When poet Nina Mingya Powles moved to Britain, she felt acute homesickness for her previous homes in New Zealand and Shanghai. As she planted a garden and began keeping a diary of her plants, she rooted to her new home by cultivating the scents and sights of her childhood.

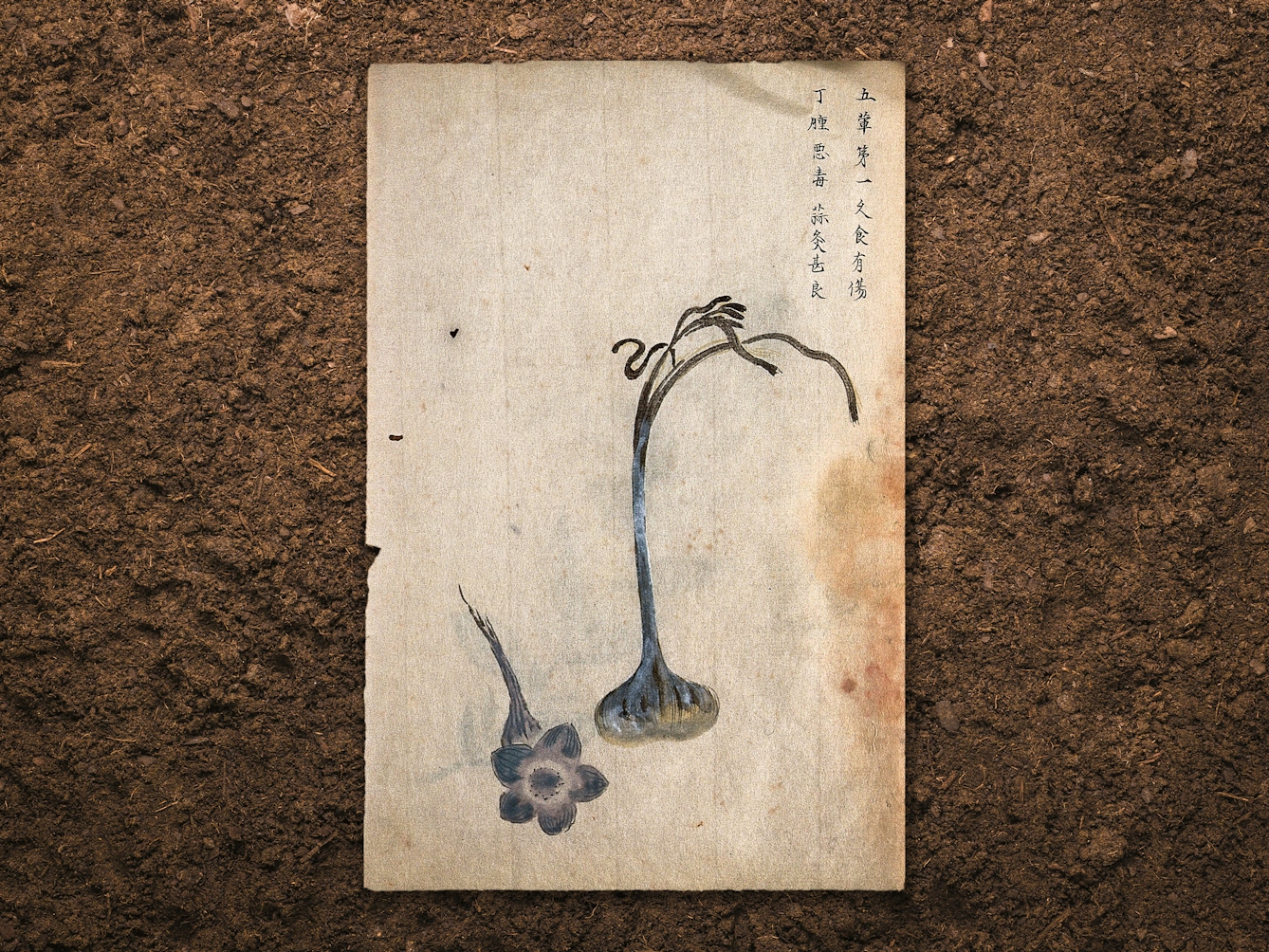

姜、蒜、葱 Ginger, garlic and spring onions

Words by Nina Mingya Powlesartwork by Faye Helleraverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

1 March

Here: first day of spring. Back home: first day of autumn. Today I feel a shift within me. I move a dormant orchid into the light. I fill a bowl with compost and plant two pieces of ginger, dampening the soil and placing it near the radiator.

I am forever between two seasons. Having grown up in several countries, I’m used to feeling rootless, drifting. I am the daughter of an immigrant; maybe it’s in my blood.

Two years ago I moved with my partner to a flat with a small balcony overlooking the Overground rail line in north London. I’d been living in London for six months, and although it was an exhilarating place to live, I often felt weighed down by homesickness and anxiety, in the form of dreams and intrusive thoughts of oncoming disasters.

Until moving to the UK, I’d never experienced overt racism, since although I’m mixed race, I often pass as white. There was a series of casual interactions: a racist joke made by an acquaintance over drinks, at a barbecue, in an ice-cream shop. I was caught off guard.

Afterwards I felt like I was floating, like I was not really there. In these moments I wondered what I was really doing here, and if I could ever feel rooted to this place.

I missed the sound and smell of the sea; Wellington, the city in New Zealand where I was born, curves around a shimmering blue harbour. I missed the trees in my parents’ garden: lemon, feijoa, pōhutukawa, kōwhai. Dad collected bags of wind-dried mussel shells from the beach to use as mulch under the flax bushes. Mum planted salt-loving succulents along the borders.

Lemon (Citrus limon).

A year and a half later, the expiry date on my visa was looming. I still didn’t have many friends in London, and I wasn’t sure if I could ever feel like I belonged here. But my parents had moved away from Wellington, so the threads connecting me to that other place suddenly felt just as fragile, breakable. I stayed in London.

Planting a garden roots you to a place in a deep, physical way. The garden’s existence, however small, depends on you. After a while you begin to depend on it, too. I’d always been scared of putting down roots, having had to pull them up so many times before. Slowly, I began to learn.

I read online about how to sow seeds in pots. I watched videos about how to plant and uplift winter bulbs, how to re-pot shrubs and tie stems. On my shady balcony, I began planting a garden. I wrote down everything: what I’d planted and where, lists of seeds to buy, the shifting patterns of sunlight and shade across my balcony as the days lengthened.

More sensible gardeners would start with plants that most suit the microclimate of their space. Instead, I started a project to bring the tastes and smells of home to my flat in London. I planted the holy trinity of seasonings in Chinese cooking: ginger, garlic and spring onions.

Garlic (Allium sativum).

6 March

I wake to purple crocuses and daffodils on the windowsill. Little else grows yet except white-flowering weeds and spring onions shooting up since the last frost. In the afternoon a box arrives: my new kōwhai sapling. I hold my face close to its tender branches. The kōwhai’s leaves smell like mint and citrus.

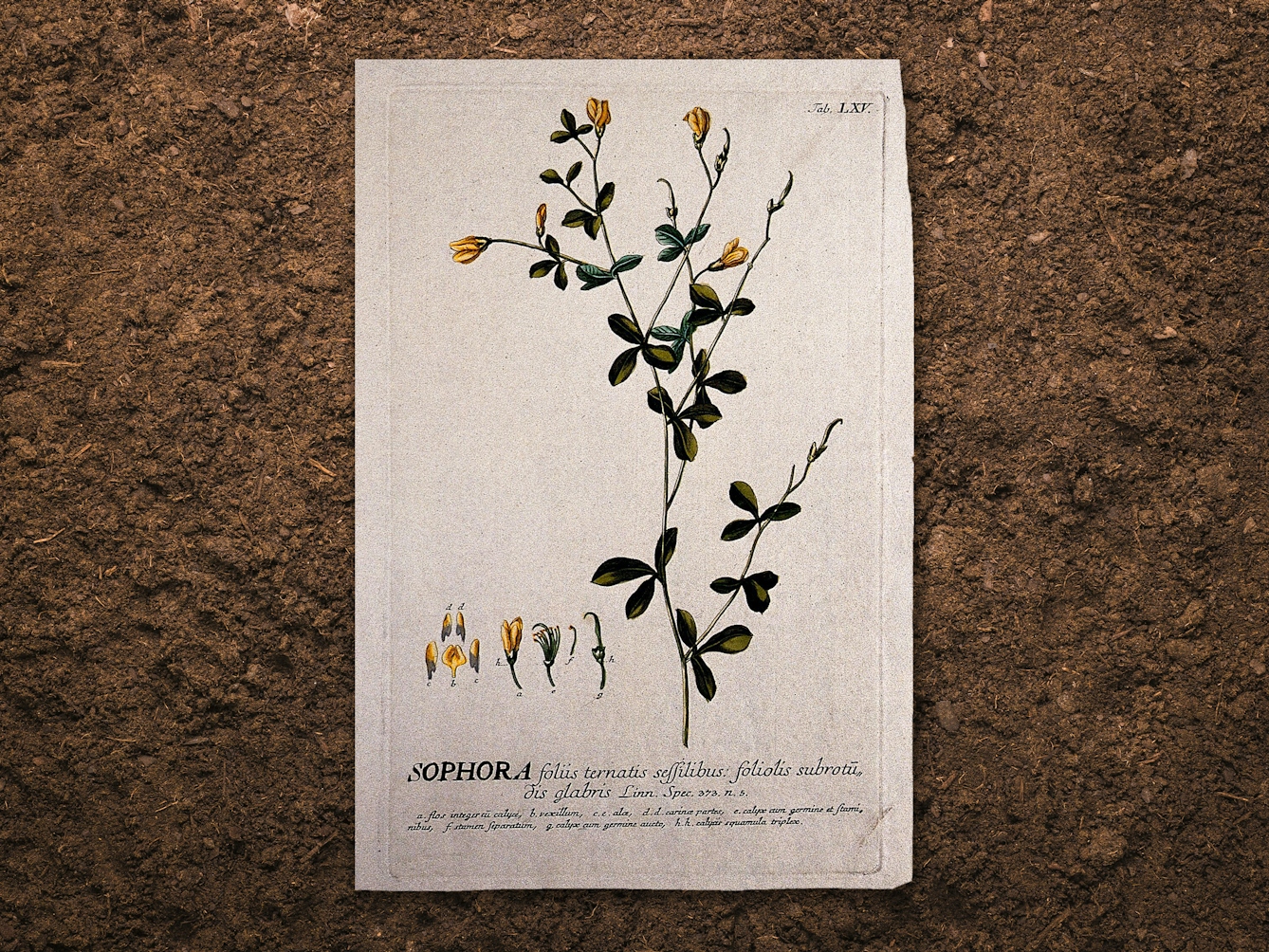

Sophora microphylla is a species of kōwhai tree – its yellow blooms being, unofficially, the national flower of Aotearoa New Zealand – that grows small enough to live in a pot. To my astonishment, it’s a common garden shrub in Britain, on the other side of the world. In 1774 botanist Joseph Banks collected kōwhai and other native plant specimens from Aotearoa and brought them back to England. A kōwhai descended from these seeds now grows at Chelsea Physic Garden.

Sophora (Sophora tinctoria), a plant related to the pagoda tree.

I emailed my aunt, who lives in Canada and is a keen gardener, for advice on growing lemongrass. She wrote back telling me to soak the roots in a jar of water. In three days, root tendrils began to sprout.

The lingering heat of ginger pulls me back to my mum’s chicken broth simmering for hours on the stove. Each week I cut away pieces of lemongrass root and pull up clumped ginger rhizomes. I slice and mince these into a sambal paste for my aunt’s curry recipe. Powdered turmeric stains my fingers the colour of the innermost cup of a daffodil.

Ginger (Zingiber zerumbet).

10 March

Crocuses sink and fade like deflated balloons. My wild-looking lemongrass, which I thought was dying, has sprouted a new shoot overnight. After its first night outdoors, my kōwhai is still alive. It may be stronger than it looks.

What started as a March gardening diary turned into an isolation diary, as the world went into lockdown and countries shut their borders due to Covid-19. I busied myself sowing seeds to distract from the worry of not being able to fly home in an emergency, and of still having to go to work in a dense area of the city.

I’m far luckier than many: I have a small outdoor space, now more precious to me than ever. Everything about the future is uncertain, but I’ve still been planting wildflowers and sunflowers – gifts to summon the bees, come summer.

17 March

I notice the dried-up marigolds have seed heads tightly packed with dozens of seeds. I’d left them to fade and was about to throw them away. While the world is shutting down around me, I cut the flower-heart husks and scrape seeds from their shells, tipping them into paper envelopes to post to friends in isolation.

Three ornamental yellow flowers, including a French marigold (Tagetes patula).

Gardening, I focus on the physicality of plants: their shapes, colours and textures at different stages in their life cycles, the scent they leave on my fingers. My small garden is starting to show me a way of tying myself to this place, this new home where I never thought I would feel grounded. In tending the plants, I learn to become more tender with myself.

23 March

Today, the seedlings sprouted. Today, both Britain and New Zealand are going into lockdown. My eyes ache; I haven’t been sleeping. At 05.00 I receive a WeChat message from Mum with a link attached: ‘Best Plants for Container Gardens’. Hydrangea, lavender, azalea, it says. Together their names sound like a spell. I think of her blue hydrangeas shaking in the wind, her lavender by the postbox. I will plant lavender next.

About the contributors

Nina Mingya Powles

Nina Mingya Powles is a poet and zinemaker from Aotearoa New Zealand, currently living in London. She is the author of ‘Magnolia 木蘭’, shortlisted for the 2021 Ondaatje Prize and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, and a food memoir, ‘Tiny Moons’. In 2019 she founded Bitter Melon, a small press dedicated to publishing limited-edition poetry pamphlets by Asian authors. Her debut essay collection, ‘Small Bodies of Water’, was published in 2021.

Faye Heller

Faye Heller studied for her MA in Fine Art at the Slade School, University College London, UK and is a qualified teacher. She has been making artwork for over 25 years and her work was shown at the Tate Modern on a late night for the Dora Maar exhibition in 2020. Using handmade photomontage and collage, she combines portraiture with the natural and man-made landscape, exploring the psychological and environmental, and evoking layers of time, landscape, places and encounters.