The history of selling sex is a hidden one – and too often its practitioners are pushed to the margins of history. In ‘Harlots, Whores & Hackabouts’, Kate Lister redresses the balance, revealing the history of the sex trade through the eyes of sex workers. In this extract, she argues why the way we write, think and talk about sex work matters.

A history of sex for sale

Words by Dr Kate Listerphotography by Steven Pocockaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Book extract

Stereotypes, stigma and sensationalism have obscured the lived experience of people selling sex throughout much of history. The stigma forced, and continues to force, many into silence, meaning the dominant social narrative around sex work has been constructed and deployed by law makers, moralisers, medics and the media. Stereotypes of the unrepentant, titillating whore or the tragic victim in need of rescue have long stifled the voices of those who sold sex.

The very nature of sex work is, and has always been, to sell a fantasy. When we watch porn, for example, we see only the carefully choreographed final product. We see the actors, the set and the make-believe sex. We do not see the camera crew standing around and eating sandwiches, the multiple takes, the fake cum or the discussions around consent and boundaries. The fantasy is the finished product, but it is never the whole story.

Sex work is, and has always been, a highly complex experience that resists easy definition. From the temple whores of Babylon and the legendary courtesans of ancient Greece, to the hustling molly boys of Georgian London, the lob-lob girls of Canton, and the Winchester Geese trading on medieval London’s Gropecunt Lane, there is no one version of sex work: there are legion. Some made their name trading sex for fabulous sums of money, others occasionally turned to sex work to supplement a low wage: a side hustle once known as ‘dollymopping’.

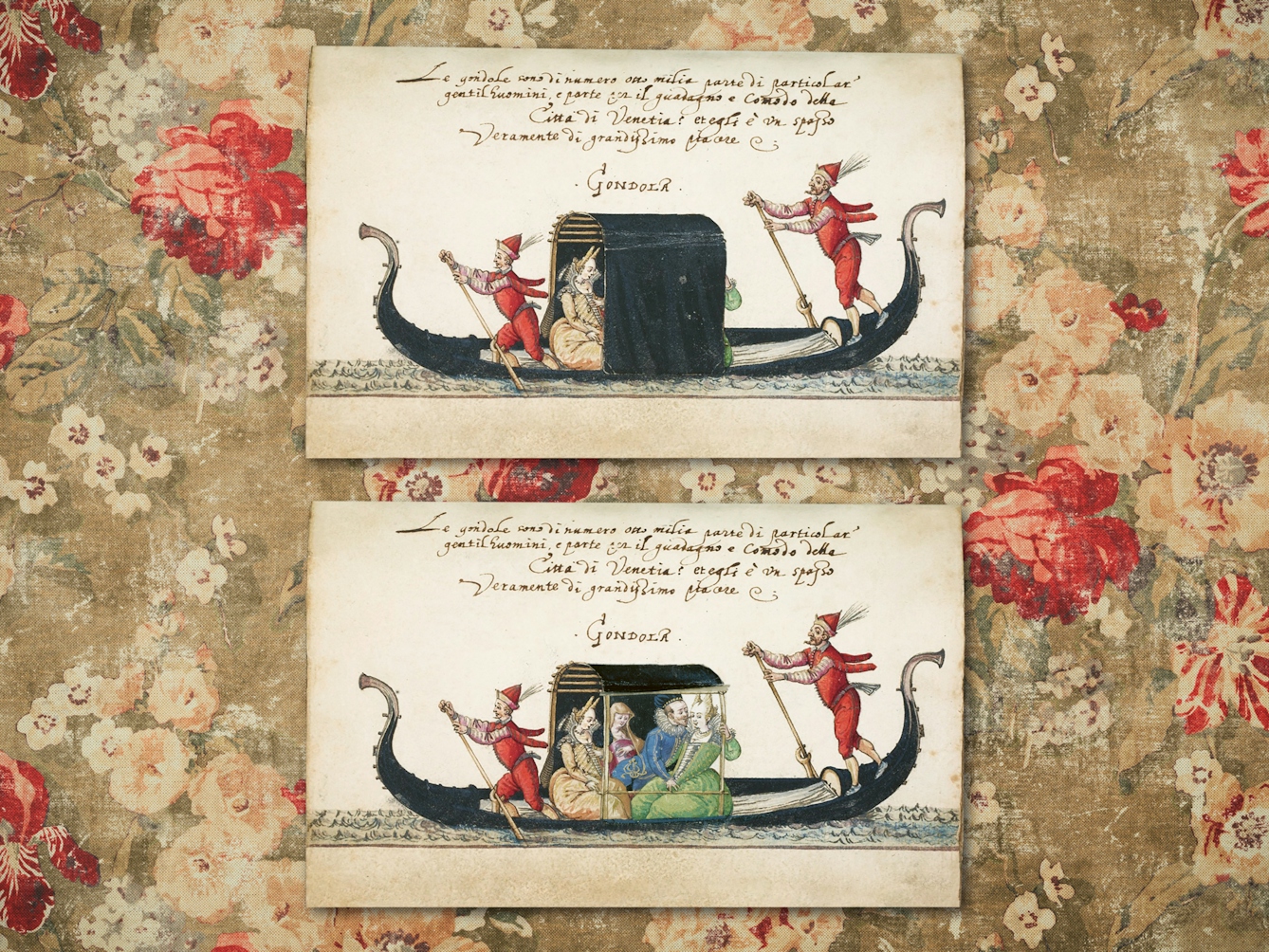

Selling sex in Renaissance Italy

Any woman wanting to sell sex in the major cities of Renaissance Italy could expect to be registered with the state, licensed, taxed and restricted to official zones. She was subjected to laws that governed what she could wear, where she could go and where she could live

Legalisation did not mean acceptance, and a sex worker could be expected to be marked out from a donna onesta (honourable woman). For example, in 1384, Florence passed sumptuary laws that required its meretrici to wear bells on their heads, gloves and towering platformed shoes, known as chopins.

In Mantua and Parma, sex workers were ordered to wear a white cloak in public. In Milan, the cloak was black, and in Ferrara, Bergamo and Venice it was yellow. Any woman caught flouting the laws was subject to punishments ranging from a fine and a night in the cells, to being paraded nude throughout the city streets while mobs hurled rotten food.

Many cities introduced strict zoning policies and state-owned brothels where transactional sex could take place. In Venice, the brothel area was called the Castelletto, or the small castle, and was accessed via ‘Tits Bridge’. To get there, clients had to cross the Grand Canal to a ferry point known as the traghetto del buso, or ‘the crossing of the hole’.

Many who sold sex lived, and continue to live, in terrible poverty, and choose full bellies over empty platitudes of morality. Then there are those who did not choose at all but lived in sexual slavery. All traded fantasy and sexual favours, and all faced varying levels of abuse and social stigma.

Quite how much stigma various groups have shouldered has historically been dictated by money and class – the wealthier the client, the less stigma involved. The glamorous, diamond-studded courtesans and professional mistresses of the medieval and Renaissance European aristocracy, for example, not only commanded respect, but many wielded considerable political influence over their besotted clients. Royal mistresses were so powerful, many were referred to as the “power behind the throne”.

Throughout history, authorities have fretted about how to best ‘deal’ with those who want to buy or sell sex, moving through various stages of repression, toleration, legalisation, control, moral outrage and abolition, before circling back again.

History is littered with various efforts to prevent sexual exploitation by abolishing sex work. None of them have worked.

History is littered with various efforts to prevent sexual exploitation by abolishing sex work. None of them have worked. Torture, mutilation, fines, imprisonment, banishment, excommunication and even the death penalty have all been deployed at various points, and none have succeeded in abolishing the sale of sex. Nor have these punitive measures ended sexual abuse.

All that happens is consenting sex workers are forced to work in dangerous conditions and are further stigmatised for what they do, and those who are abused become even harder to find.

The floating world of Edo Japan

The establishment of designated pleasure quarters in the Edo period facilitated widespread acceptance of sex work within Japanese culture. Yūkaku became worlds within worlds, where order and control could be left at the gates for a short time and a hefty price.

The two most famous yūkaku in Edo Japan were Yoshiwara in Edo (present-day Tokyo) and Yanagimachi in Kyoto. Writing in 1661, Asai Ryōi called the yūkaku ‘ukiyo’ or ‘floating worlds’. Ukiyo-e were woodblock prints that depicted life in the pleasure quarter: the courtesans, their clients and later the geishas who flourished in the floating world.

The word ‘geisha’ translates to ‘artist’, and although great pains are taken to distance the modern geisha from sex work, there is no denying their shared history. Artist or not, the geisha was born in the pleasure quarters of Edo Japan.

The men who flocked to the floating worlds were seduced by the glamour and heady sensuality they offered, but the reality for most of the people who worked there was very different. The courtesans, actors and kagema (male sex workers) were certainly very beautiful, but few were free to live their own lives.

One of the central mantras of the modern-day sex worker rights movement is ‘Stigma Kills’, and with good reason. In 2000, Canadian professor John Lowman analysed descriptions in the media of efforts to abolish sex work by politicians, police and local residents, and identified a “discourse of disposability”. Lowman linked this with a sharp increase in the murders of street sex workers in British Columbia, Canada, after 1980.

He argued that, “It appears that the discourse on prostitution of the early 1980s was dominated by demands to get rid of prostitutes from the streets, creating a social milieu in which violence against prostitutes could flourish.”

This is how stigma works. Once the sex worker is stigmatised as ‘less than’, or ‘disposable’, a message formed, shaped and deployed in debates around morality and abolition, this discourse then influences how sex workers are treated. We can see this rhetoric at work throughout history. Draconian laws and harsh punishments against those selling sex reinforce social stigma, which enables violence to flourish.

My book ‘Harlots, Whores & Hackabouts’ uncovers the history of people who have bought and sold sex, but abolishing the ongoing stigma around sex work is everyone’s responsibility.

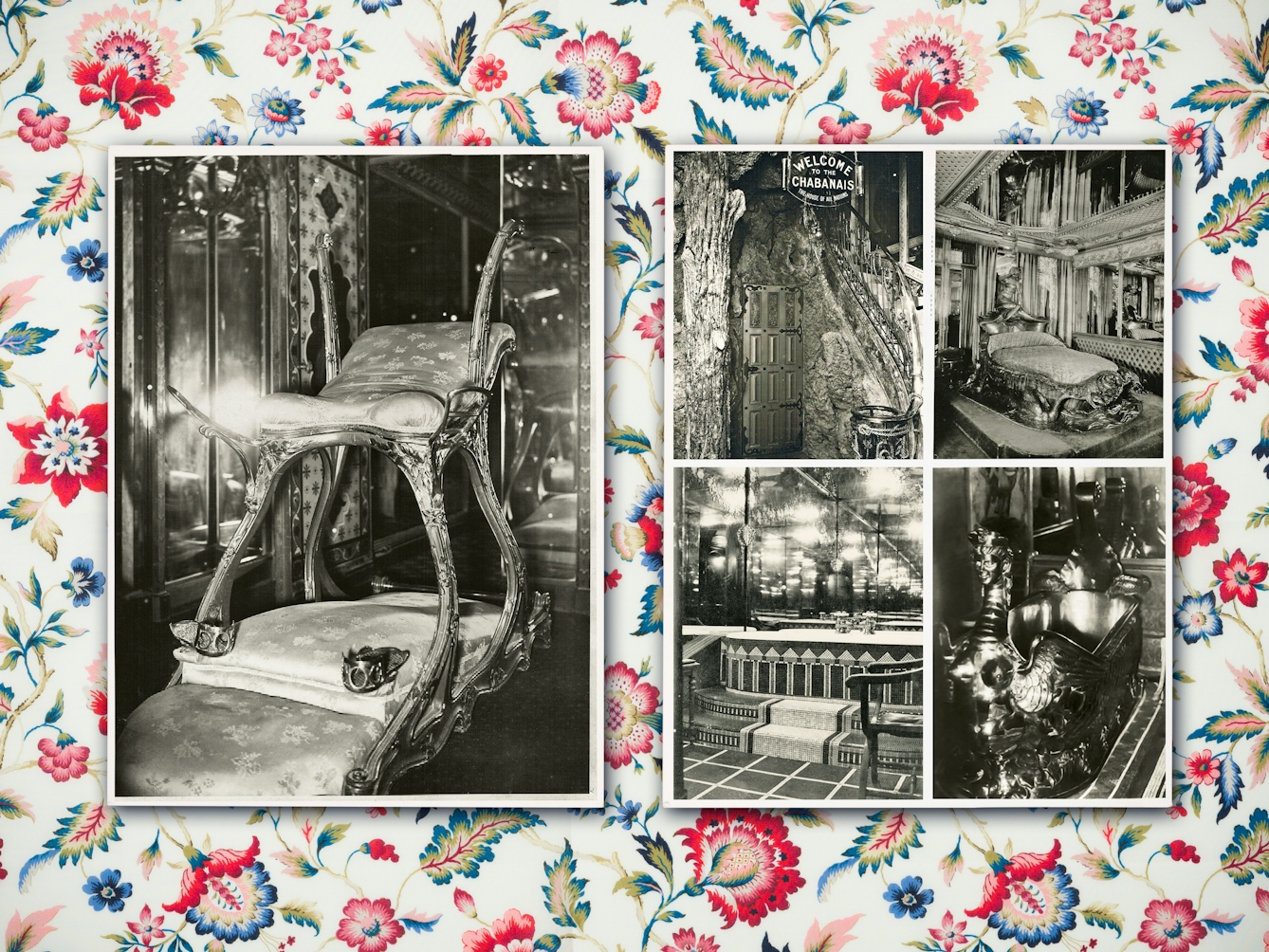

Maisons de tolérance and the Belle Époque

The French government introduced a system of state-regulated prostitution in 1802. Brothels, or maisons de tolérance, became a common sight in Paris, but no one had seen anything like Le Chabanais before. Lavish and luxurious, its patrons included Guy de Maupassant, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart and Mae West.

Albert, the Prince of Wales and future King Edward VII, had his own suite. It boasted an ornate copper bath, decorated with a bare-breasted woman, where the prince and his lovers would bathe in champagne, and a siège d’amour, or ‘seat of love’, designed by Louis Soubrier, which allowed him to enjoy two partners at once, as well as supporting his bulk.

Legalised, state-regulated prostitution strictly controlled where and when women could work. France’s budget brothels were commonly known as maisons d’abattage, or ‘slaughterhouses’. A special 1939 edition of Le Crapouillot counted 12 in Paris, including Le Moulin Galant on rue de Fourcy. It employed 60 women and charged a flat rate of five francs and 50 sous – the 50 sous were for the use of a towel.

These ‘slaughterhouses’ were a world away from the glitz and glamour of Le Chabanais. The women who worked in them were invariably poor and frequently subjected to abuse, not only from clients but from the police who enforced the regulations they had to abide by.

It is said that sex work is the world’s oldest profession, but this is not true. In cultures without money, there were no professions at all and little evidence of prostitution – though, doubtless, sex has always been a useful commodity in one way or another.

It was Rudyard Kipling who first coined the phrase “the world’s oldest profession” in his short story ‘On the City Wall’ (1898). The tale opens with the immortal line: “Lalun is a member of the most ancient profession in the world.” The expression has since fallen into common parlance as a historical truth.

But perhaps what Kipling wrote after those words offers even more insight into what is, at least, a very ancient profession indeed: “In the West, people say rude things about Lalun’s profession, and write lectures about it, and distribute the lectures to young persons in order that Morality may be preserved.”

How we write about sex work, indeed how we think and talk about it, matters. It might not be the ‘oldest’, but it is a very ancient one. Its workers are deserving of rights and respect, of being genuinely heard and seen, rather than stereotyped and silenced. It is time to move beyond the fantasy. It is time to look, listen and learn.

‘Harlots, Whores & Hackabouts’ is out now.

About the contributors

Dr Kate Lister

Kate Lister is the creator of the award-winning online research project Whores of Yore, which seeks to build public engagement and disseminate research on the history of sex and sexuality through social media. She also lectures at Leeds Trinity University, and is widely published on the sex trade.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.