At 70, Chris decided to begin counselling to understand himself and what he’d been through better. Accessing his hospital records was a significant and clarifying experience, and as he opened up to his counsellor, he began to think about sharing his life story to benefit other intersex people.

Journeying home

Words and artworks by Chris Northaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

At an age when most people may feel they know where their lives have been and are going (maybe even knowing too much, resulting in midlife crises!), I still had many unanswered questions.

In 2016, I experienced blood clots on both lungs, which pulled me up with a jolt and brought my mortality into focus. This new health warning was a catalyst to begin counselling and start looking into the secrecy about my childhood medical history that had been imposed by doctors.

Counselling enabled me to open up, helped me better understand myself and the traumatic experiences I’d been through early in my life, but the longstanding secrecy remained and body shame remained.

The legacy of secrecy

The meetings with my counsellor enabled me to look back on the lack of understanding and care given at other times in my life, and I realised how unsupported I and my family had been over the years.

Throughout life, because of imposed secrecy, I’d felt gagged, unable to tell anyone about being intersex. I felt shame and feared people might misunderstand and misjudge me.

Evidence from Amnesty International confirms that many intersex people they spoke to reported lasting negative impacts on their health, sexual lives, psychological wellbeing, and gender identity. Doctors should never tell parents to keep their child’s medical history a secret.

Once, in my mid-40s, I tried talking to Mum about my life, but Dad heatedly said, “Don’t upset your mother!” and it was never mentioned again.

I now deeply regret I’d felt unable to talk with my immediate family about being intersex. I never told them they weren’t to blame for what I’d been through. I felt guilty about how my life may have adversely affected them, but sadly the counselling, which gave me some understanding and confidence, came too late.

From the day I was born, none of my family ever received the support they should have been offered. When I most needed appropriate explanations about my body, life and feelings, that didn’t happen.

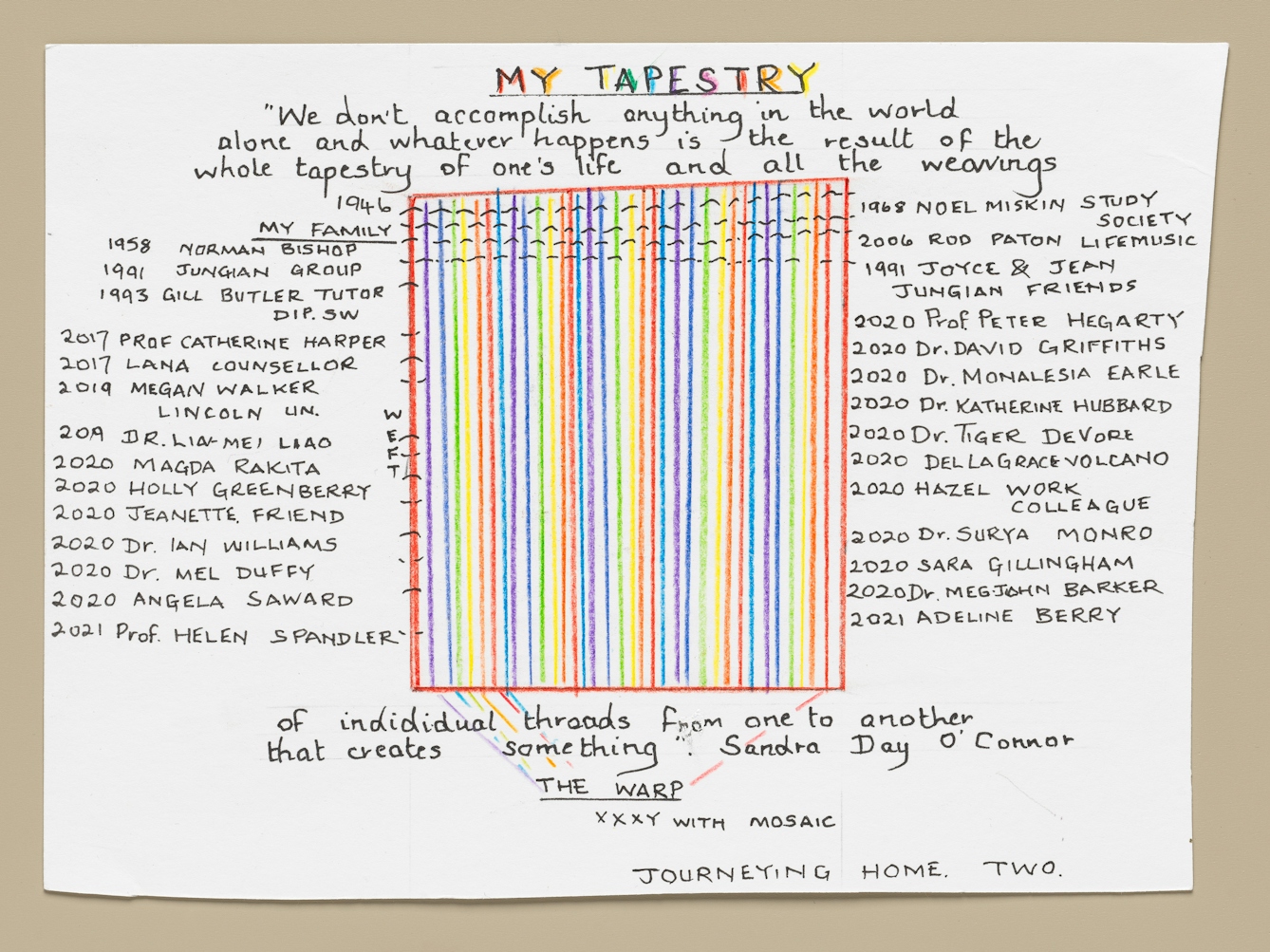

‘My tapestry’ by Chris North, 2023.

Revelations in my hospital records

In 2018, gaining access to my Great Ormond Street Hospital records was a breakthrough, as I began to read details of what had happened to me from the earliest age. Events that I had traumatic memories of – being tied to my bed and later photographed naked – were recorded here. My medicalisation and them not seeing me as a “whole person” was also clear.

I read how, behind the scenes, the child psychiatrist was working on my behalf, but I can’t recall that; I don’t think it was made clear to me at the time, or I’d blotted it out.

When I’d undergone a non-consensual total hysterectomy aged 13, it not only removed my female reproductive organs but any opportunity I could have had to choose to be a girl.

My hospital records from the time said, “…the child should have been brought up as a girl but as he’d been brought up as a boy… the psychological trauma of a changeover would be insurmountable”.

Breakthroughs in intersex healthcare

Most intersex people interviewed by Amnesty International stated that surgeries they’d undergone as children were non-emergencies performed to make them conform to the standard norm of what a girl or boy ‘should’ look like.

Unless a child’s health is at risk, surgery on intersex babies should be delayed until they can make their own informed choice, but these surgeries continue today.

However, due to pressure from activists, in 2020 hospitals began to pledge to end intersex surgeries and in 2021 New York City Health & Hospitals instituted a rule to defer all medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children. Kimberly Zieselman, an attorney, human-rights advocate, author and intersex woman, played a significant role in winning a series of landmark victories regarding these surgeries.

This is a breakthrough for the children who will not have surgery performed on them until they are able to give their own informed consent, but is tinged with sadness for me, as the beginnings of these wider changes come too late in my life.

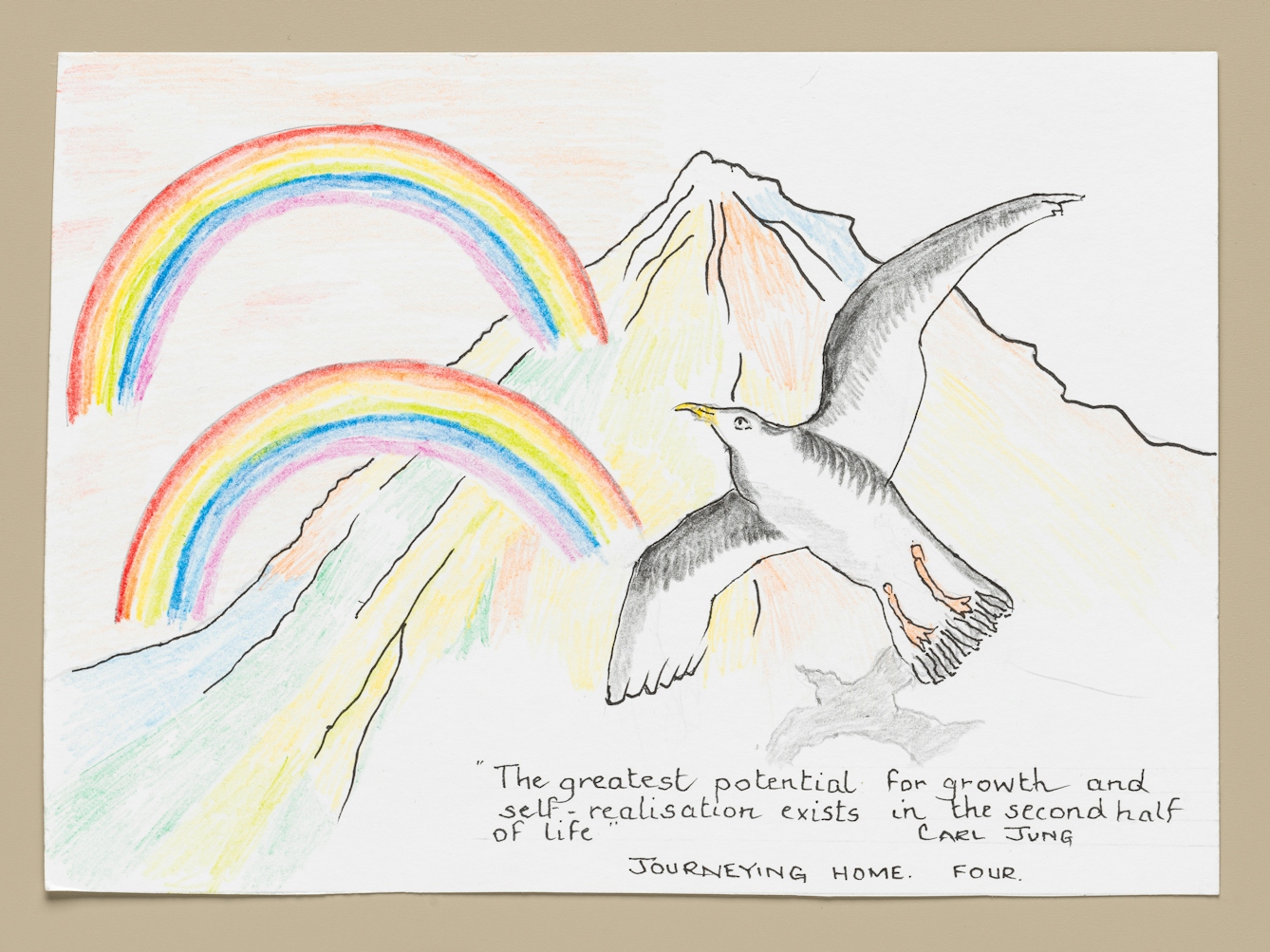

‘Journeying home’ by Chris North, 2023.

Sharing my story

By 2019, I’d received two years of counselling, which gave me a better understanding of myself and encouraged me to open up, and my counsellor said “the time was right” to complete my autobiography.

That year, I’d planned to attend an intersex conference, but had hit a nerve through self-injection and couldn’t walk, so I contacted some people connected with the event. Through them, and especially Professor Peter Hegarty, in 2021 I gave my online testimony at Dublin University’s ‘Intersex 2021’, an international conference.

I then wrote an article about my life’s journey for the mental health magazine Asylum, and co-wrote a chapter with Professor Peter Hegarty in the 2022 book ‘Interdisciplinary and Global Perspectives on Intersex’.

Stepping out into these safe spaces gave me confidence to stop writing under a pen name and begin using my own name, and helped me continue to tell my story to some colleagues, friends and family.

Though I encountered misconceptions, the negative responses I’d half expected didn’t happen. I experienced an enormous sense of relief, now felt part of a wider intersex community, and had a sense of belonging; this supportive ‘tapestry’ was fundamental in encouraging me to work as a campaigner and activist.

Even today there is a lack of awareness or understanding about what it means to be intersex. I told a friend that I was intersex, and she replied she’d seen a documentary about a male ballet dancer who was transgender. This is a common misunderstanding.

Intersex relates to biological sex (a physical difference), which may involve the genitals, internal sex organs, chromosomes, hormones or a combination of some or all of these – it is distinct from a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. An intersex person may identify as straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual or transgender, and may identify as female, male, both or neither.

Hope for intersex lives today

Within the recent and growing intersex community, there is increasing determination and drive for change that did not exist in 1946, when I was born.

Organisations now exist to support intersex people, for example. OII Europe (Organisation Intersex International Europe) is the umbrella organisation of European human rights-based and intersex-led organisations, whose vision is “of a world where the human rights of intersex people are fully implemented”. In the UK, Interconnected UK and Intersex UK provide, among other things, peer support and a safe space.

Progressive intersex-themed books have recently been and are being published. They go beyond physical health to promote the need for psychosocial and creative healthcare. Examples include Dr Lih-Mei Liao’s ‘Variations In Sex Development’ (2023), and Fae Garland and Mitchell Travis’s ‘Intersex Embodiment’ (2023). The intersex youth anthology ‘YOUth&I’ shares the stories and experiences of intersex young people. Three editions have been published so far, and the editors welcome contributions from around the world.

As I mentioned above, Dublin University hosted an intersex conference in 2021; in addition, ‘Centring Intersex’ took place at Huddersfield University in 2023. These conferences provide networks for psychosocial research, pressure to introduce laws to protect intersex people, and a platform for relevant agencies and stakeholders to generate change.

Chris North at a family barbecue, 2023.

Significant research, conferences, books and organisations are promising signs, but there remains an implementation gap between them and their impact on intersex lives.

Sharing our own lived experience has the power to help people to see why the research and campaigning really matters. We bear witness to what’s needed in the understanding of and care for intersex people, without which serious consequences remain in our intersex lives.

I want to play my part in raising awareness as an older intersex person; be trusted to make my own choices; be listened to, supported, and loved for who I am, and not what society expects of me.

This is my hope and dream for all of us who are intersex, whatever our age.

Be Proud of Who You Are

Nobody knows the pathway you’ve travelled

The things you’ve been through or seen.

The remarkable strength you’ve shown in your life

Making sense of experiences, what they mean.Nobody knows how it feels to be you

Sometimes confused and unsure.

Other times achieving, gaining success,

A banner with “WELL DONE !” on your door.You are unique, an individual “one-off”,

You’ve a right to be proud of who you are.

You are capable of amazing things

You are brave, you are strong, you’ll go far.Go in front of the mirror, look at yourself,

The tough hard things you’ve been through.

Looking back from the mirror is a special someone

And that really special someone is YOU!

About the author

Chris North

Chris North is an author, independent scholar, creative arts facilitator, intersex advocate and activist. He’s been a teacher, social and community worker and is now a storyteller. He shares his powerful personal experience to provide much-needed “lived historical intersex testimony” and works hard for other minorities and those marginalised by society.