No medical instrument, apart from maybe the dentist’s drill, incites more anxiety than the speculum, a medical instrument used to investigate body orifices. The vaginal speculum in particular confers on its bearer the right to access and control the female body in the most intimate way. Add that to the complex morality around sex, race and virginity, and the history of the speculum becomes very nasty indeed.

A nasty history of the vaginal speculum

Words by Lalita Kaplish

- In pictures

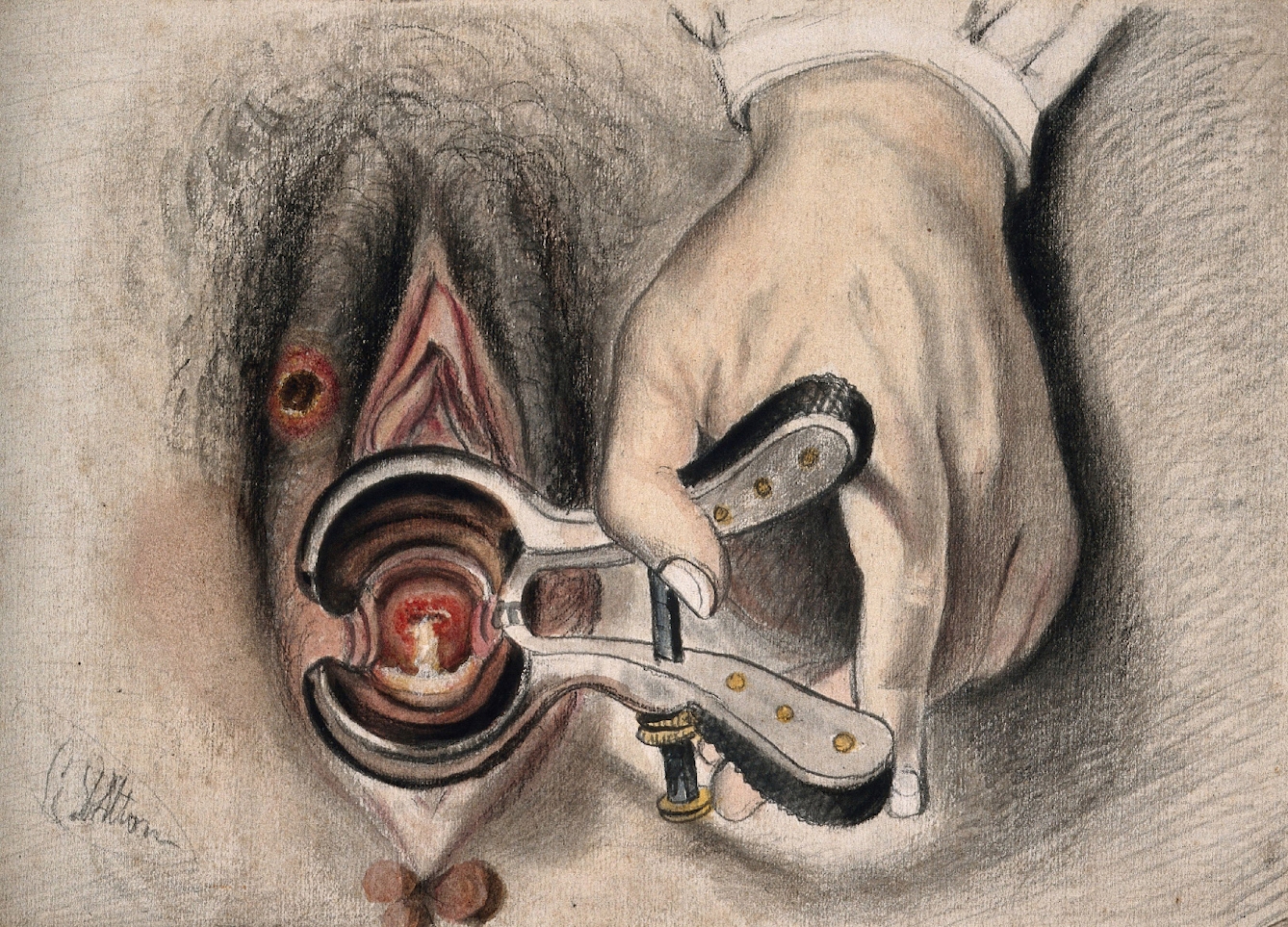

Vaginal and anal specula have been around for thousands of years. The ancient Greek rectal dilator (katopter) may originally have been two spoons, one held in each hand. A set of medical instruments found in the ruins of ancient Pompeii included what is thought to be a small vaginal speculum (or dioptrion), like the Roman copy seen here.

To inspect the vagina, the closed ‘blades’ of the instrument are inserted into the body and dilated using the screw mechanism, which leaves the operator with a free hand to hold another instrument. The blades are at right angles to the mechanism so that it’s easier to look straight through into the vaginal passage. This design changed very little for centuries.

Medics use specula to do examinations using the vagina as the point of access. For instance, the progress of a pregnancy can be followed using internal examinations of the vaginal passage. Medical examinations are used to identify signs of sexually transmitted infections, and issues with the menstrual cycle and fertility. And as most UK adults with a vagina aged 25 to 64 will be aware, the vaginal speculum is used for the cervical smear test, a regular check for cervical cancer.

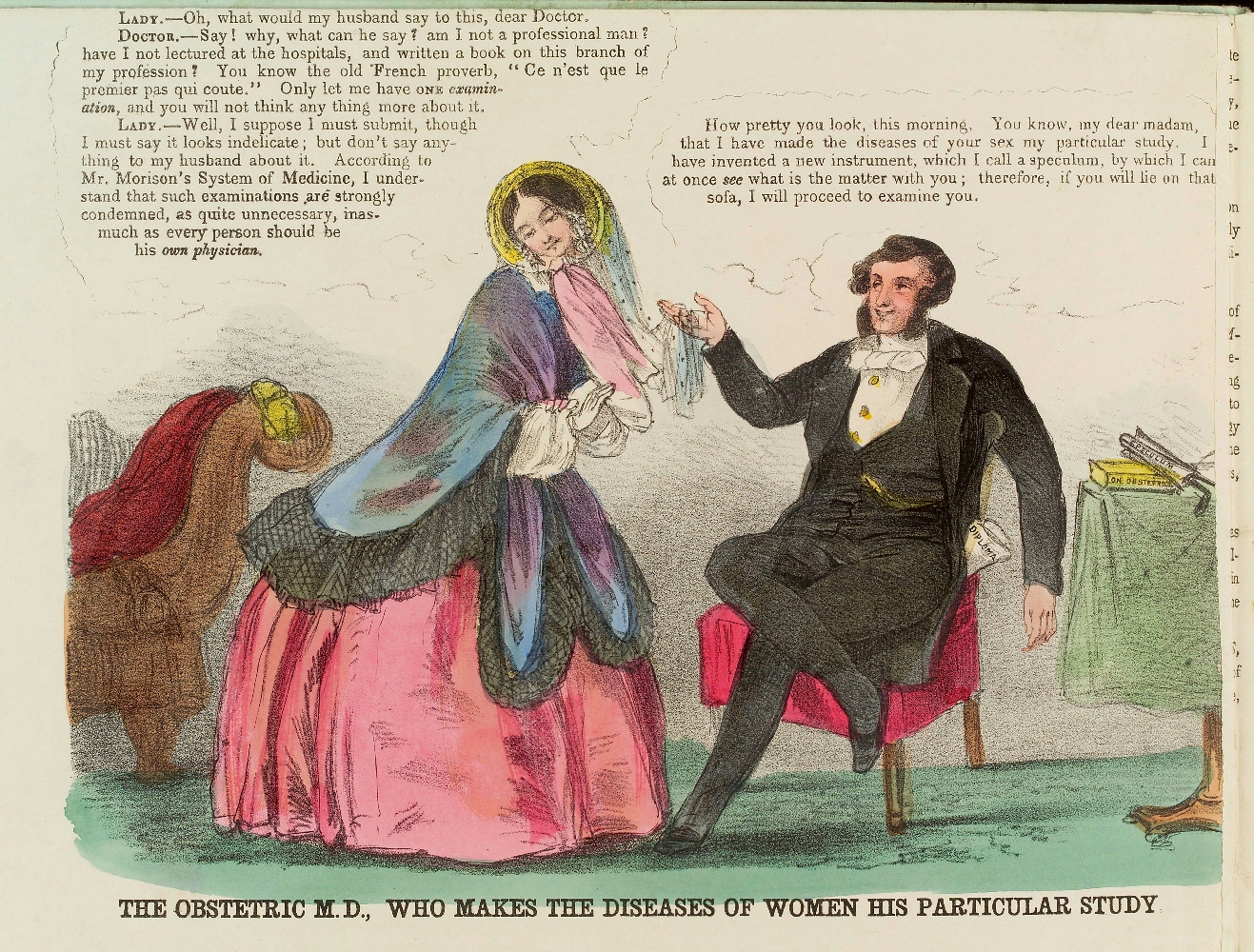

Until well into the 19th century, most gynaecological conditions were diagnosed by observing general symptoms or feeling the abdomen. Many physicians (and patients) feared that by penetrating the vagina, the speculum would tear the hymen covering its entrance, resulting in a loss of virginity.

Writing to the Lancet in 1850, physiologist Marshall Hall urged his colleagues to remember that “it is not mere exposure of the person, but the dulling of the edge of the virgin modesty, and the degradation of the pure minds, of the daughters of England, which are to be avoided”. In this caricature, the obstetric doctor flirting with his patient has a speculum on the table next to him, implying that both the doctor and the patient are guilty of sexual impropriety.

A 2022 article indicated that some medical examinations are still avoided due to concerns about hymens and virginity, a social construct widely dismissed by scientists.

While supposedly threatening to women’s morality, the speculum played a very different role in “safeguarding” Victorian men from the threat of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) – personified here as a skull-faced sex worker.

The British government passed three Contagious Diseases Acts (1864, 1866, 1869) to try to regulate prostitution and reduce STIs among the military in naval ports and garrison towns. Women suspected of being sex workers had to register with the police and receive a compulsory internal examination with a speculum.

The speculum and other instruments – sometimes not cleaned from one exam to the next – were inserted ineptly, and some women passed out from the pain or injury. Infected women were sent to a Lock Hospital until they were ‘clean’. In contrast to the squeamishness over vaginal examination for “respectable women”, there was little opposition to these practices against women who were generally poor and powerless.

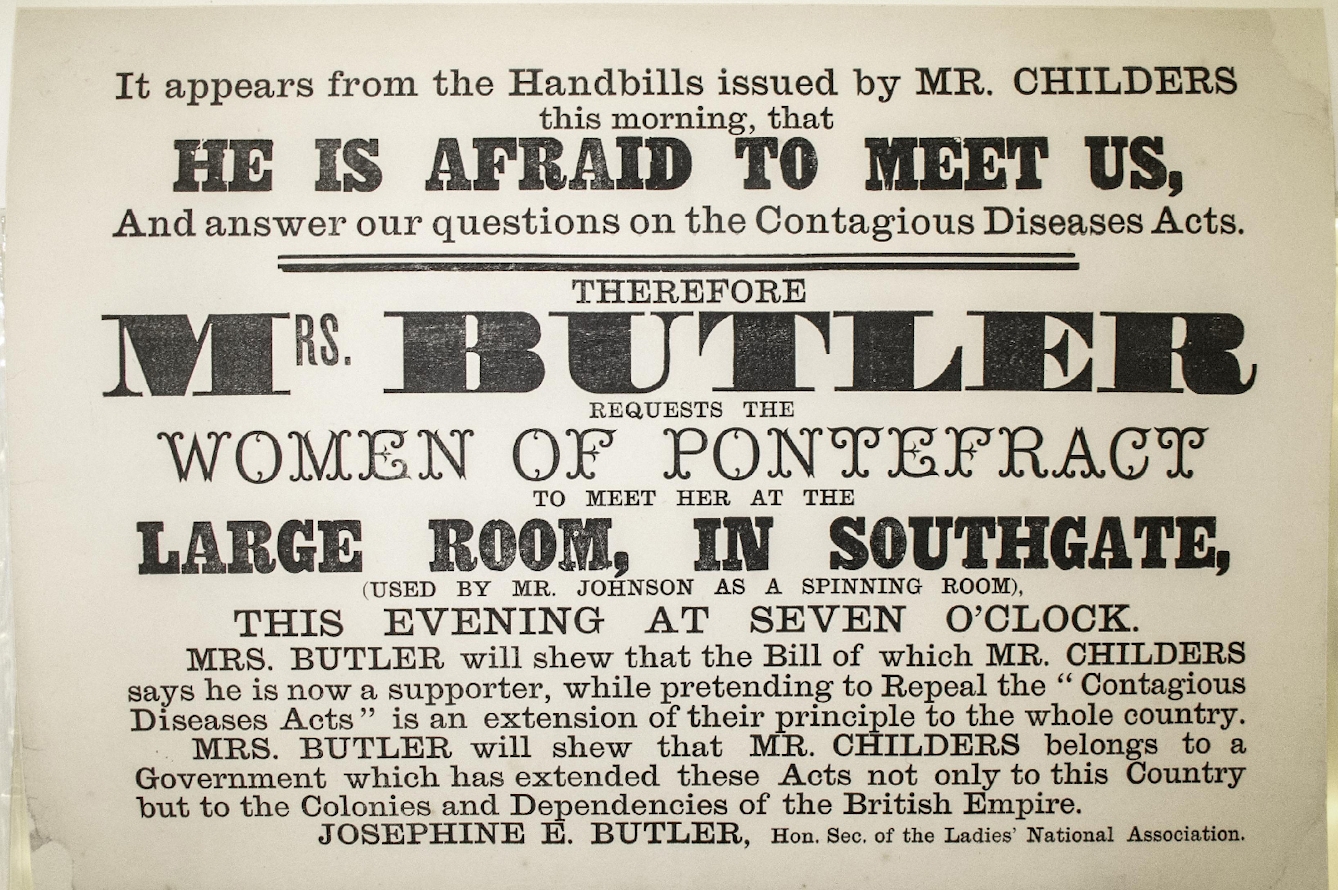

Many doctors refused to participate in the examinations. The Contagious Diseases Acts were finally repealed after 20 years of campaigning by women such as journalist Harriet Martineau, who attacked the Acts in her articles in the Daily News, and social reformer Josephine Butler, who started a grassroots crusade against the Acts.

As Butler observed in 1871: “Under the present Acts, a man whose infamous proposals have been rejected by a girl, may inform the police against her, and on his evidence the girl may be subjected to examination and ruined.” Butler rallied support among middle- and upper-class women by focusing on the constitutional rights of the women. By circulating hundreds of petitions framing the victimisation of these women as a class issue, she also garnered support from working-class men who had recently gained the vote.

The Acts were repealed in the UK in 1886 but remained on the statute books in British colonies. Laws remained in New Zealand until 1910. The practice continued in areas near British military stations in colonial India until Butler’s continued campaigning saw this, too, repealed.

The speculum changed very little over the centuries. Although some were wooden or bone to be less uncomfortable for the patient, most were made from metal. Metal was easy to clean, and once people became aware of germ theory from the 19th century, they knew also that metal was ideal for disinfecting with steam or chemicals.

Highly polished metal also reflected much-needed light during the examination. Indeed, one of the criticisms by physicians who mistrusted the speculum was that inserting the instrument into the vaginal canal could obscure lesions and other signs of infection – the very things they were looking for.

Some specula were designed for treatment rather than examination and had perforated blades or a cage-like construction that allowed for the absorption of ointments applied during examination. The Cusco speculum seen here was a standard design. It was a duckbilled bivalve instrument with a screw mechanism that held the two blades apart.

From the point of view of the patient, this cold device with its clanking metal did little to ease anxiety during what was already an intimate and embarrassing procedure.

Dr James Marion Sims (1813–83) invented the Sims speculum, shown here, which is still used today for vaginal surgery. Sims experimented with different instruments in the development of a surgical technique to repair vaginal fistulas. Fistulas are a complication of childbirth that occurred frequently in pre-20th-century Britain and continue to be common in many less wealthy countries. Vesicovaginal fistulas occur when the bladder, cervix and vagina become trapped between the baby’s head and the woman's pelvis, cutting off blood flow. The resulting dead tissue can leave a hole between the bladder and the vaginal canal, which causes a continuous stream of urine to leak from the vagina. Women with fistulas might experience skin irritation, scarring and loss of vaginal function, as well as the social stigma of incontinence. In a related condition, rectovaginal fistulas, flatulence and faeces escape through the damaged vagina.

Sims’ surgical technique was widely adopted along with his speculum, which was preferred, despite requiring an assistant to hold it open for gynaecological procedures, because it could slide around the vaginal wall, offering different viewpoints.

Sims conducted much of his research at his private hospital in the American South. From 1845 to 1849, he developed his techniques by doing experiments on enslaved Black women. In his autobiography Sims wrote of his proposition that if given Anarcha and Betsey "for experiment", he would not endanger their lives or charge their 'owners' for their keep.

He conducted experimental surgery on the women multiple times before the repair of their fistulas was successful, after which they were returned to their owners. The women were also trained to assist in their own surgical procedures, and with other women’s surgeries, often holding the speculum.

Sims did not use anaesthesia despite its ready availability, so the women often had to hold each other down as they writhed from the pain of being sliced and sutured.

It has been argued that Sims was a man of his time – a slave-owner in the American South – and behaved according to the standards of his day, but as writer Terri Kapsalis points out, "Sims' fame and wealth are as indebted to slavery and racism as they are to innovation, insight, and persistence, and he has left behind a frightening legacy of medical attitudes toward and treatments of women, particularly women of colour.”

The history of the speculum reveals a lot about the relationship between the doctor and the patient. The French philosopher Michel Foucault has talked about biopower: the power and authority conferred on the medical establishment and its representatives. In exchange for their knowledge and expertise and the promise of being healed, we give health workers access and control over our bodies and our lives.

And by lying on the examining table with legs splayed during a vaginal examination, we make ourselves vulnerable in more ways than one. I still recall a cervical smear test in my early 20s when the nurse commented as she was finishing up, “So you’re not a virgin, then.” In addition to the smear test, I had been given an unasked-for virginity test and experienced a humiliating invasion of my privacy.

The vaginal speculum has a nasty history, and the health worker who wields it brings to the vaginal examination the weight of generations of preconceptions about morality, blame and attitudes to pain. In the relationship between wielder of the speculum and the patient, the issue of control and presumed consent is key.

Simply holding the speculum does not confer complete control over the patient for the duration of the procedure. For the patient, who is submitting themselves for examination, it is all too easy to be coerced (however unconsciously) into accepting a greater level of intrusion, enduring greater levels of pain, losing control altogether. It’s important for both the practitioner and the patient to remember that nothing should happen in the examination without informed consent.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.