In the event of a nuclear attack on the UK, would the NHS cope or would it collapse? At the height of the Cold War, answering this question became increasingly urgent for the UK government and the medical community.

In 1958, an official government booklet, ‘The Hydrogen Bomb’, admitted that in the event of a nuclear attack on the UK, “there would be far more injured people than even the expanded hospital service could cope with”.

By the 1980s, the picture hadn’t changed much, and those in power had few answers. “Casualties could occur on a scale which would overwhelm surviving hospital resources in some areas, depending on the scale of attack,” admitted the Home Office’s confidential guidance to the police.

In public, though, officials put on a braver face. At a 1982 event held at the Royal College of Physicians, Dr Michael Prophet of the Department of Health and Social Security told delegates: “We cannot base our plans on the assumption that the very worst case will actually occur.”

Optimistically, he explained that doctors could lead the country into its shining, post-apocalyptic future: “There will be those who would want to rebuild and clear up the mess. Who better than doctors with their basic knowledge of preventive medicine to join in with those who wanted to rescue something from a holocaust?”

Grim predictions

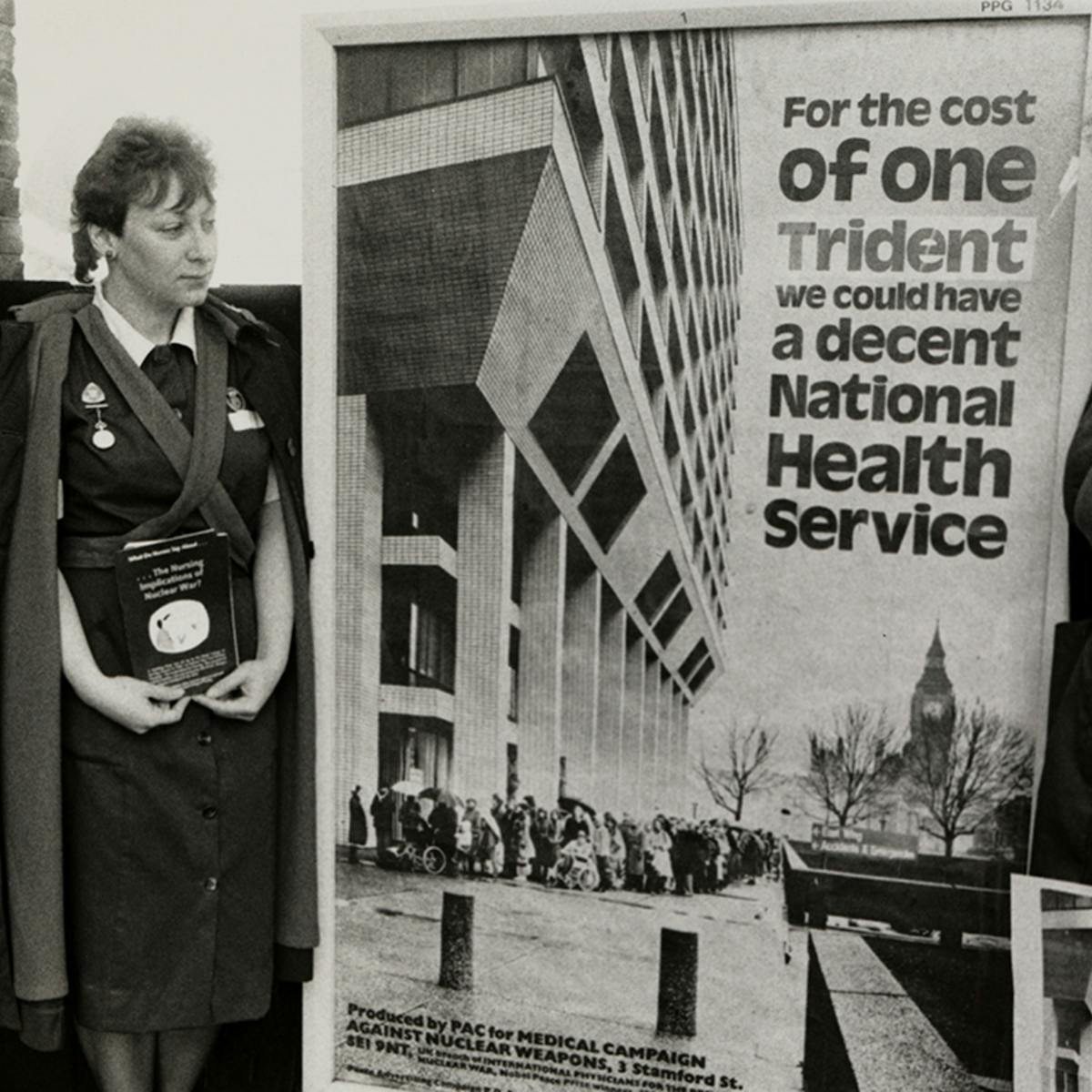

To members of the medical peace movement, the prospects seemed less bright. The Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (MCANW) – formed in 1980 by health professionals, including doctors, nurses and researchers – employed medical arguments to make the case against nuclear weapons and the concept of a ‘winnable’ nuclear war.

MCANW believed “there could be no effective medical response” to nuclear weapons. It predicted: “The management of casualties resulting from even a limited nuclear attack would be completely beyond the capacity of existing, fully operational medical facilities.”

In pictures

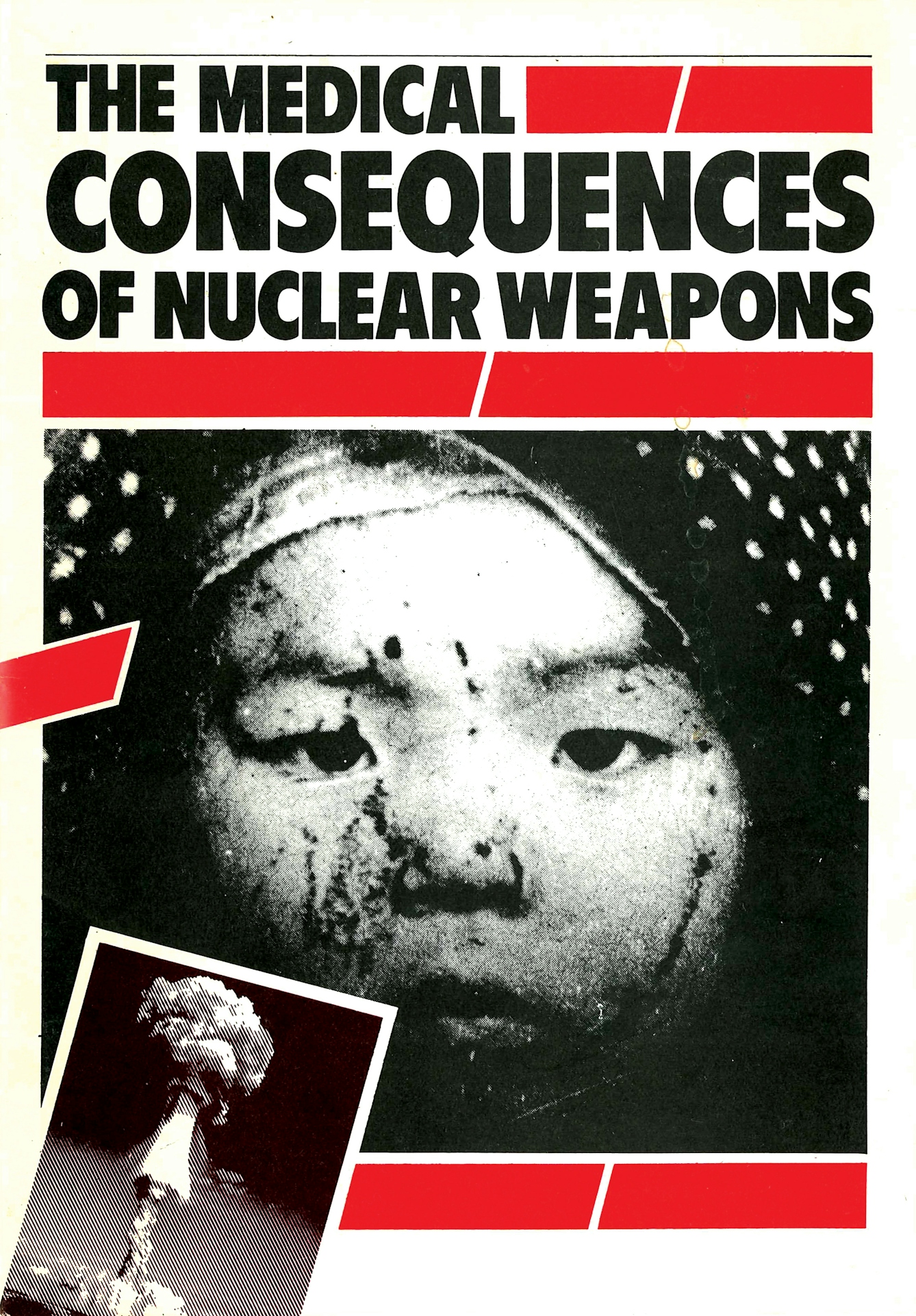

‘The Medical Consequences of Nuclear Weapons’ was produced by The Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (MCANW), which was formed in 1980 to highlight the medical implications of a nuclear attack and to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

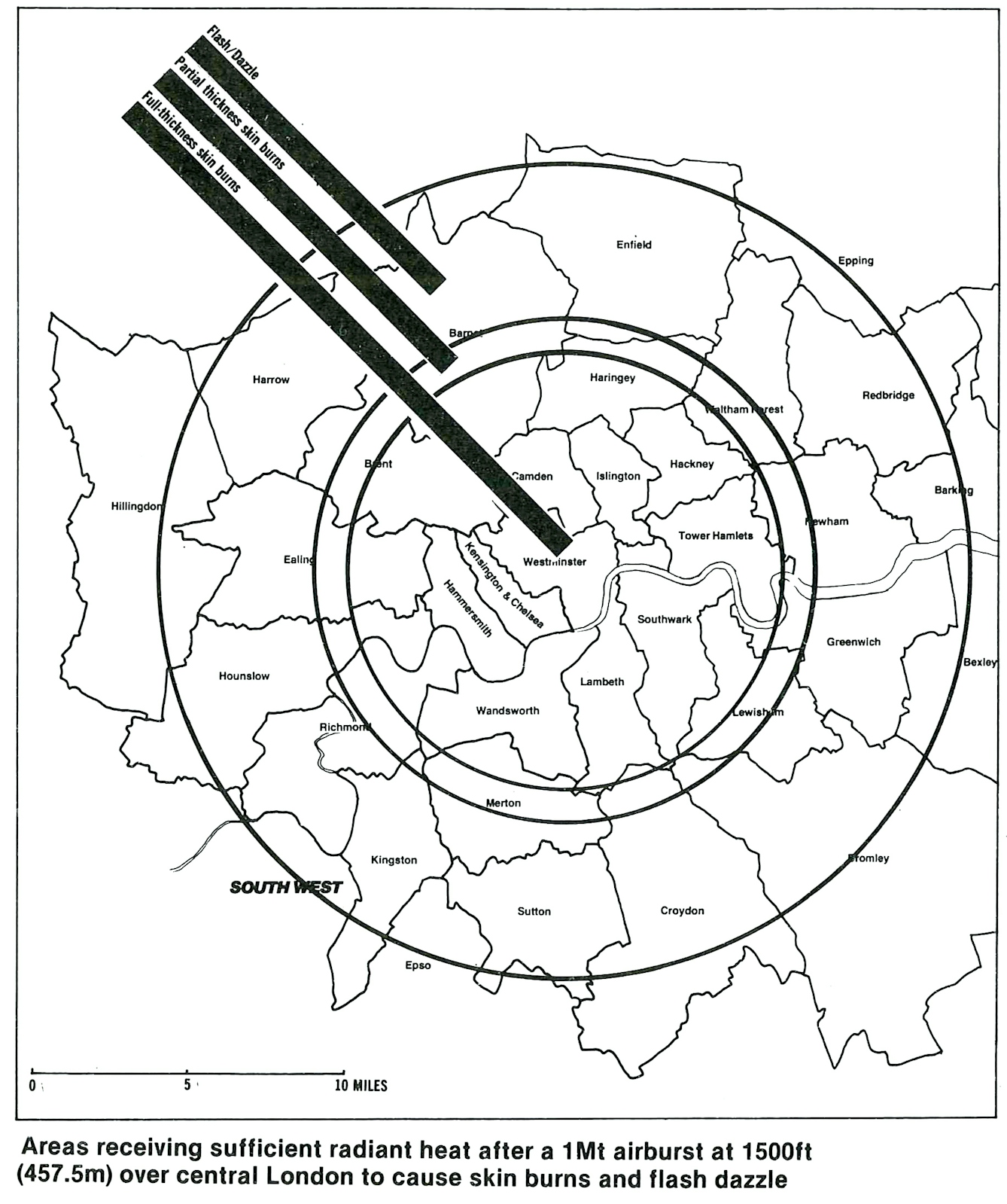

This map from ‘The Medical Consequences of Nuclear Weapons’ shows the likely effects of a nuclear blast and the predicted casualties.

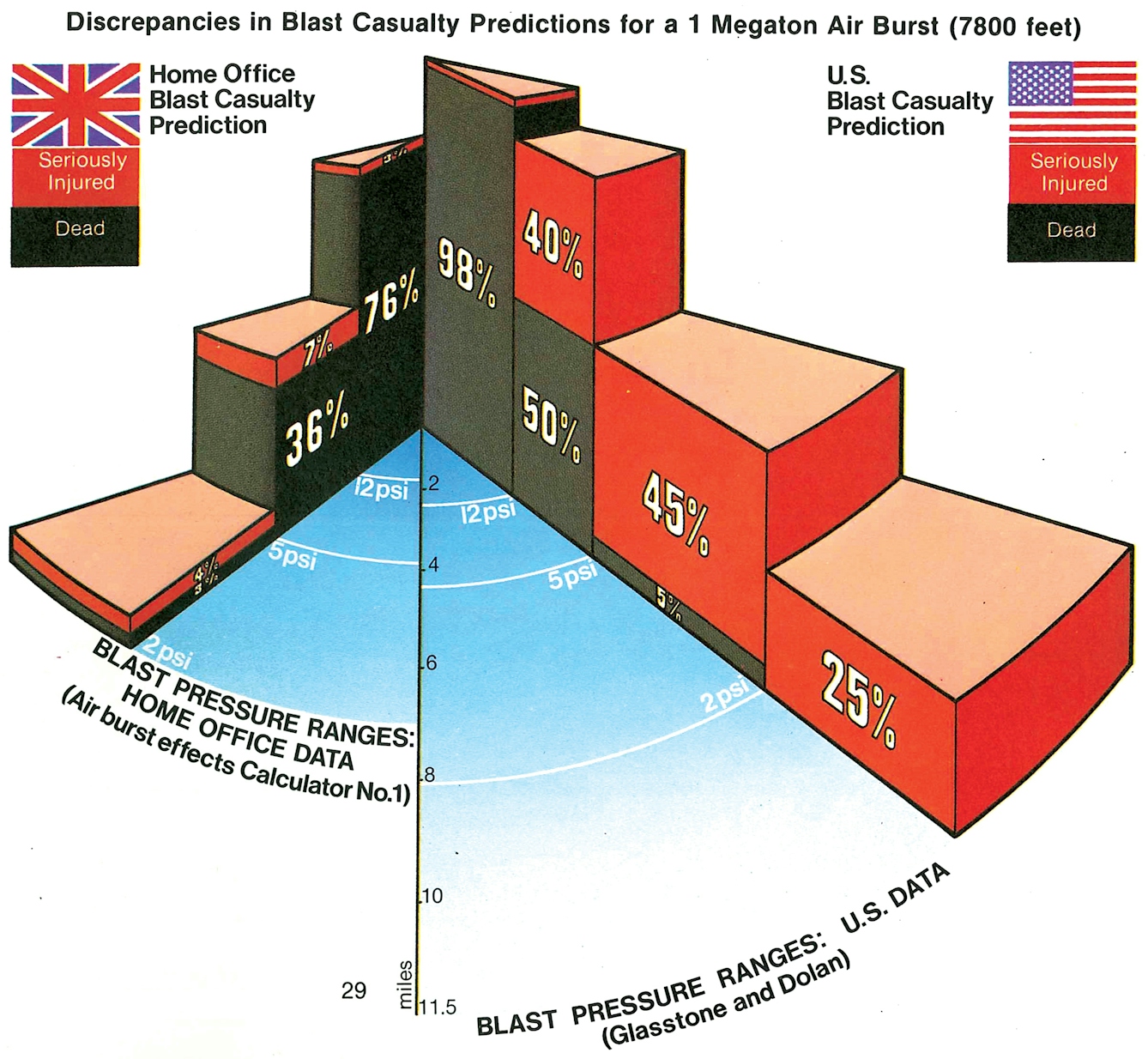

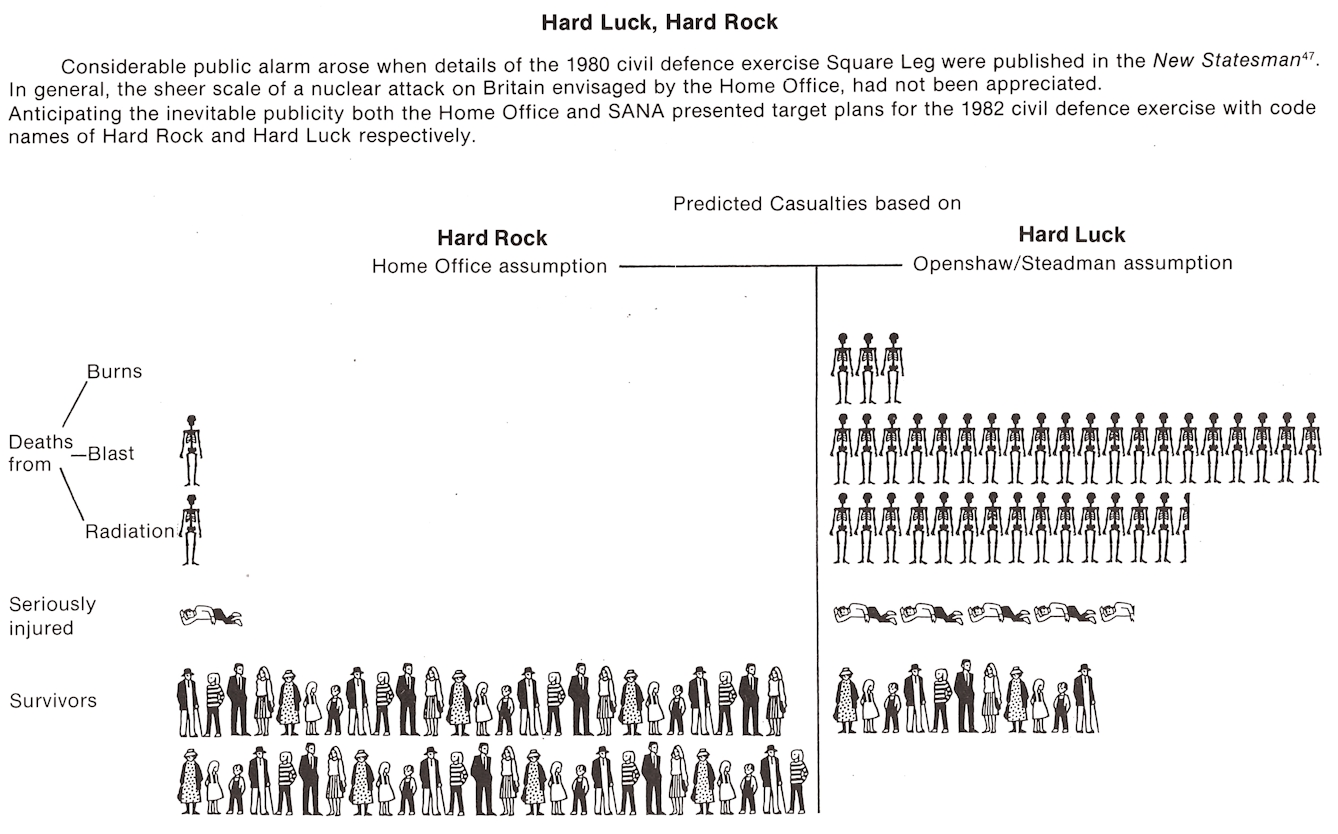

MCANW also produced ‘The Nuclear Casebook: an illustrated guide’, which analysed discrepancies in official predictions of burns casualties.

Official predictions of nuclear casualties in the early 1980s were later understood to be serious underestimates.

Professional associations representing ordinary doctors and nurses conducted their own assessments on behalf of their members, too. Based on a realistic understanding of how well prepared the medical community was, these reports are arguably the most impartial, and the most revealing.

A panel from the British Medical Association (BMA) conducted a comprehensive, 18-month study – “an objective and scientific account” – of the medical implications of a nuclear attack. The results were made public in early 1983, and they made for grim reading.

Millions at risk

The BMA found the Home Office’s predicted casualty figures were significantly more conservative than most other estimates (including those of the US Office of Technology Assessment). The BMA estimated, for example, that there would be 2 to 3 million deaths from those burnt by exposure to an atomic blast; the Home Office chose not to take this factor into account, despite other government departments warning of vast numbers of burn casualties.

Government estimates suggested that fewer than a million deaths would result from fallout, while others estimated as many as 11 million. The BMA erred on the higher side, as Britain’s dense population meant strategic Soviet targets, such as military bases, were frequently found close to population centres.

A character from Raymond Briggs's ‘When the Wind Blows’ reacts to the BMA report. Briggs' famous graphic novel depicts an elderly couple trying to survive a nuclear attack.

The BMA believed that the yield of enemy weapons that would strike the UK could be three to four times the government’s assumptions.

Yet just one Hiroshima-sized bomb dropped over any UK city would “completely overwhelm” the UK’s medical services, due to trauma and burns alone – not even taking fallout and radiation sickness into account. “It follows,” the study’s authors wrote, “that multiple nuclear explosions over several, possibly many, cities would force a breakdown in medical services across the country as a whole.”

Even seemingly positive actions could have catastrophic health implications: survivors were likely to adopt a ‘Blitz spirit’ and cluster together, facilitating the spread of disease to their radiation-weakened immune systems. There would be little that doctors could do.

The panel’s conclusion was stark: Britain’s medical community could only be prepared for nuclear catastrophe by being on a permanent war footing. Otherwise, even the smallest Soviet attack “would cause the medical services in the country to collapse”.

Propaganda or realism?

MCANW suggested that action to prevent a nuclear war was more valuable than preparedness.

The BMA’s report caused concern within the UK government. In an attempt to head off its impact, the Home Office wrote to scientific advisers across England and Wales, claiming the report was “strongly influenced by CND-type propaganda”, and that it could not be regarded as an objective scientific document.

The Daily Mail attacked the “BMA horror report” as spreading “quack Kremlinology”. However, this view was not shared within much of the medical community. World Medicine magazine called the report “uncharacteristically brave” and “meticulously non-political”, but did point out that the report’s publication itself – with its conclusion that the NHS could not survive a nuclear attack – meant the BMA had essentially taken a political position.

The nurses’ union, the Royal College of Nursing, wrote its own 1983 report on nuclear war, calling the government’s plans “totally inadequate”, “naïve” and “misleading”.

In the RCN’s view, a post-apocalyptic society wouldn’t see a return to medieval conditions, but something even worse as, unlike in medieval times, there would be virtually no access to safe food, clean water and adequate shelter.

The government’s argument that the worst case was only one of a range of possible scenarios was undermined by the fact that even the smallest nuclear attack would cripple the NHS. The RCN concluded with a chilling statement that echoed the BMA’s findings: “All the adjectives of doom in the English language would hardly do justice to the effects of a nuclear strike involving one major weapon.”

About the author

Taras Young

Taras Young is a researcher and writer interested in weird, hidden and forgotten ideas. He is the author of Apocalypse Ready, a new illustrated history of 20th century public information on pandemics, natural disasters, nuclear war and alien invasion.