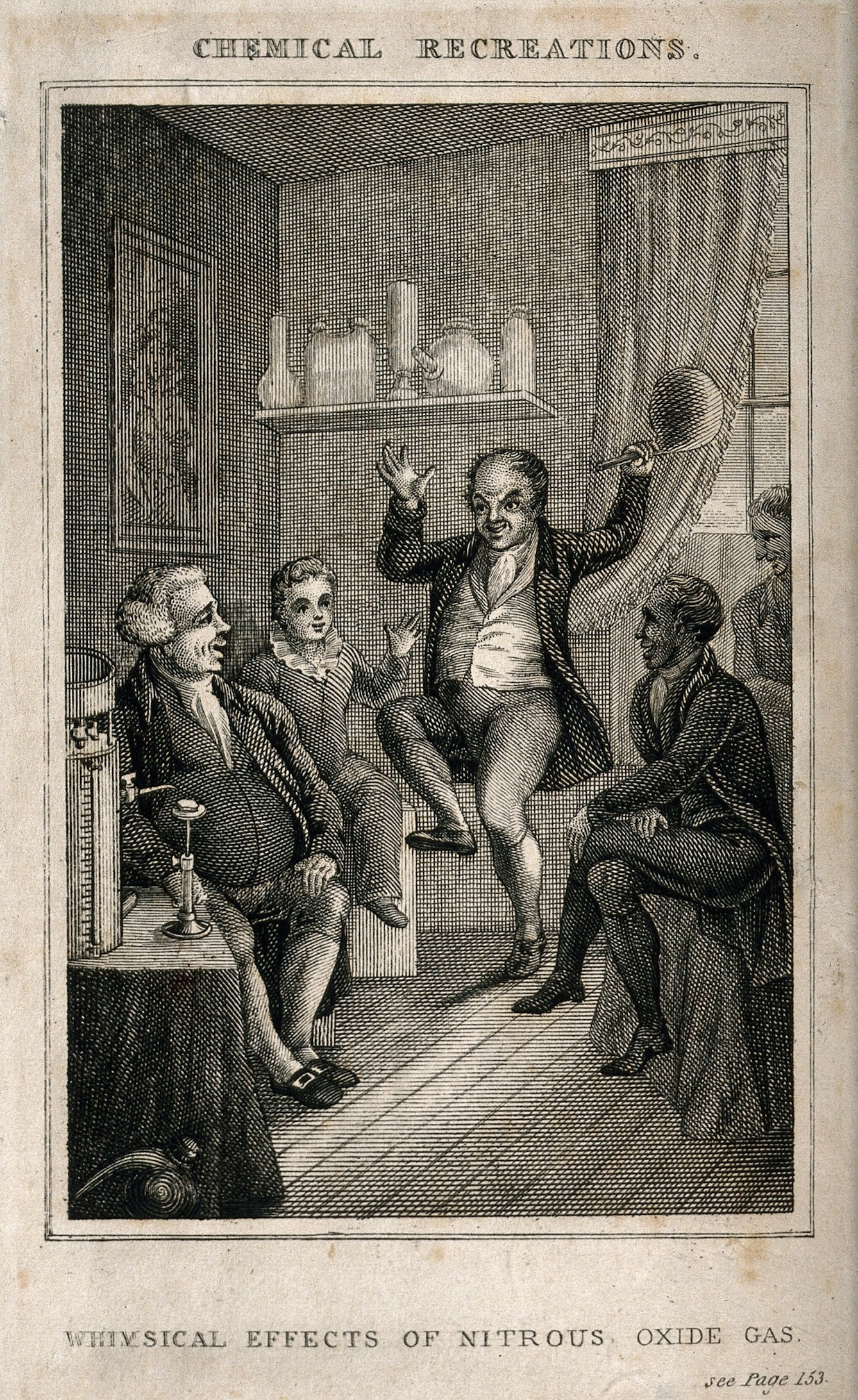

An American chemist, Samuel Latham Mitchell, had warned against breathing nitrous oxide, but on 18 April 1799, Davy wrote to a friend stating how important it was to repeat such experiments oneself. He described the effects of his self-experimentation as euphoric: “I have found a mode of obtaining it pure, and I breathed to-day, in the presence of Dr Beddoes and some others, sixteen quarts of it for near seven minutes. It appears to support life longer than even oxygen gas, and absolutely intoxicated me... this gas raised my pulse upwards of twenty strokes, made me dance about the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since.” As this mid-19th-century informational print suggests, scientific investigation was not without its pleasures.

Beddoes publicly announced the discovery of an entirely “new pleasure” in nitrous oxide gas at the Pneumatic Institute. Beddoes, who had married Anna, the sister of novelist Maria Edgeworth in 1794, welcomed many literary friends and associates to the Institute in Bristol, including the poets Anna Barbauld, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey (who would become poet laureate) and Peter Mark Roget (who would go on to write ‘Roget’s Thesaurus’). They came to the institute to talk politics, chemistry and poetry, and were keen to try the new gas.

Davy’s experiments with nitrous oxide continued and he recorded in his notebooks how much he and his colleagues took, at what times, and what were the effects. He records one instance where, in order to “determine [whether nitrous oxide] was stimulant or depressing”, he drank a bottle of wine in eight minutes to compare the effects. But when he then breathed some pure nitrous oxide, he forgot about the headache caused by the wine and experienced “the usual pleasurable thrilling”. Almost as an aside, Davy mentioned in his book, ‘Researches Chemical and Philosophical’, that “as nitrous oxide in its extensive operation appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations”. It would take many more decades before this anaesthetic property was recognised by others.

Before long, nitrous oxide was associated with creative types, such as poets and musicians. Southey wrote in a letter to his brother: “Davy has actually invented a new pleasure for which language has no name.” Henry Wansey described “sensations so delightful, that I can compare them to no others, except those which I felt (being a lover of music) about five years since in Westminster Abbey, in some of the grand choruses in the Messiah, from the united powers of 700 instruments of music”.

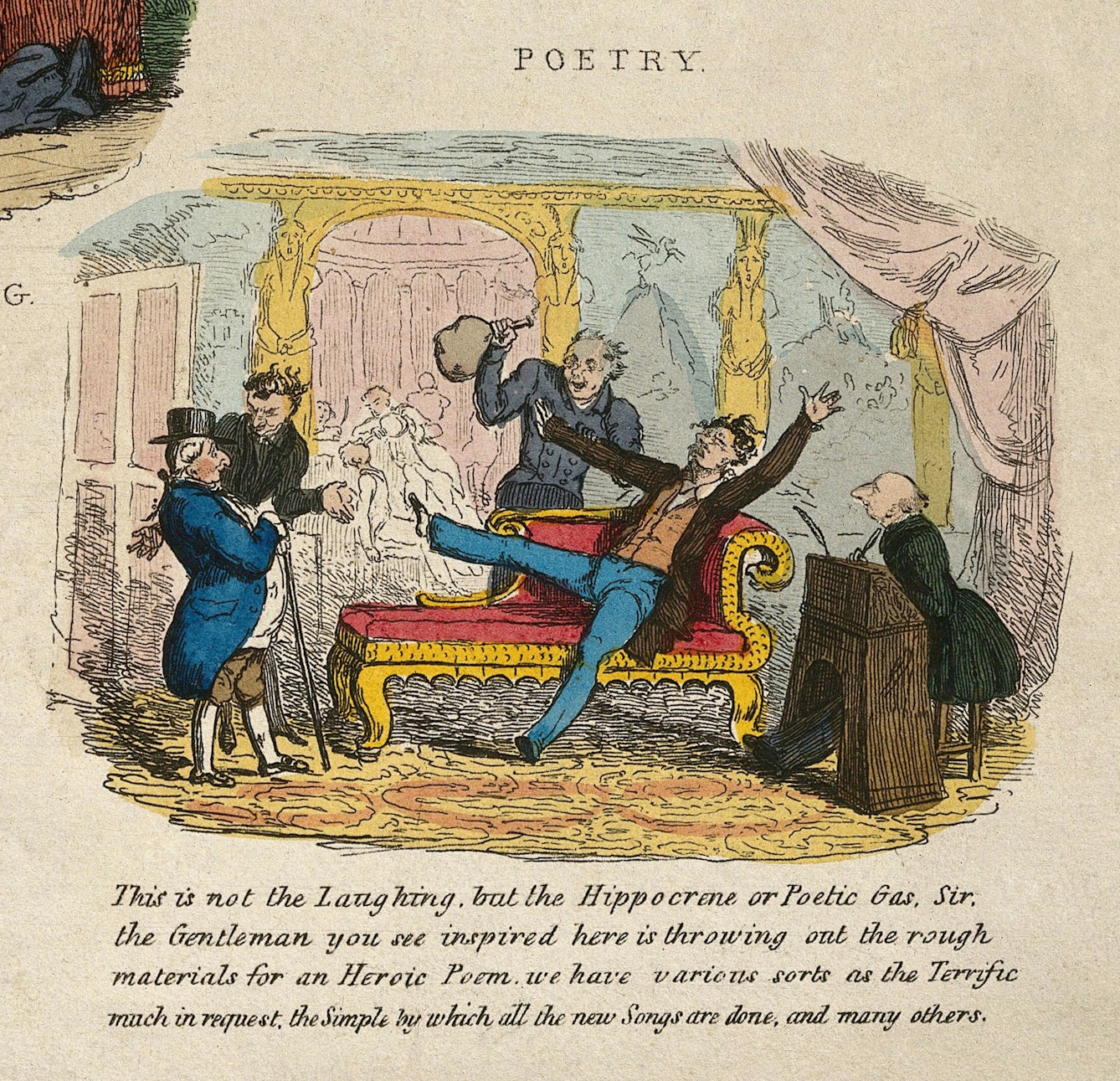

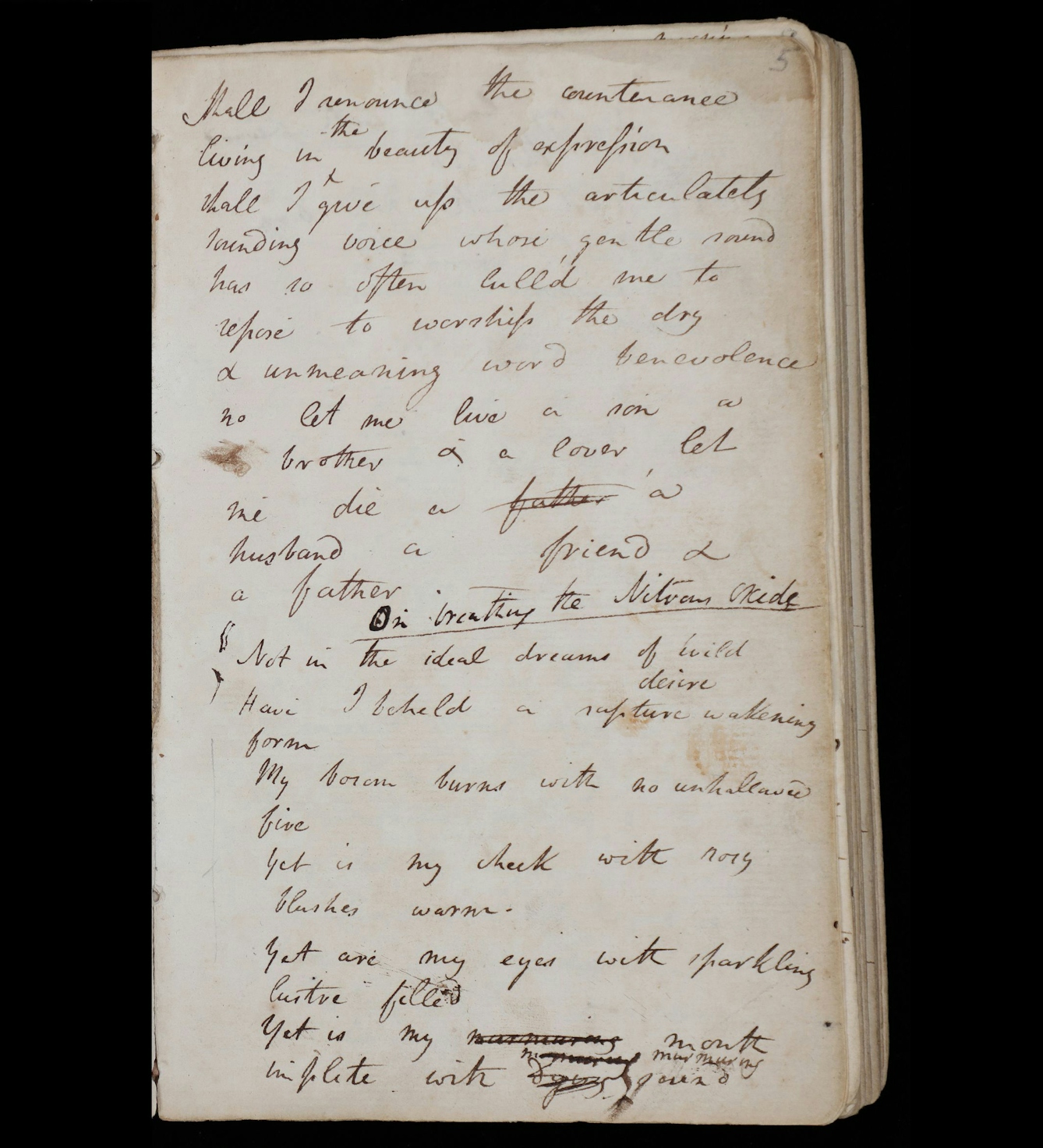

Davy focused on the creative potential of nitrous oxide in his account of its effects. He would take a green silk bag of gas on moonlight walks in order to artificially create the sublime feelings associated with poetry or music. In his book he recounts how “on May 5th, at night, after walking for an hour amidst the scenery of the Avon, at this period rendered exquisitely beautiful by bright moonshine; my mind being in a state of agreeable feeling, I respired six quarts of newly prepared nitrous oxide”. Later that night, he fell into an “intermediate state between sleeping and waking” of “vivid and agreeable dreams”. He even wrote his own poem titled ‘On Breathing the Nitrous Oxide’, perhaps when under the influence of the gas.

Not everyone treated the new gas with such reverence. It became an easy target for parody and the subject of several popular caricatures. Public science demonstrations were ridiculed by James Gillray in a cartoon called ‘Scientific Researches! New Discoveries in Pneumatics! Or an Experimental Lecture on the Powers of Air’, which shows Davy participating in a lecture at the Royal Institution in London in 1801. While Davy wields bellows in the background, a member of the well-to-do audience is administered the gas, and it is emitted rather unceremoniously from his backside. These portrayals may have encouraged Davy to transfer his attention to his new and exciting studies in electrochemistry.

This print in the style of caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson's illustrations for the satirical poem ‘The Tour of Dr Syntax’ (1812) shows a wealthy drawing room where patients cavort with wild abandon under the influence of the gas. The doctor, in his traditional black apparel, seems also to have inhaled the gas, and joins in the festivities. A servant looks on, perhaps laughing at his employers. One of the dancing women accosts another startled servant in livery in a manner indecorous to her gender and social standing. The whole serves to mock the lifestyles of the rich.

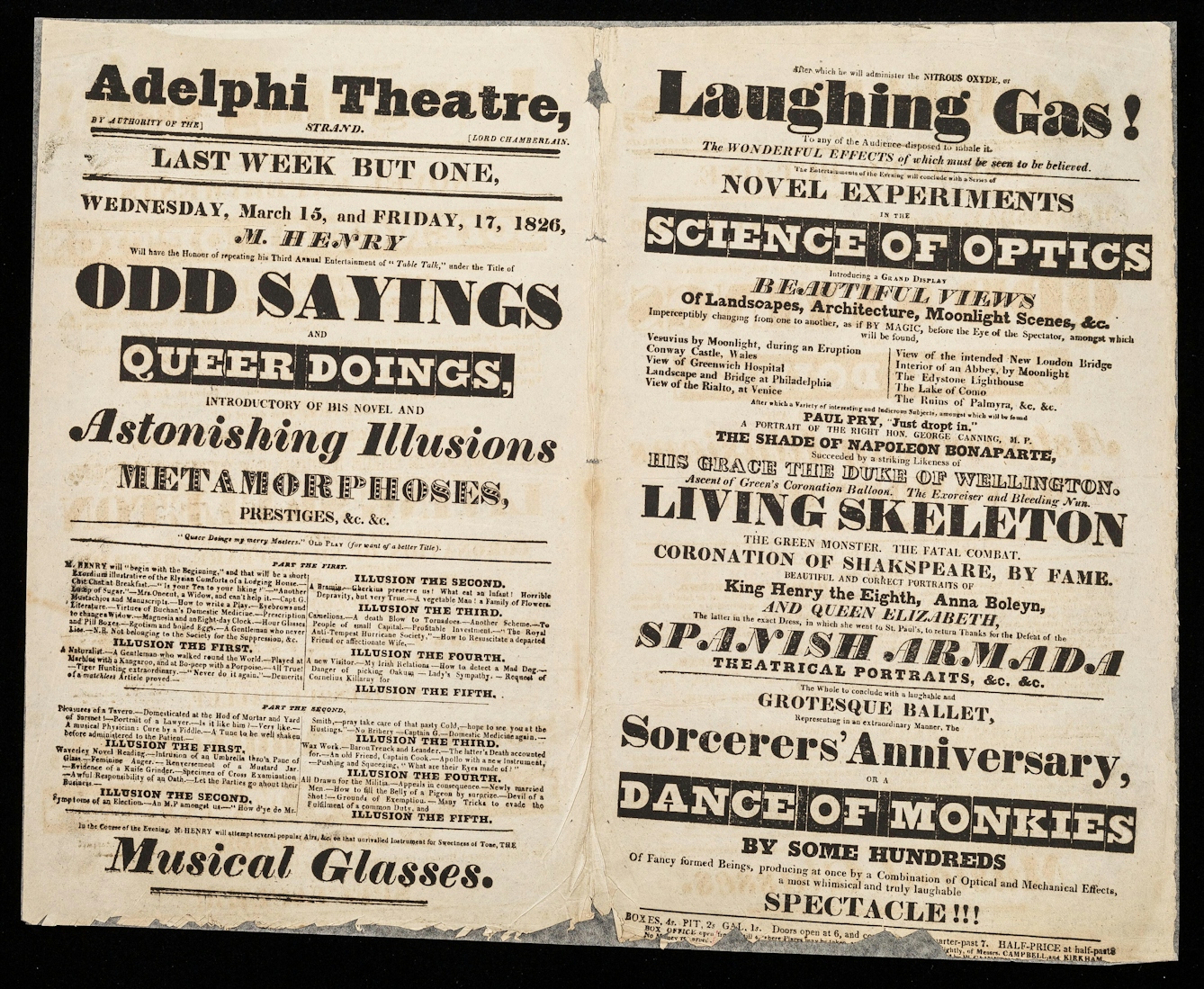

By 1826, when this playbill is dated, inhaling nitrous oxide has become a theatrical entertainment. In the Adelphi Theatre an entertainer called M Henry promises to administer the gas “to any of the audience disposed to inhale it” in order to witness the “wonderful effects” that “must be seen to be believed”. The recipient of the gas, not in control of his body’s response, ‘performs’ for the amusement of the audience. Just as animal magnetists and, later, hypnotists would take their demonstrations from the laboratory to the stage, nitrous oxide has become less a medical treatment than a theatrical spectacle.

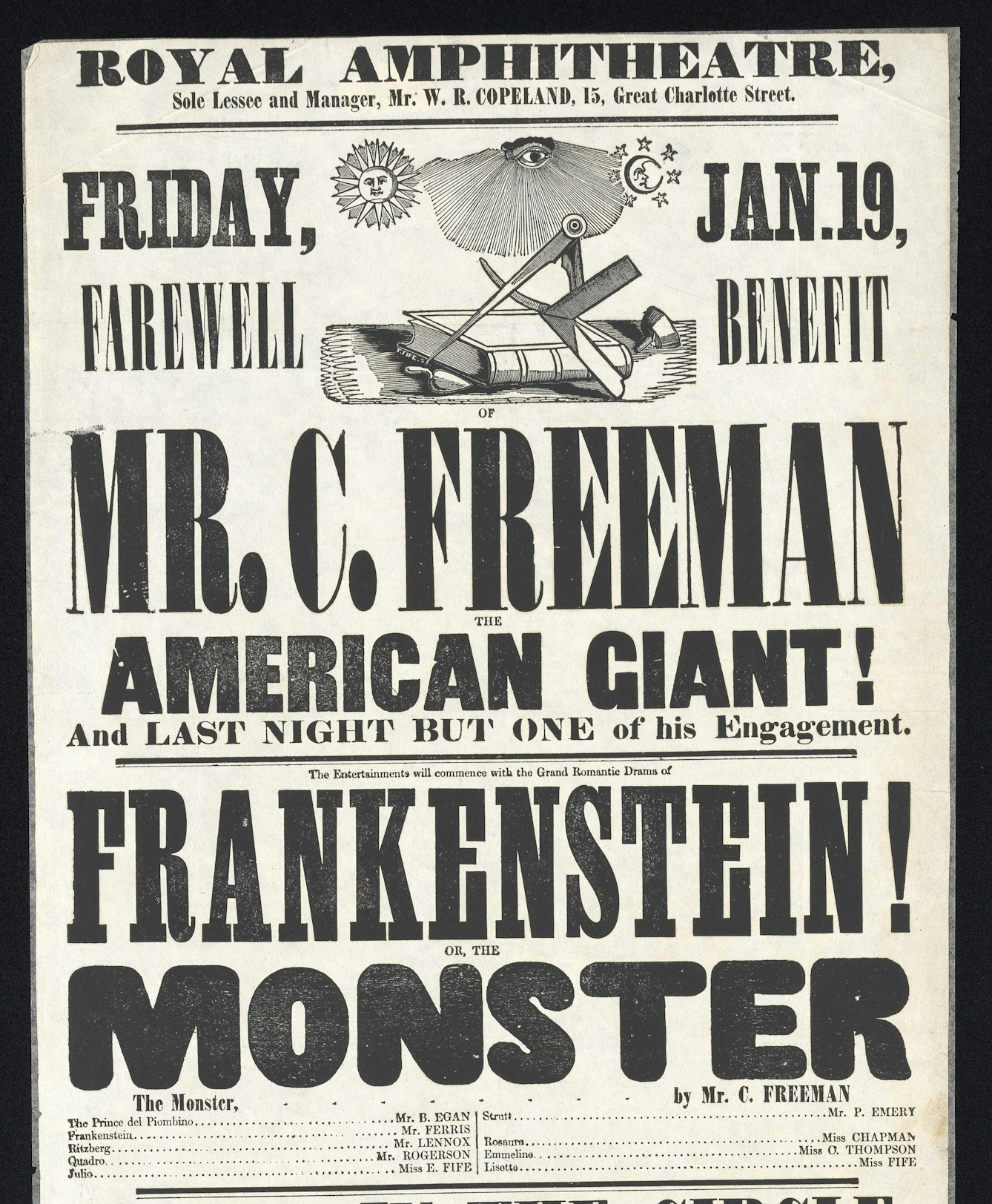

As this flyer shows, Mary Shelley’s novel ‘Frankenstein’ (1818) was also adapted as a spectacle for the popular stage. Shelley was reading Davy’s ‘Chemistry’ while writing her book and there are a number of similarities between Davy and Victor Frankenstein. While studying chemistry at university, Frankenstein notes that understanding “the nature of the air we breathe” is one of the main achievements of “modern chemistry”. It is Victor’s desire to match and even exceed the achievements of his peers in chemistry that leads him to create a living being from dead bodies. We can see this same drive in Davy’s pursuit of his nitrous oxide experiments, alongside the need to ensure more rigorous parameters for scientific experimentation.

About the author

Professor Sharon Ruston

Professor Ruston is Chair in Romanticism at Lancaster University. She has written the following books: ‘The Science of Life and Death in Frankenstein’ (2021), ‘Creating Romanticism’ (2013), ‘Romanticism: An Introduction’ (2010), and ‘Shelley and Vitality’ (2005). She also co-edited the ‘Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy’ for Oxford University Press (2020). She currently leads an AHRC-funded project to transcribe all of the notebooks of Sir Humphry Davy.