A 19th-century campaigner who condemned the practice of keeping a dead person at home before the funeral started a gradual trend for outsourcing the preparation and storage of a body. But as a consequence, one of the ways we process grief has been lost, explains historian Claire Cock-Starkey.

When terrible winter storms lashed the East Coast of America in December 2022, many people were cut off from medical help. As a result, a local nurse in Buffalo issued a set of instructions on social media on how to deal with a dead body. Her extremely sensitive post included the key information that “a dead body is not an emergency and is safe to have in the home for a few days” and ended with the poignant, “It is OK to touch your loved one, to hold their hand or kiss their cheek.”

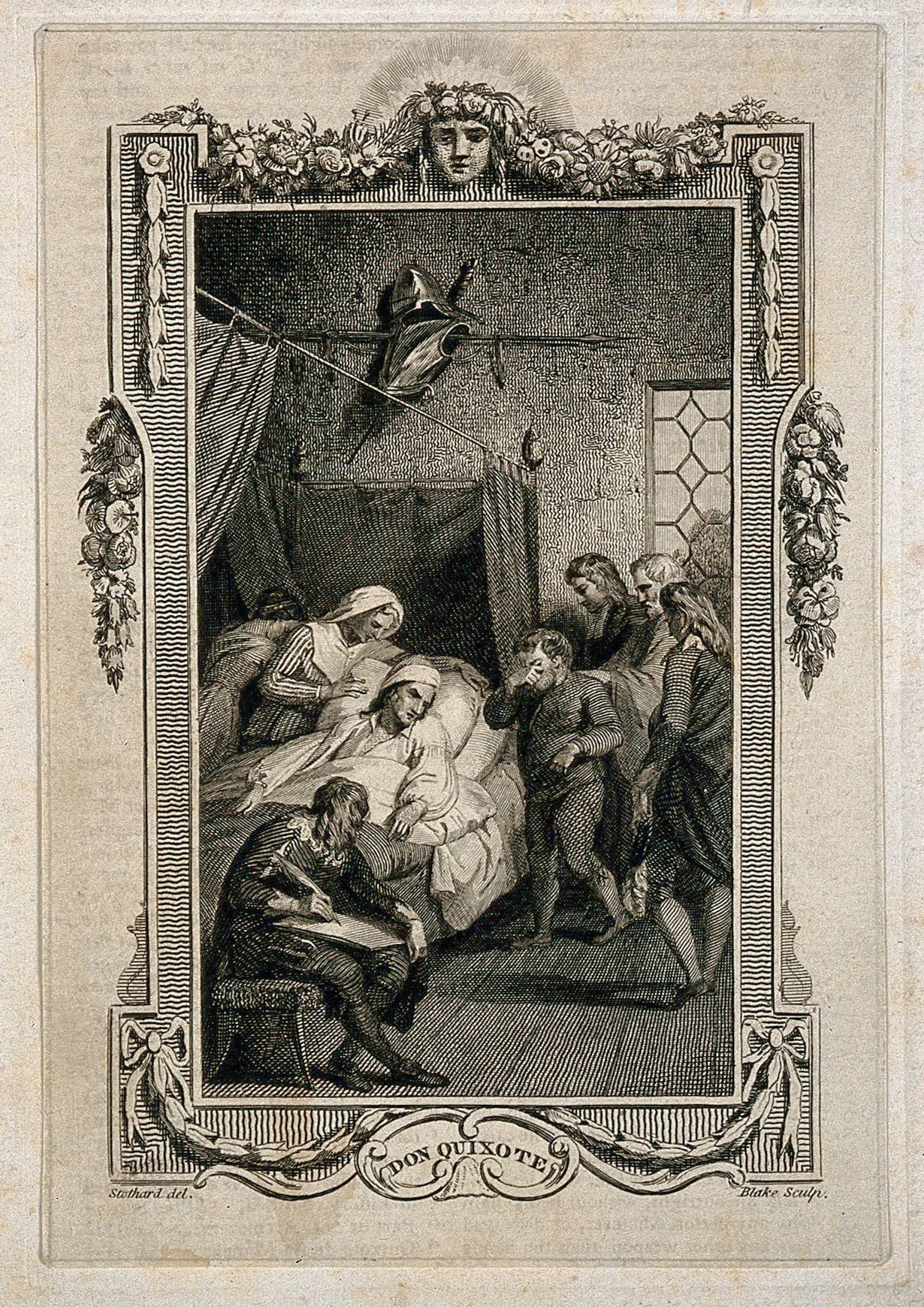

Most people now die in hospital, care homes or hospices, tended by medical professionals, which means that we have become divorced from looking at the dead. After a death has occurred, undertakers whisk the body out of sight and prepare it for burial. Furthermore, very few people now choose to have an open casket, meaning that most of us have never seen, or touched, a dead body.

This might seem like a positive development, but this distance from the reality of death can make accepting it more difficult and can form a barrier to effective mourning. It wasn’t always this way.

The time between death and burial

Up until the mid-19th century it was customary across all classes in England to keep the dead body of a loved one in the home in the period between death and burial, which could be anything from between two and ten days. But in 1843 a sanitary-reform campaigner named Edwin Chadwick published a report on urban death practices in which he called critical attention to this traditional working-class custom and reframed it as a risk to public health.

“Distance from the reality of death can make accepting it more difficult and can form a barrier to effective mourning. It wasn’t always this way.”

Chadwick argued that dead bodies gave off ‘miasma’ – an unhealthy vapour – that he believed was harmful and urged that bodies be removed quickly from the home and managed by professionals.

The cramped living conditions experienced by the urban lower classes were not considered a suitable environment for a dead body, and Chadwick decried the situation, writing that bodies retained in the home represented “a distressing scene, and moreover a case of peculiar danger and probably permanent injury to the survivors amongst whom it takes place”.

Chadwick’s report has come under valid criticism from modern scholars for his failure to speak to any actual working-class people and instead using evidence submitted by largely middle-class witnesses such as clergy, burial-club secretaries and doctors. This meant that the experiences of the working classes themselves were not reflected in the report and instead their emotional response to the corpse was imagined and disdained.

In cities, where overcrowding, and overflowing cemeteries, meant that burial reform became a pressing issue, Chadwick’s intervention proved to be influential. However, in rural areas, where the pace of change was slower and the pressures of urban living were not felt, the tradition of keeping the dead body in the home for a number of days before burial continued.

My research into rural working-class burial customs, which I have gathered from 19th-century collections of folklore and working-class autobiography, provides a different reading from Chadwick’s horrified response to the practice of keeping the body in the home. Actually, the family rituals of laying out the body, dressing it in grave clothes, visiting and touching the body in farewell, were infused with meaning.

“Chadwick argued that dead bodies gave off ‘miasma’ – an unhealthy vapour – that he believed was harmful.”

The appearance of the corpse took on great importance in the working-class home because many people would look at it in the days before burial. It was essential then that the body be prepared in the customary way.

Preparing and visiting the body

The first step of the process was to wash and lay out the body: the limbs would be straightened and tied together so the body would fit neatly in the coffin, the eyes were closed and the jaw tied shut, the hair combed and, for men, the chin shaved. The corpse was then dressed in grave clothes; the outfit selected, which was often the “Sunday best”, serving as an important marker of identity.

The purpose of carefully laying out the dead was not only an act of love and respect towards the dead themselves but it also acted as an aid to memory-making for the friends and family of the deceased.

Dead bodies decompose, they seep liquid and they smell bad. Laying out was a way of ensuring that, despite the odour of decay, a body looked peaceful and at rest. When friends and family took their final look at their loved one, they were not greeted with an uncanny gaping mouth or unseeing open eyes; instead, the careful presentation of the corpse offered a picture of quiet repose.

Once the body had been prepared and laid in its coffin it would remain on show, allowing for the customary visits from friends and family to make their final farewells. Visiting the corpse frequently took on a sensory element, as it was traditional for people to touch the dead body, its very coldness conveying the reality of death.

“The appearance of the corpse took on great importance in the working-class home because many people would look at it in the days before burial.”

In 1898, folklorist Richard Blakeborough described the emotional resonance of this moment: “It is looked upon as a kindly action, when standing by the corpse of some dear one, if the visitor gently touch the same. In some undefined way, this solemn contact of the living with the dead, makes known to the sorrowing ones that nothing but sympathy is felt.”

Although Chadwick might have railed against the potentially negative impact of keeping a decomposing body in the home, the practices recorded in 19th-century folklore collections reveal that these rituals in fact allowed rural working-class families to show their great respect for the dead. Having the corpse of their loved one in the home provided a focus for their grief and an opportunity to process their loss.

The professionalisation of undertakers and the medicalisation of death towards the end of the 19th century meant that it became increasingly rare for families to care for and prepare their own dead for burial. Today, we have become deskilled in dealing with the dead.

Perhaps, by looking back at the traditional practices of the rural working classes, we could appreciate the care and compassion shown by their personal contact with the dead and learn how these practical and ritual processes could help families come to terms with their loss.

About the author

Claire Cock-Starkey

Claire Cock-Starkey is a writer and part-time PhD student at Birkbeck, University of London. Her project examines the folklore of death and dying in 19th-century England. She is also co-convener of the death studies discussion group Grave Matters. Her latest book on folklore for children is ‘Lore of the Land’.