First discovered 200 years ago, hydrogen peroxide has had multiple uses. It’s been used to investigate murders and propel rockets, as well as to treat teeth, clean contact lenses and bleach hair. David Jesudason celebrates a ubiquitous chemical compound that will always have a special significance for him because of its connection to 1990s club culture.

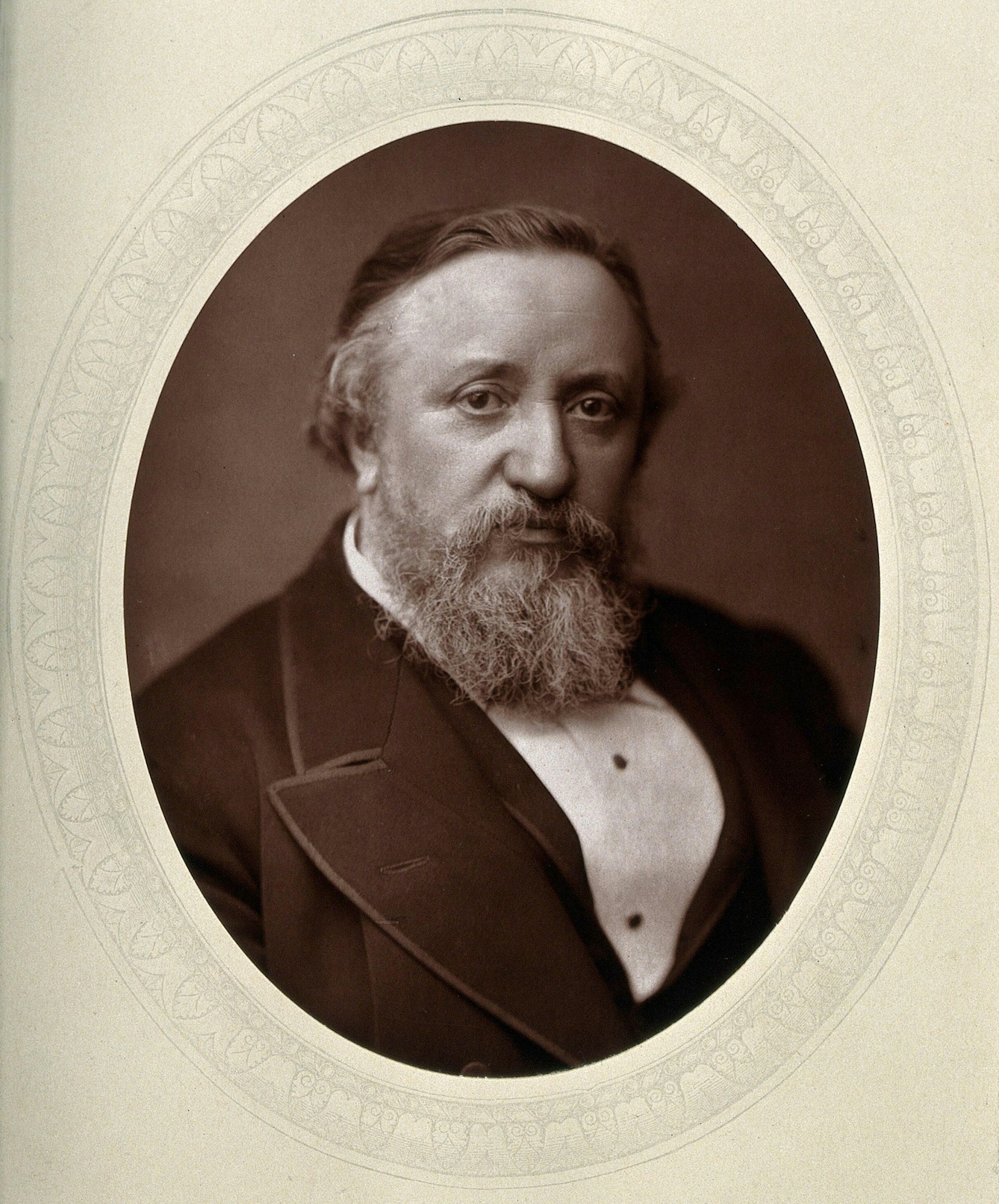

French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard may have been born a peasant, but his impact was considered significant enough for him to be named on the Eiffel Tower. Among other achievements, in 1818 Thénard discovered hydrogen peroxide while burning barium salts to make barium peroxide. When he placed barium peroxide in water, hydrogen peroxide was produced. He called it eau oxygénée. But even a visionary like Thénard would have struggled to predict hydrogen peroxide’s many uses, and how embedded it would become in popular culture.

Like Thénard, Sir Benjamin Ward Richardson achieved a huge amount during his lifetime. He lectured on forensic science, and was a passionate cyclist and prolific writer, penning biographies, plays, poems and songs. Richardson promised his mother on her deathbed that he would become a doctor, and he was one of the first to recommend that hydrogen peroxide should be used as an antiseptic. It may have fallen out of favour as a first-aid treatment, but it still has many eye-catching uses.

According to the ‘Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History’ by Victoria Sherrow, by the late 1800s hydrogen peroxide was being used to remove pigment from people’s hair. This left it yellow, or yellow-orange, but also very dry. In 1909, Eugène Schueller made a modern hair colourant containing hydrogen peroxide. He initially called his company the French Harmless Hair Dye Company, before renaming it L’Oréal. Only two per cent of people are naturally blonde, but Schueller’s invention saw this hair colour marketed as being the most desirable. Links to white supremacy were a leitmotif of Schueller’s life: he was a Nazi sympathiser who funded the far-right terrorist group La Cagoule.

The profits from peroxide-based hair dyes may have been used by L’Oréal’s founder to fund violence, but the chemical was also deployed by those on the right side of the law. In 1928, German chemist H O Albrecht discovered that hydrogen peroxide could be mixed with luminol and used to detect traces of blood. This enabled detectives to highlight evidence of murders in ways now commonplace in crime-procedural shows on TV, such as ‘CSI’ and ‘The Wire’.

Hydrogen peroxide is found in several ordinary household products, including solutions for cleaning contact lenses, and in whitening toothpaste and mouthwash. Hydrogen peroxide was first used in dentistry in 1913 for decreasing plaque formation and controlling gum disease. It’s still a common item in a dentist’s toolkit, used to treat the gum diseases gingivitis and periodontitis, as well as to whiten teeth. Beware personal teeth-bleaching products, though. In 2021, the consumer magazine Which? found that 58 per cent of teeth whiteners bought from online marketplaces contained illegal amounts of hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide has been used as both a tool of war and for treating war wounds. In 1934, three people were killed in Kummersdorf, the estate in Germany where the weapons office of the German Army was based, when a hydrogen-peroxide rocket exploded. Undeterred by this disaster, the Nazis used the chemical to fuel rocket attacks during World War II. It was one of the compounds that helped power V-2 missiles. Armies across the world continue to use propellant-grade hydrogen peroxide today.

But, for me, hydrogen peroxide will always be connected with peace and love. I liked electronic dance music when I was a teenager and would visit the ‘super-clubs’ of the 1990s and early 2000s, places like Turnmills in Clerkenwell or Bagley’s in King’s Cross. It was there that I first saw people waving glowsticks while dancing. The glowsticks would form gorgeous trails of colourful light, a luminesce caused by hydrogen peroxide triggering a chemical chain reaction. It was one of the few chemicals in rave culture to gave me so much innocent joy.

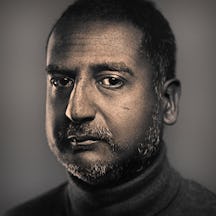

About the author

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.