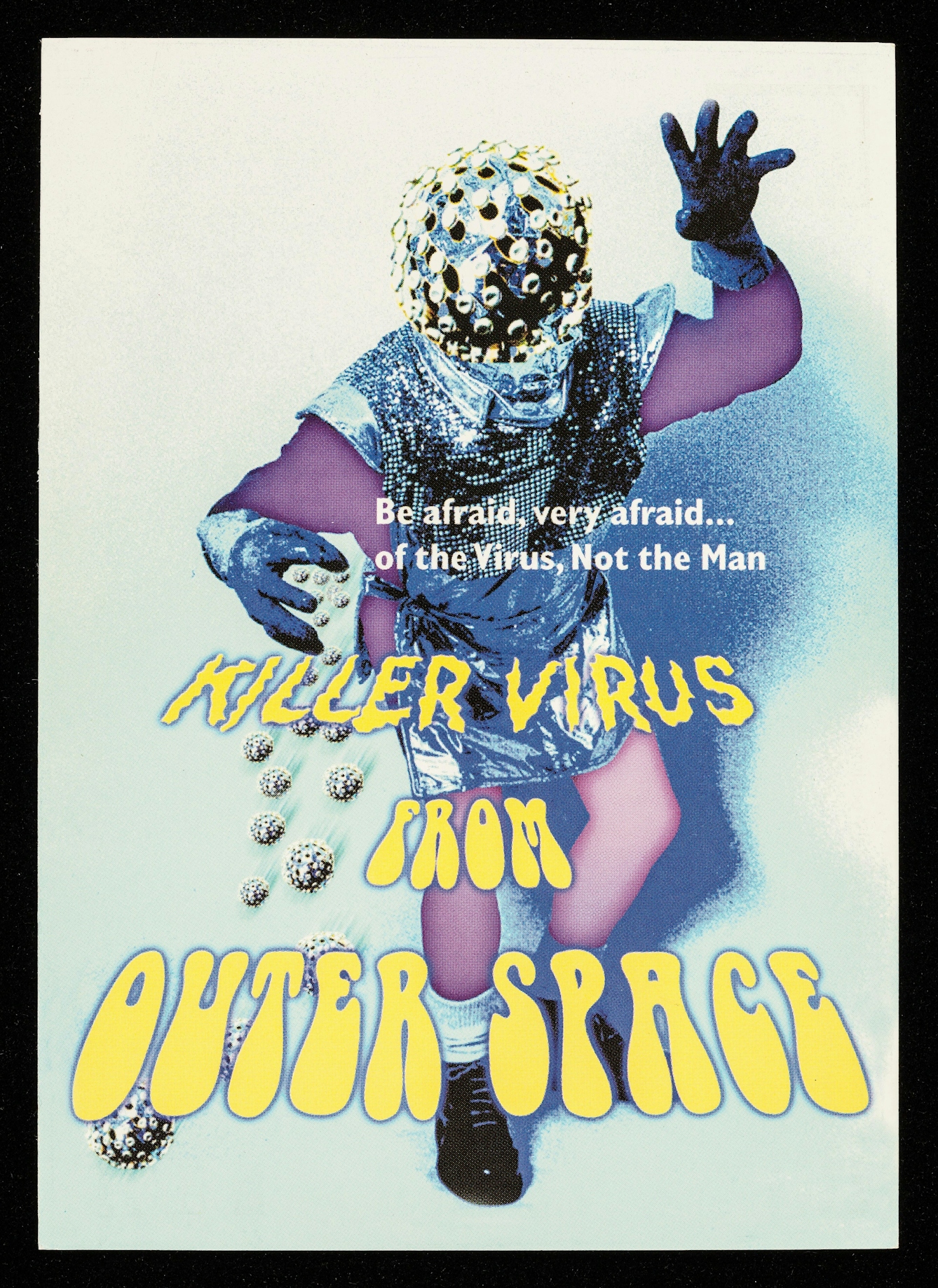

During the first lockdown, the death of a close friend made David Jesudason want to know more about viruses and the people who discover them, so he read ‘The Viral Storm’ by Nathan Wolfe. The book had a big impact on David – in it, the author had warned why we were so vulnerable to a global pandemic, several years before Covid-19 swept across the world. Here David imagines himself as a virus – tiny but potentially deadly – and puts himself and those hunting him under the microscope.

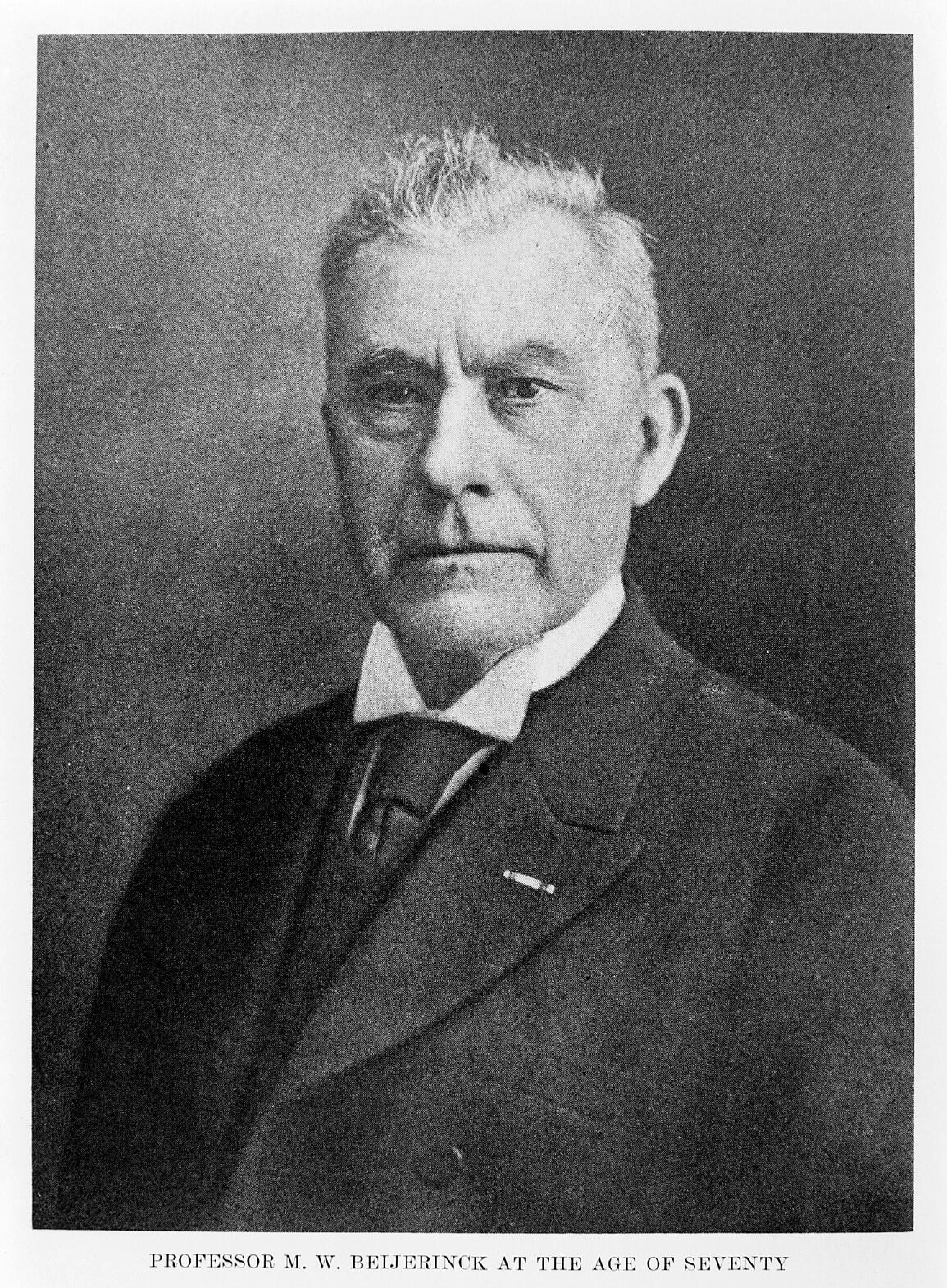

I’m a virus. I’m one of the smallest microbes. But what size exactly am I? Well, if a human were suddenly enlarged to the size of a football stadium, a bacterium would be the ball being kicked around. On that football there are 20 hexagonal patches – one of these would be the size of a virus. I was pretty much unknown until 100 years ago, when Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck concluded that a new form of life (me!) was causing mosaic tobacco disease in plants.

Beijerinck discovered me under a microscope in 1921, and he was the first person to use the term virus, which is Latin for poison. Beijerinck was just scratching the surface though: we viruses remain the “last frontier of undiscovered life on our planet”.

I’m very good at making animals ill, including monkeys. Humans’ closest relative first encountered viruses when hunting, and humans met us when farming and handling pets. One of the first people to die in Thailand in 2004 from “bird flu”, or highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), was a six-year-old boy who became seriously ill after handling a sick chicken. After the outbreak, antiviral medicine (my nemesis) was stockpiled, and vaccines were created and tested, but the threat passed.

The first real global pandemic was probably smallpox. It’s existed for 3,000 years and was everywhere by the middle of the 18th century, a spread accelerated by humans’ new-found love of travel. Smallpox was wiped out by vaccines, and big cities have taken other measures to help contain me and my cousins, including creating urban green spaces and public parks.

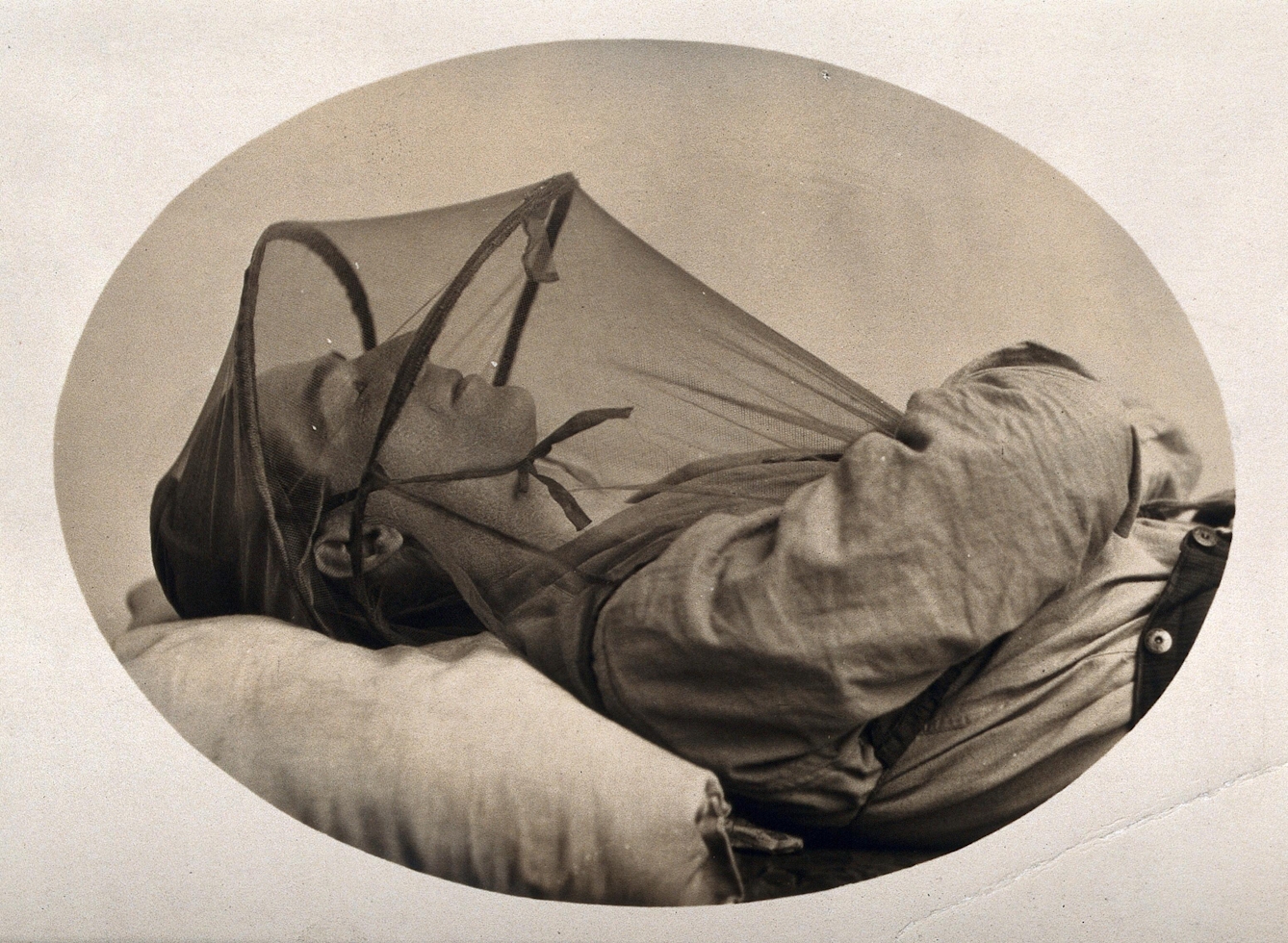

Viruses can evade death by living permanently and simultaneously in multiple hosts. For example, the dengue virus isn’t transferred from human to human but by mosquitos in tropical urban areas. It can lead to lethal complications, also known as “severe dengue”. Researchers used various brutal methods to discover more about dengue’s transmission, including placing primates in cages and lifting them into the forest canopy where mosquitos fed. The results showed that dengue wasn’t only a human disease.

Some viruses, such as monkeypox in tropical rainforest areas of Central and West Africa, have become endemic in humans and a permanent part of our shared world. But other viruses can be created without the help of animals. Lab-grown viruses are often intended for use as insecticides or vaccines but the dangers they pose are large. They have the potential to “radically transform both wildlife and human communities”.

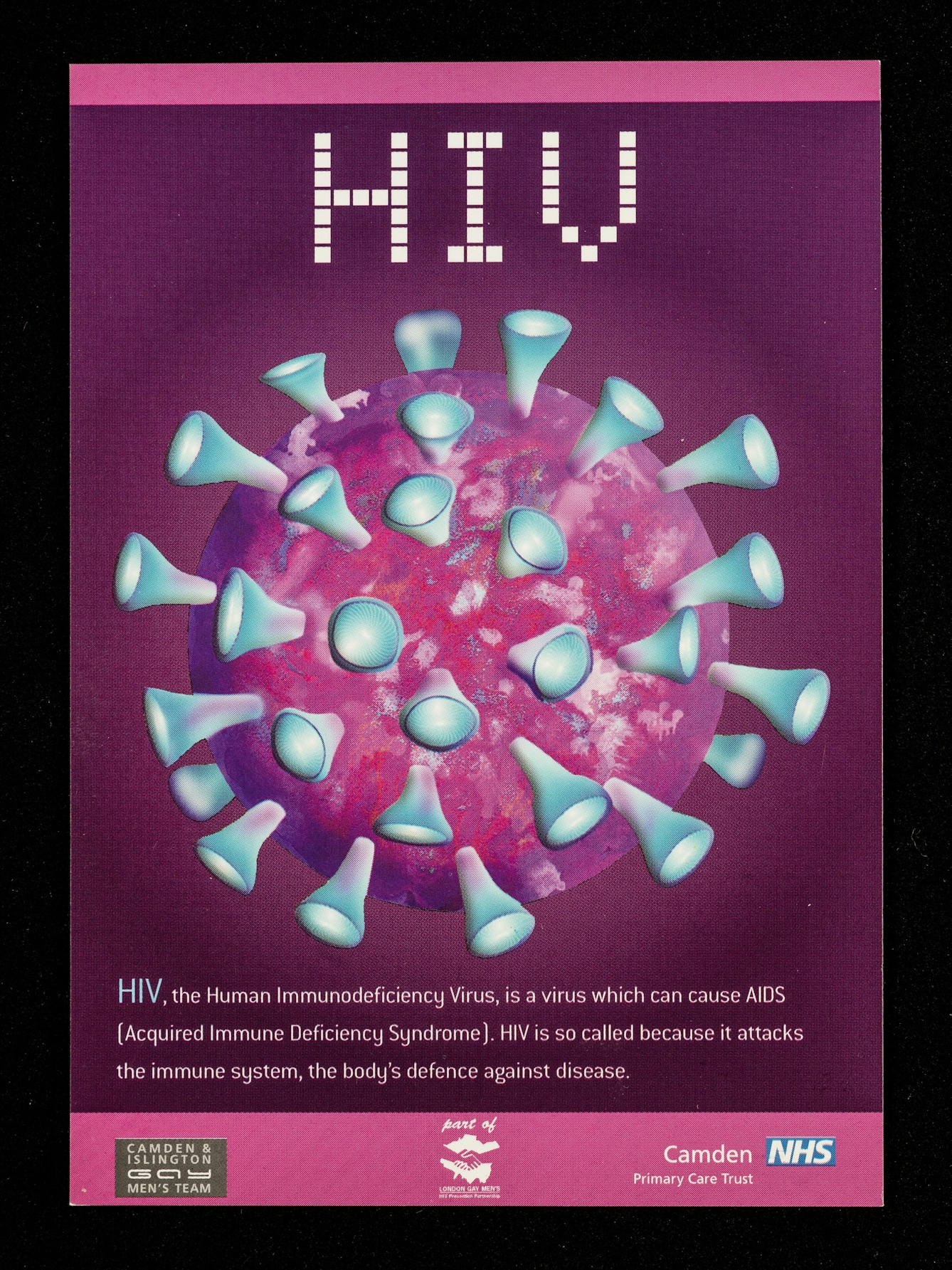

Scientists have been trying to contain pandemics for the last 100 years. In ‘The Viral Storm’, Nathan Wolfe argues that, instead of modifying behaviour and scrambling for vaccines and new drugs, humans should discover more of my cousins first. HIV, for example, was present in humans 50 years before it spread widely. Many lives could have been saved if it was stopped before it reached Central Africa. But can pandemics be predicted? Wolfe thinks they can, and has set up listening posts around the world aimed at catching new microbes.

Wolfe’s warnings about future global pandemics were largely ignored, and some have argued that his method of preventative discovery is impossible. But his belief that the world is currently ill-equipped to beat infectious diseases has been shown to be true. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is now ubiquitous and looks like it’s here to stay. Public health measures like mask wearing, hand hygiene (elbow bumps were first suggested by scientists in 2006 to beat avian flu), social distancing, lockdowns, air filtering, vaccines, quarantines and travel bans have all been used to stop the spread of Covid-19. Despite their use, viruses like me remain an everyday threat.

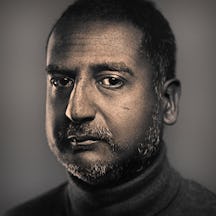

About the author

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.