Throughout history, the air we breathe has been linked to our health. Although medical understanding has shifted and grown, we still carry anxieties around the air we breathe and how it might harm us.

Miasma theory proposed that “bad air”, emitted by rubbish heaps or collections of human waste in towns, could travel, spreading disease and causing sickness. The air itself was to blame for poor health and disease transmission. Miasma theory was advanced by the Greek physician Hippocrates, but the belief had already been present in Europe and China for centuries.

The Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro encouraged the Roman government to drain swamps, which he believed caused stagnant ‘bad’ air to thrive, spreading disease. Varro anticipated the discovery of micro-organisms, believing there to be small invisible creatures in the air that were capable of spreading disease. Varro’s fear of their potential to spread disease is still relevant today in anxieties about the invisibility of harmful or toxic air.

As cities grew in the UK during the early modern period, so did the opportunity for disease to spread. The overcrowded populations, often living in unhygienic housing, created the ideal conditions for disease transmission. A widespread belief in the power of the air to transmit disease meant that people began to create ways to protect themselves. The 17th-century plague doctor’s mask had a snout filled with spices to purify the air the doctor breathed – helping to ‘clear’ the miasma from the air.

Similarly, the wealthy burned pleasant-smelling herbs in fumigators like the one pictured to protect themselves from this bad air. But not everyone was able to safeguard themselves according to the ideas of the time. This divide continued as the concept of bad air provided an explanation to the wealthy for the higher occurrence of disease in poor areas: rubbish-strewn areas with limited sanitation led to unpleasant smells in the air, thereby creating disease.

Cholera outbreaks in London during the 19th century reinforced miasma theory: how else could the disease seem to travel at random? Artwork from the time shows cholera travelling through the air, pouncing on certain individuals but leaving others free to live. After the 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho, scientist John Snow proposed the idea that something in the water, which he described as “cholera poison”, was to blame for the spread of the disease, rather than the air. This began a slow shift towards germ theory rather than miasma as the primary spread of disease.

Germ theory, as it was developed during the 19th century, proposed that micro-organisms, or pathogens, were responsible for causing disease. As these germs grew in the human ‘host’ body, this led to the spread and development of disease. As scientific beliefs shifted towards germ theory, miasma became an outdated concept for understanding disease outbreak and was often ridiculed as pseudo-science. But air was still important to health: in the 20th century, anxieties around air were related to its quality and health-giving properties, rather than the anxieties about disease that characterised the thinking of earlier centuries.

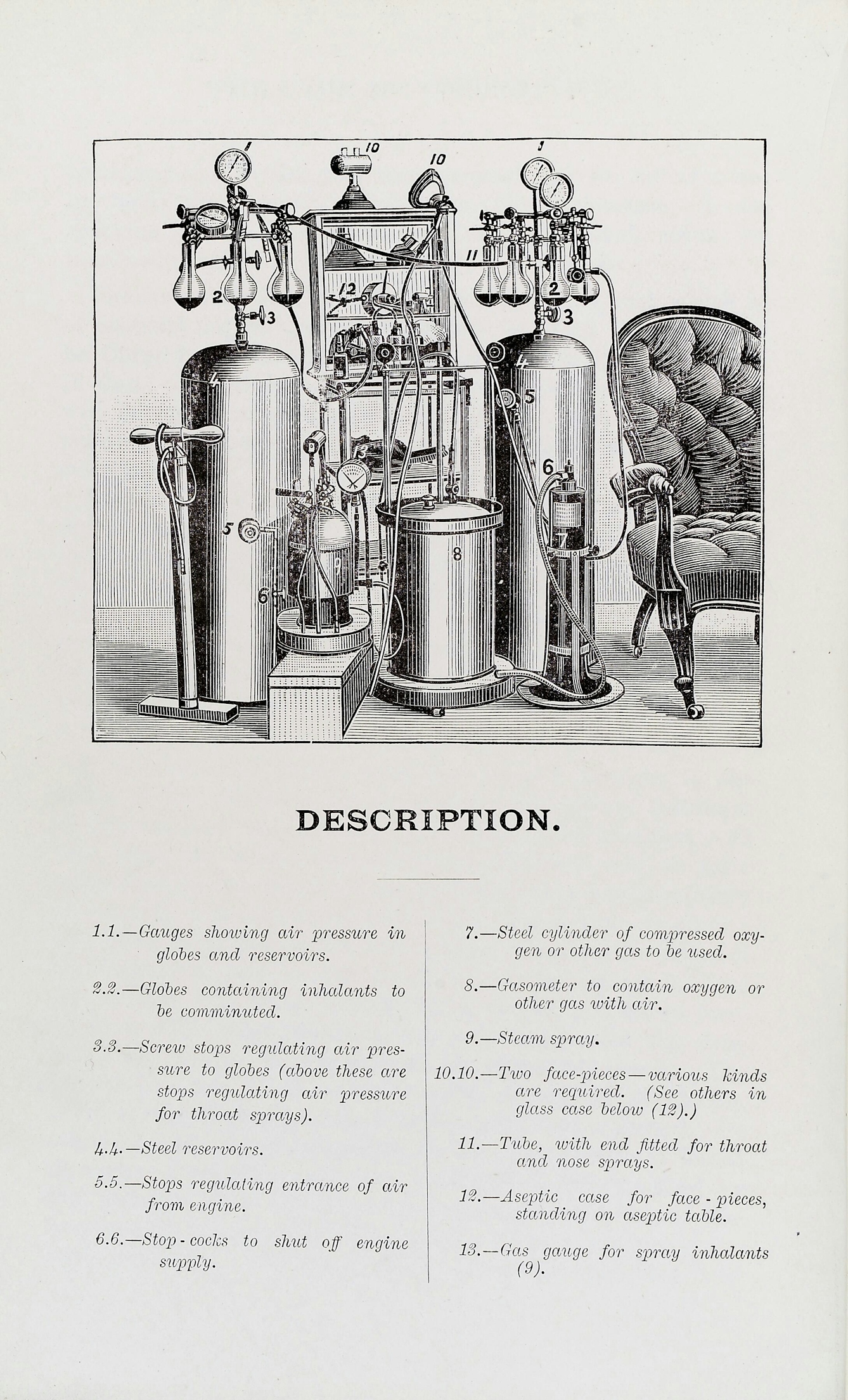

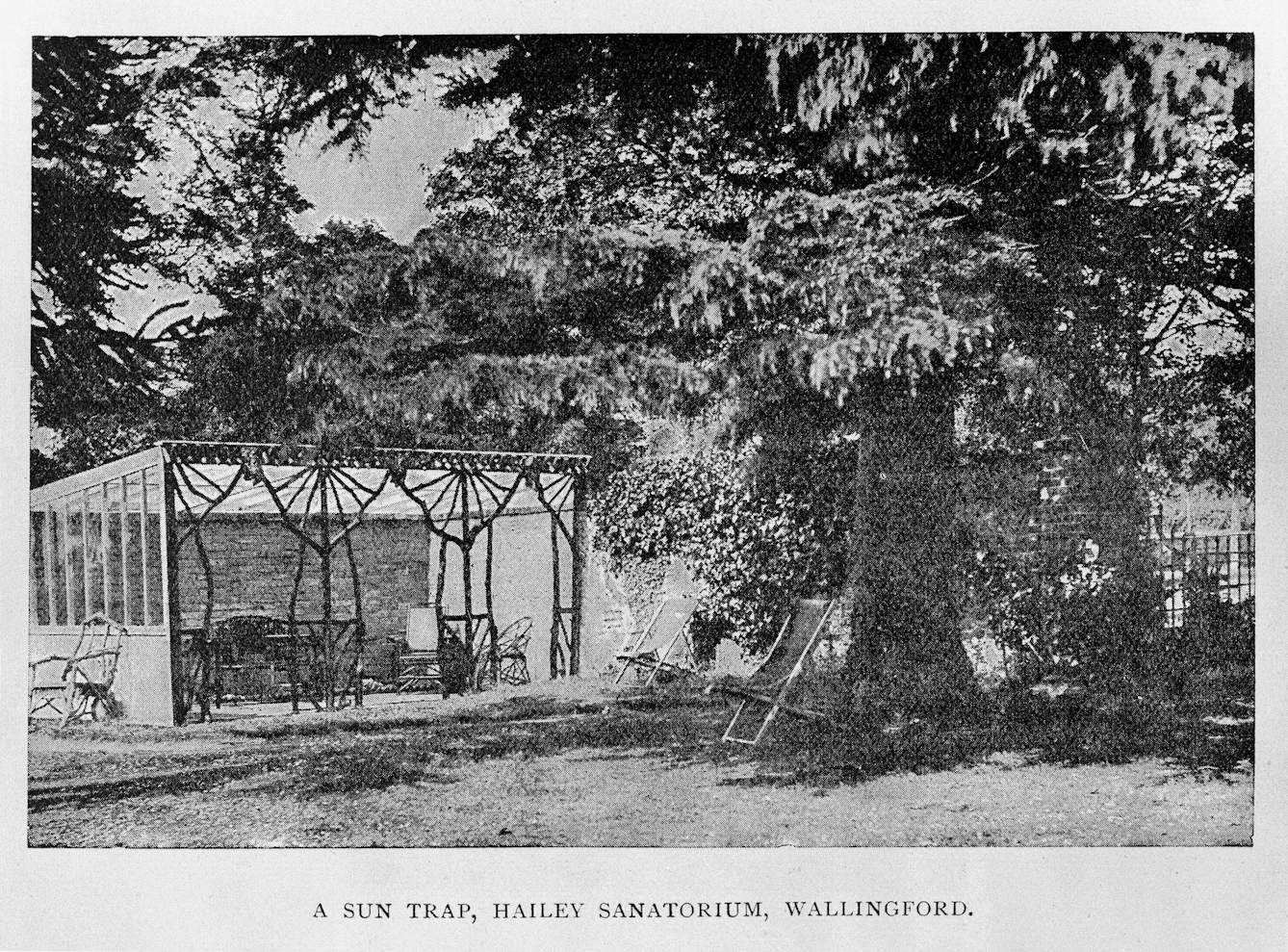

As the pace of industralisation increased across the UK, air pollution in towns and cities escalated. Less-affluent areas were (and are) more prone to lower-quality air, which significantly contributes to poor health. Those who could afford to ‘escape’ the bad air in the cities often visited luxury resorts where the air and water had health-giving properties. As well as treatments for the wealthy, air was a focus of treatment within TB sanatoriums.

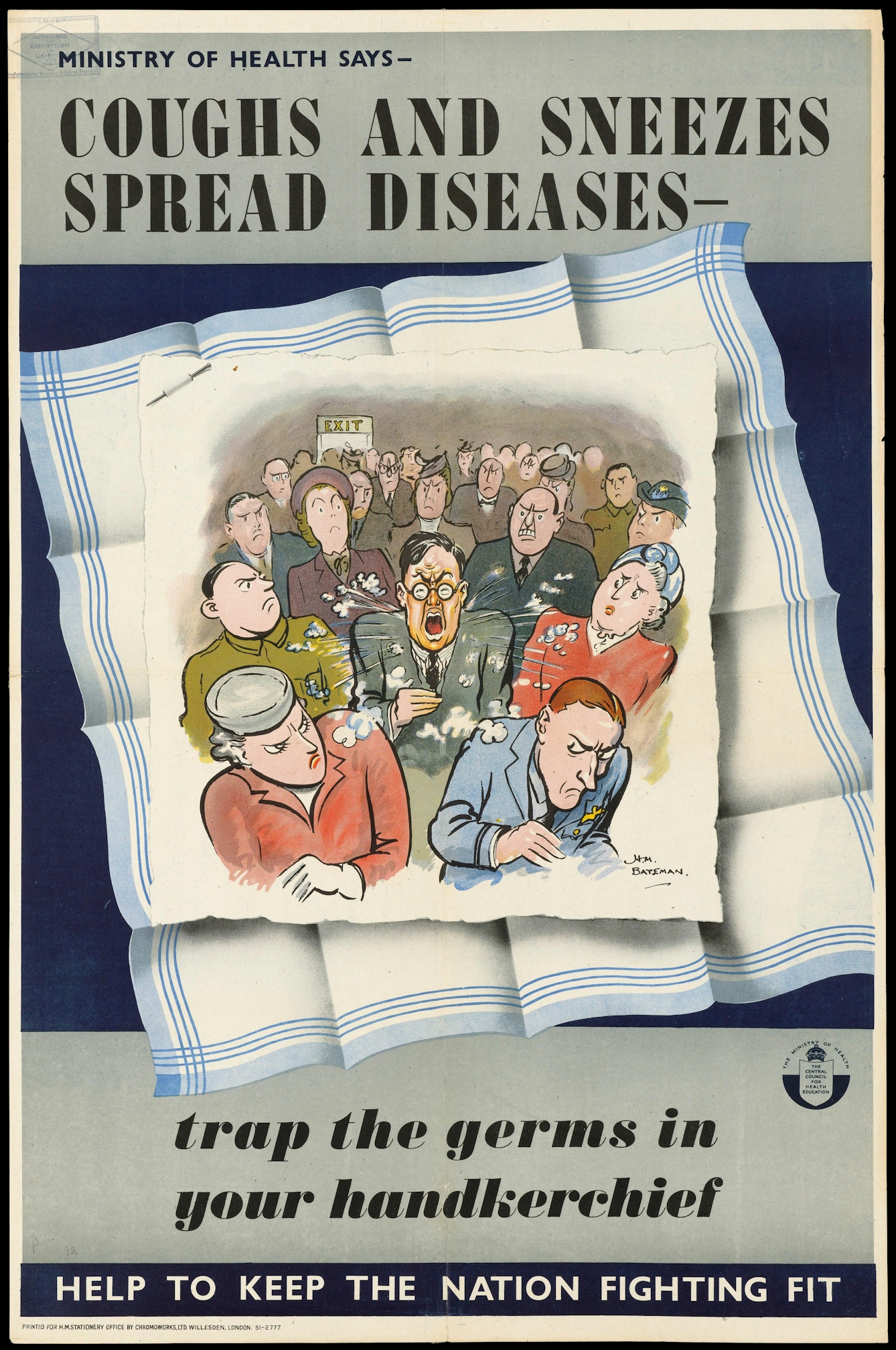

While germ theory became accepted, the idea of disease carried through coughs and sneezes became prominent in UK public health messaging, particularly after World War II. Adverts of the time aren’t so different from those we were used to seeing during the Covid pandemic, when we were encouraged to become hyper-aware of airborne disease transmission.

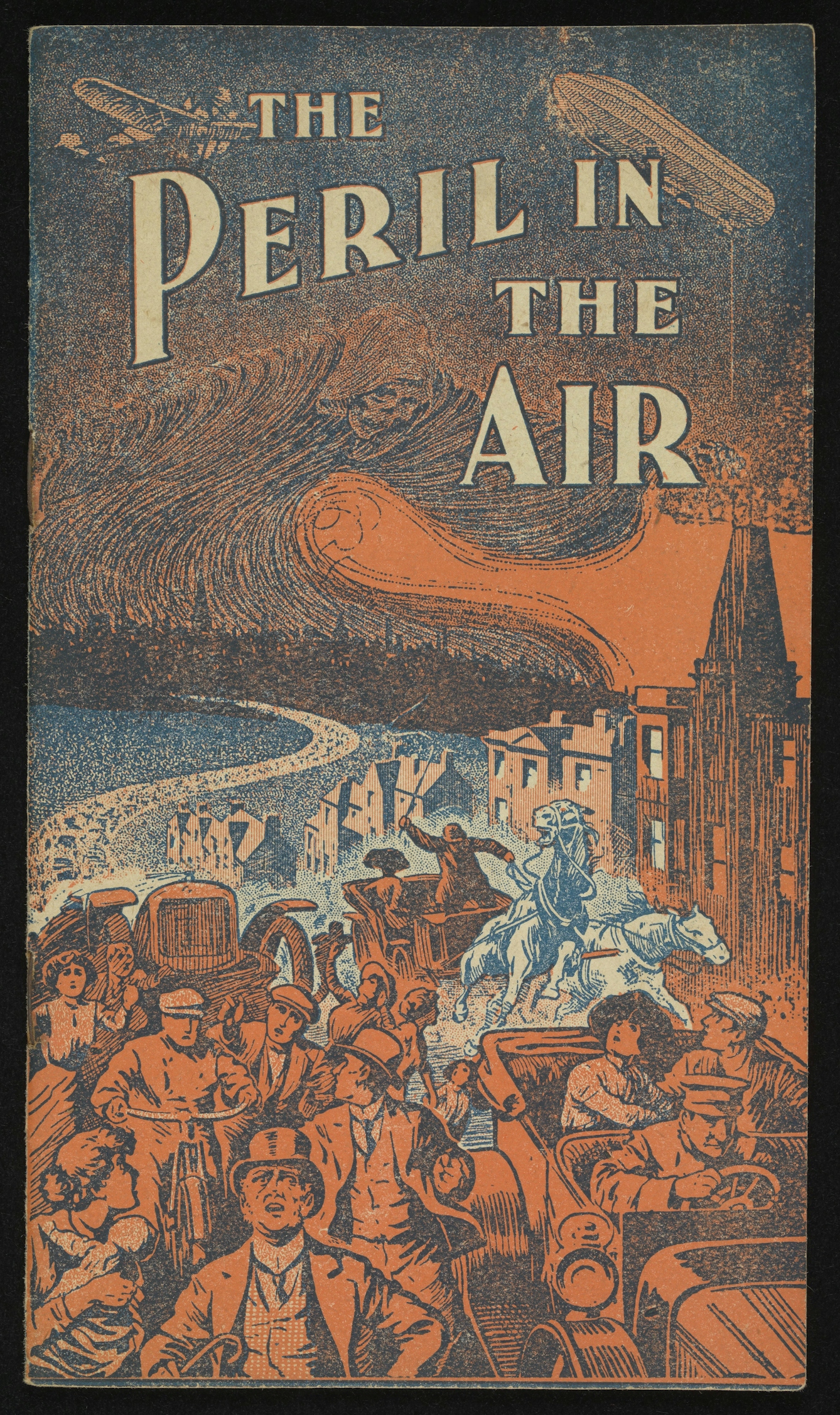

This distrust of the air we breathe is seen in promotional material for medication for respiratory complaints from the early 20th century. It captures an anxiety about the invisible enemy of airborne illness. Such materials stoke an idea of contagion and paranoia – every surface, every person breathing is a possible vector of disease, to be viewed with suspicion and mistrust. The germs travelling through the air in this advert are described as “worse than war” – an impossible conflict with an invisible enemy – although the product advertised promises to protect you by filtering “the foul or foggy, germ-laden air as it is breathed in”.

Some researchers have suggested that governments were slow to recognise the airborne transmission of Covid, even in the face of scientific evidence, because miasmatic ideas of disease were outdated compared to germ theory. The idea that a pandemic respiratory disease could spread through airborne transmission, as well as droplets in the air, felt archaic. Although our attitudes to public health have drastically shifted since the days of the plague fumigators, we are all still looking for ways to reduce our anxieties and protect ourselves from diseases in the air.

About the author

Kirsten Nicholson

Kirsten is a graduate trainee at Wellcome. Before this she studied at Glasgow School of Art.