As new buildings rise in the Somers Town area of London, close to Wellcome Collection, site workers unearth remnants of the dairies that once served the local population. Esther Leslie traces the area’s milky history, from cow pastures to rapid urbanisation, and from milk adulteration to the 20th-century emphasis on the health benefits of dairy products.

Not far from Wellcome Collection, across the Euston Road in Somers Town, building projects uncover forgotten things as demolition takes place. An old supermarket on Chalton Street is redeveloped as a hotel. As the contractors clear out the remains of the store, older things come to light. In the basement, they find glass milk bottles from the grocer’s that once occupied the site, and some animal teeth, still in a jaw; a few oyster shells; and a trough.

The trough is roughly cut from a block of heavy stone and difficult to move. It is offered to the small museum that has recently opened to document a many-layered and kaleidoscopic history of the area. Enquiries among the older people who have lived here for more than 80 years reveal it to be the drinking trough that could once be seen from Churchway, the alleyway beside the store. Here the horses supped, after pulling milk in glass bottles around the nearby streets. It is just one part of the history of milk in the area.

So much milk once flowed through the streets of Somers Town. Until the 1860s, suburban dairies were tucked behind the 19th-century housing, and pasture-land supported herds of up to 100. The cows drank and excreted by the Fleet River and in Marylebone’s fields – the best grasslands were in the north and north-west of London. Cattle wintered in stalls or basements. Milk from the urban dairies could be bought warm from the udder and consumers might have seen the cow that fed them.

But there was not enough milk to feed the needs of a growing city, and Charles Dickens, resident as a child in Somers Town and never able to shake its destitution off – as his fiction attests – wrote about milk dilution and adulteration. ‘The Cow With the Iron Tail’, from 1850, describes a pump in High Holborn whose cholera-carrying water is added to milk by dairymen, and this from cows, who, Dickens insists, would kick over pails if they perceived their milk to be mixed with other cows’ milk.

To disguise the milk’s thinness, Dickens claims that flour, starch and mashed calves’ brains are added, and chalk to whiten, and, “lastly, they go to a secret doctor’s and buy a set of dusky orange-red balls, made of mysterious stuff, which, being well worked round, melts gradually, and gives the nice yellowish tint what’s wanted”. To get a good froth, snails are thrown in, stirred around and then strained off.

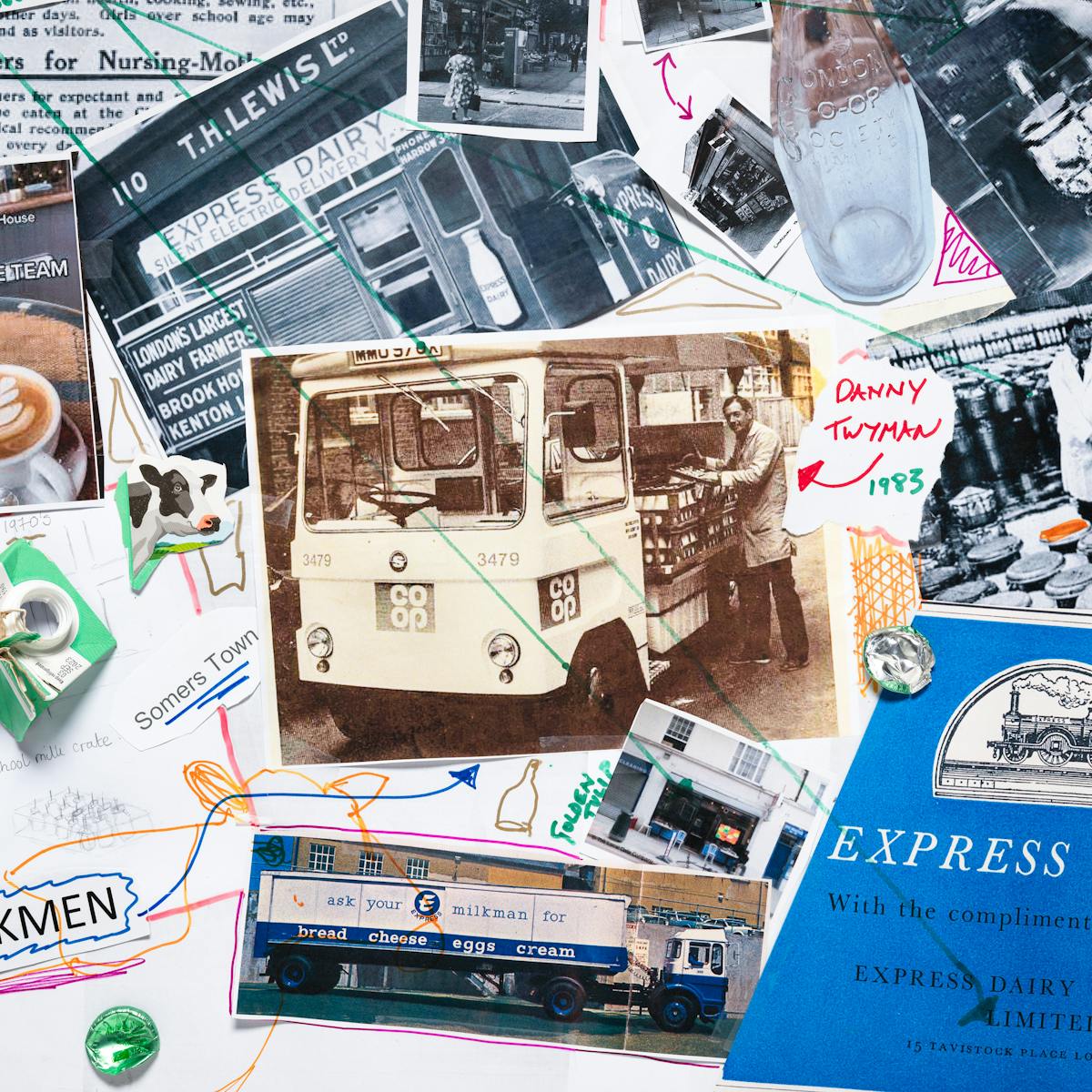

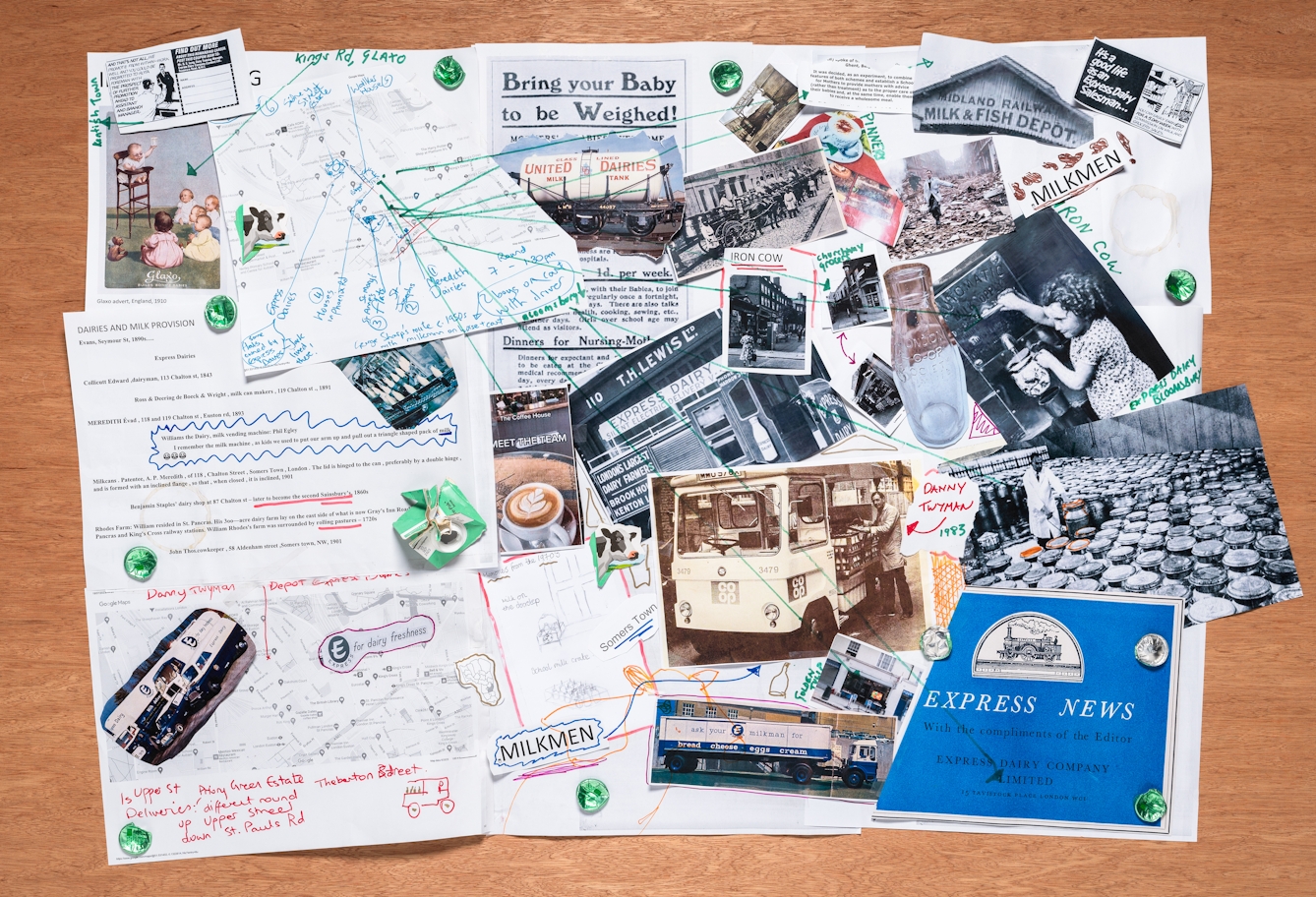

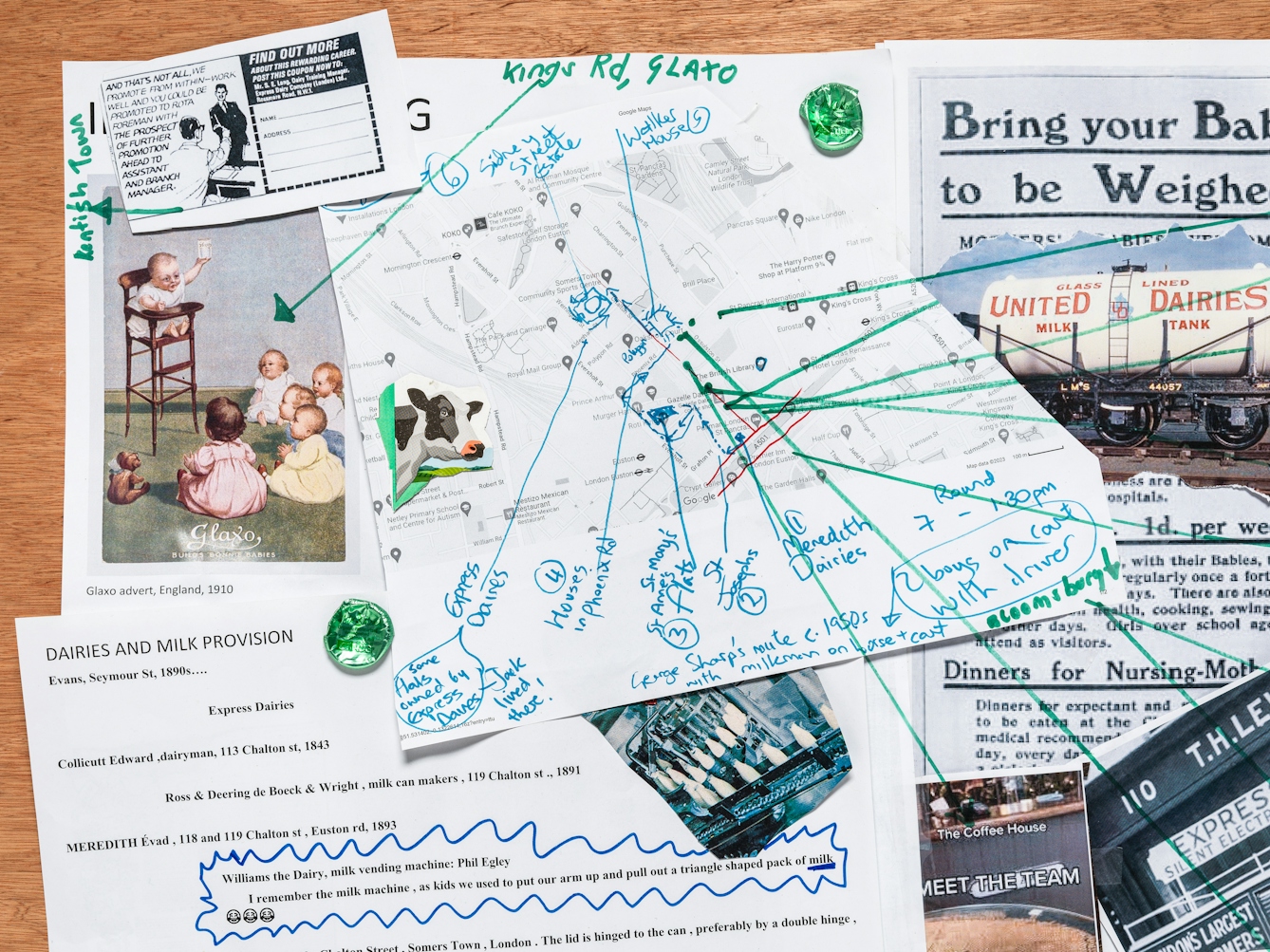

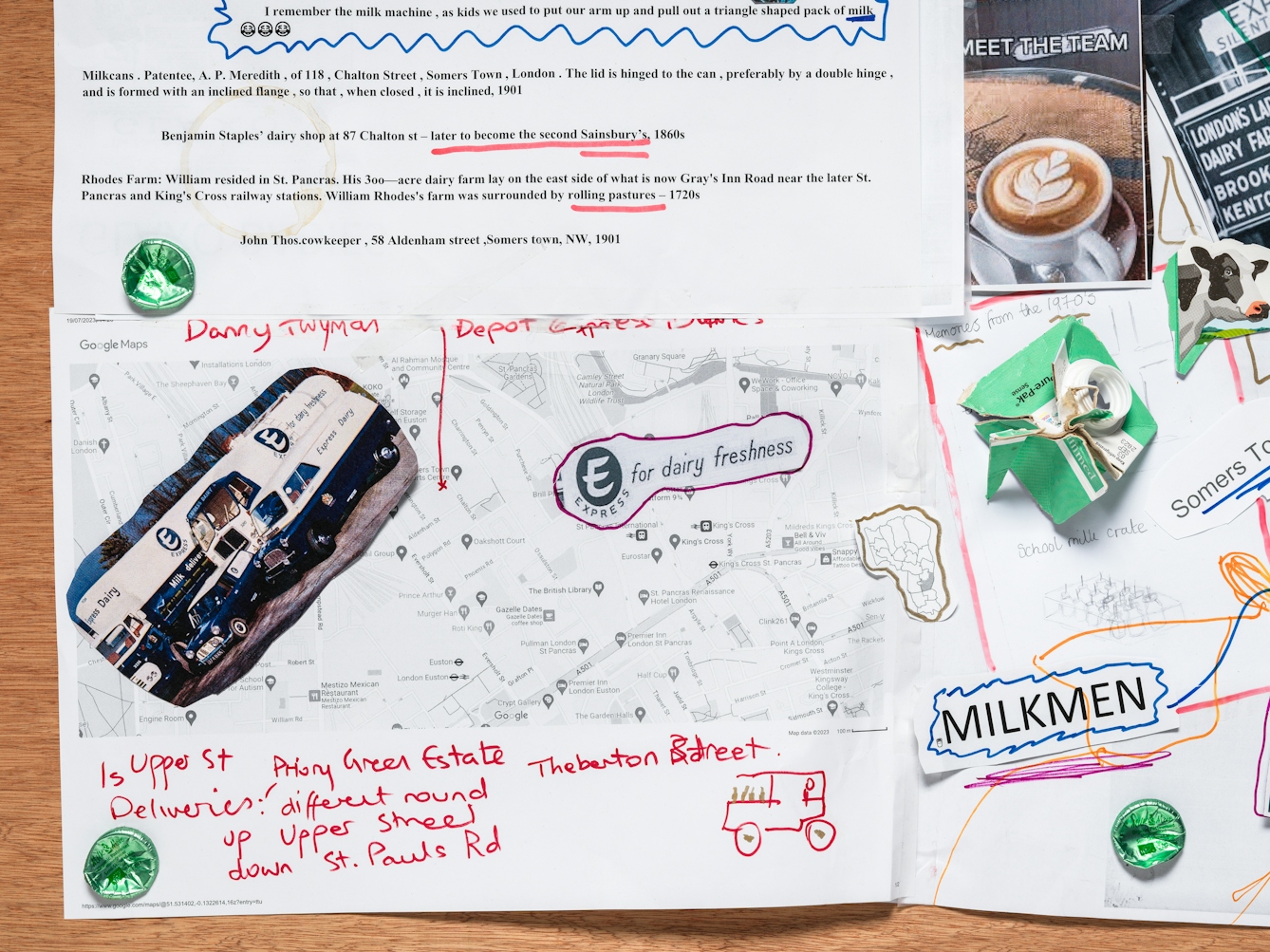

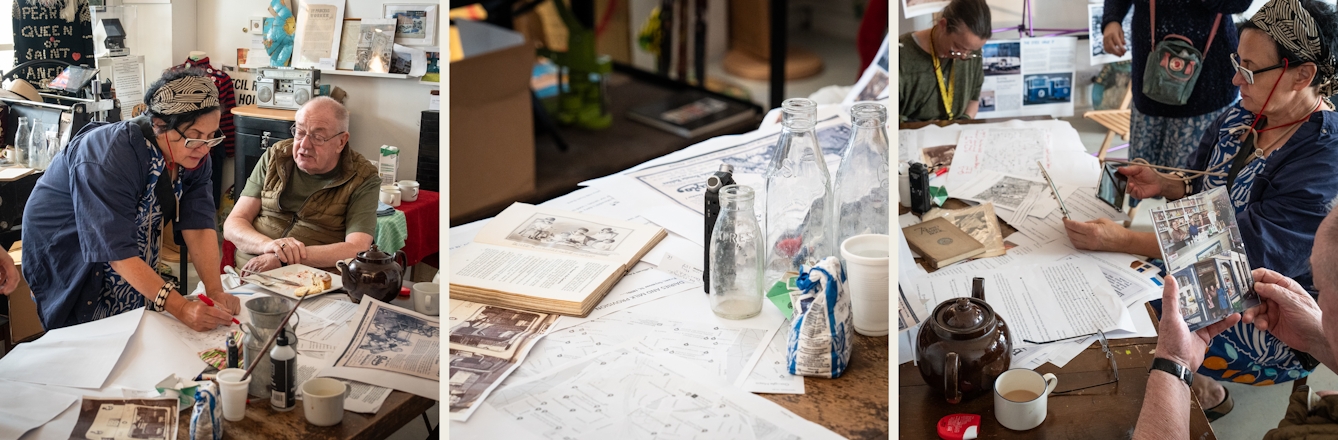

Collage artwork made in collaboration with Somers Town residents at the People's Museum, reflecting their experiences and stories of the local milk trade through the decades.

Supply chains in a growing industry

The urban dairies of London were hit by a cattle plague in the mid-1860s, which spread rapidly through the cramped cellars and filthy cowsheds. At the same time, building development in London meant that land available for grazing was disappearing. The railways were now beginning to deliver more and more country milk into the centre of the city from further distances.

The route from the West Country into London was the milkiest, but significant amounts arrived at Euston or St Pancras from Derbyshire and Leicestershire. Cows were milked in the country between four and six in the evening and the milk arrived in London at three or four in the morning, and met by a contractor who distributed further. One who used express trains took its mode into its name: Express Dairies.

Milk provision developed supply chains. The latest in US milk technology came too – the galvanised-metal milk churn. A photograph of the two-storey milk depot in Somers Town, where the Francis Crick Institute stands today, from around 1890, shows waistcoated porters unloading gleaming churns.

Refrigeration and chemical preservatives made the country milk more palatable. New systems pushed milk towards hygiene, coolness, standardisation and mingled unknown sources. By 1910, only two per cent of milk was produced in urban dairies. Milk flowed in on milk trains doing milk runs, until road haulage took over.

The milk that rushed in from the east of the country was distributed to dairy shops. At 87 Chalton Street, the owner grew a successful business in the 1860s into a small chain. His daughter, Mary-Ann, born in Somers Town, worked in one and met her love, John James Sainsbury. The two set up a store selling dairy and eggs in Drury Lane, where she served out the butter and insisted on hygienic practices. Her father’s original dairy shop, on the corner of Churchway, became another branch in the concern in 1882 – and by 1922, the firm was the largest grocery chain in Britain.

Annotated map showing the milk round George Sharp helped with as a boy in the 1950s. The milkman used a horse and cart and George remembers the horse knew the route so well, it would lead itself around, while George dashed up and down the buildings delivering milk.

A dose of the white stuff

While humans drinking the milk of another species was facilitated by the railways in the area, voluntary organisations turned their attention to the provision of milk for young children, as the stock of the nation was deemed unfit to enlist for the imperialist wars to be fought. The Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902, fought in Southern Africa, was not an easy victory for British imperialism, and the poor state of physical health among soldiers was pinpointed as one cause of military shortcomings. The majority of working-class males were not even fit enough to be recruited.

The Committee on Physical Deterioration was set up in 1903, and it recommended the teaching of mothering skills, school medical inspections and free school meals for the poor. In impoverished Somers Town, there was a 15 per cent infant mortality rate in 1904, and those who survived were weedy.

By 1910, only two per cent of milk was produced in urban dairies. Milk flowed in on milk trains doing milk runs.

A medical officer, in an effort to improve health, coined the term ‘mothercraft’ as a name for breastfeeding for extended periods. To encourage the practice, and to discourage what was called ‘hand-feeding’ (feeding babies an unwholesome semi-liquid mixture of bread, water and cereals), the St Pancras Mothers’ and Infants’ Society – known locally as Mothers’ and Babies’ Welcome – was opened in 1907 in the West London Mission Hall at the Euston Road end of Chalton Street.

It was the first of its kind in the country, with medical advice and a subsidised, cheap – one penny – wholesome meal for pregnant women and nursing mothers. Breastfeeding mothers could get free food for nine months. Fathers were invited in as well – and they might hear lectures on sleep, duties to an unborn child, working mothers and milk.

Danny Twyman was a milkman in the area for many years and remembers the Express Dairies Depot on Chalton Street. In 1983 he had his photograph taken for a Co-op calendar, standing beside his milk float.

They were unlikely to learn of what had occurred in the spot some 100 years before, when the writer Mary Wollstonecraft, dying in the Polygon off Chalton St after giving birth to her daughter, the future Mary Shelley, was compelled to suckle puppies. This was perhaps to draw off the milk that she could not feed, in her ill state, to her baby, or perhaps as a hoped-for cure for her puerperal fever.

The appeal of heritage

What remains of these trails of milk history? Some memories: for example, some recall from the 1930s an automated cow in front of Meredith’s, Milk Contractor at 119 Chalton St, purveyor of churns and other dairy equipment. At any time of day or night, it would dispense a pennyworth of milk. And, more tangibly, the stuff that surfaces from demolition sites: milk bottles, market tokens, a churn, fragments of tile, the trough.

Some of it is given a new home in the People’s Museum on Phoenix Road. A former local milkman visited recently – recollection of his delivery routes triggered a chain of memories of people and place.

Milk is still supped in the streets around here, but, squeezed between two railway terminals, the greater part of it may well be frothy lattes and flat whites, from the countless coffee bars, chains and otherwise. Dairy has become a selling point in the heritage-branded high-end housing sector – across the Euston Road, the Old Dairy is a name for a new mews development, a pastoral retreat from the “vibrant energy of King’s Cross and St Pancras”.

About the artwork

The collage artwork for this story was created during a community workshop run by Esther Leslie and Diane Foster at the People’s Museum, Somers Town. Local residents Danny, George, Alan, Ron and Cathy all recounted their memories of the milk trade in the area. The stories and experiences which emerged were brought together and represented through a collage- and mark-making collaboration.

Collage and mark making workshop at the People's Museum, Somers Town, London.

About the contributors

Esther Leslie

Esther Leslie is Professor of Political Aesthetics at Birkbeck, University of London. Her research includes European modernism and the avant garde, Marxism, science, technology and material culture.

People’s Museum

The People’s Museum: A Space for Us, is a community museum in Somers Town, London. It has been set up by local residents with the aim of playing a part in the sustainable development of cities and civic society, and reducing inequality. The museum creates a space to preserve local voices, to celebrate the histories of residents, to record the changes happening now, and to preserve local working-class heritage.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.