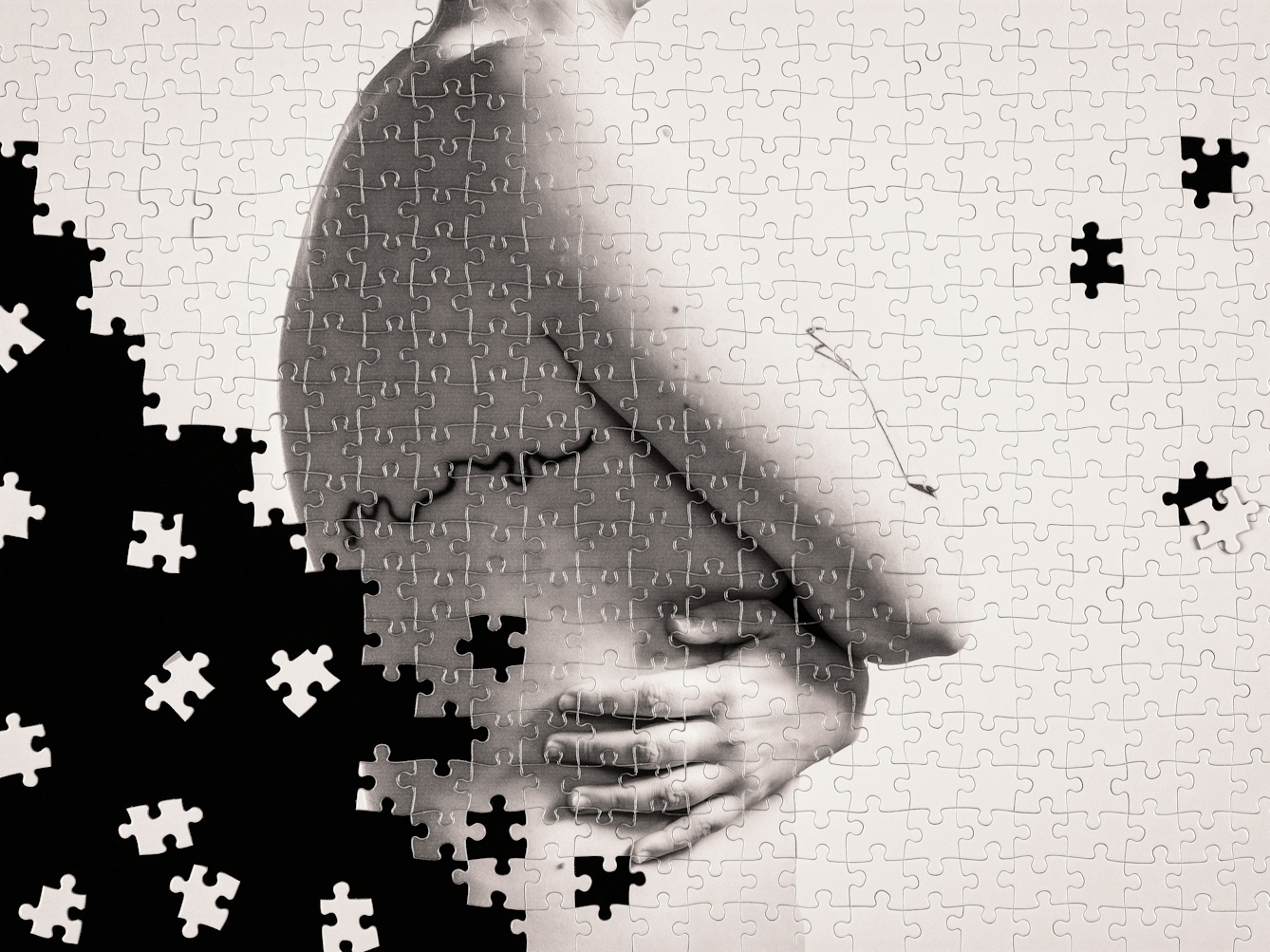

When Jessica Furseth found out she’d inherited a gene that means she might get cancer, it was like a bomb went off. For years afterwards, she felt fractured, dissociating from her body and its potentially faulty parts. In this essay Jessica asks, after the shock of diagnosis, how do we learn to put ourselves back together again?

I was standing on the terrace of my London flat when I got the phone call from my genetics counsellor. “I’m sorry to tell you that you’ve inherited your family’s genetic abnormality,” she told me.

I’d been in her office a month earlier, nodding along as she explained how the cancer cluster in my family was down to a gene that left carriers more susceptible to certain types of cancer. I had a coin-toss of a chance of having it too, she said, sending me off to get the blood test that would let me know for sure.

I was brazen – I simply didn’t think I’d have it. So when she told me otherwise, it was a shock. I got off the phone as quickly as I could. It was like a bomb had gone off. I wasn’t sick, and I might never be sick, but all of a sudden my body felt like an impostor and my trust in it was eviscerated.

When there’s an explosion on film, people drop to the ground and curl up, braced. It’s not a bad metaphor for how I spent the next few years. I was young and unlikely to get cancer right away, and I might never get it. But that’s not how doctors talk to you – for them it’s all about risk and illness and death.

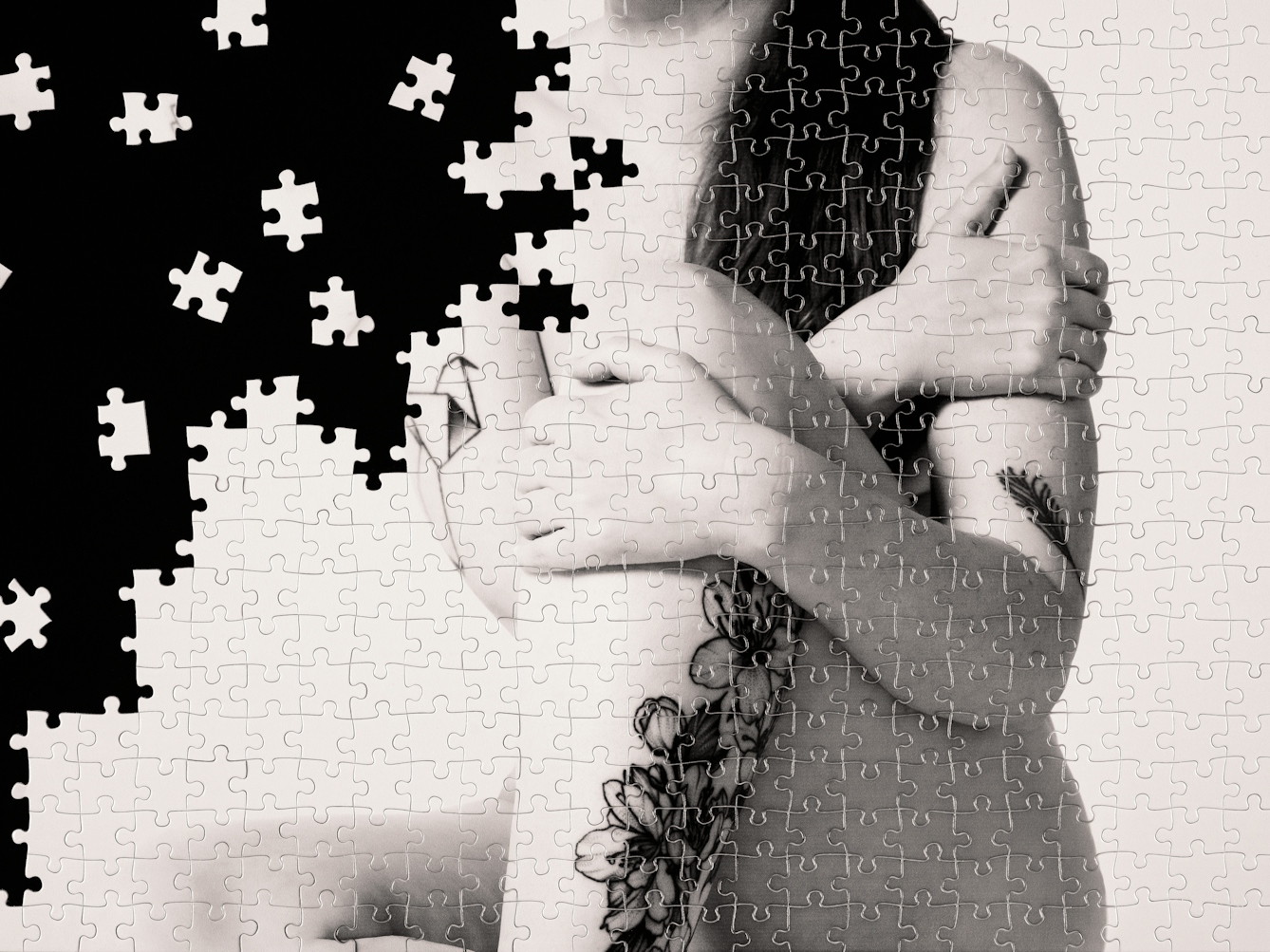

I hated the way they only cared about single parts of me. I met with specialists who examined just my intestines, and then with others who didn’t care one bit about my bowels but spent hours talking about my uterus and how maybe one day it would need to go, and would I like to start thinking about that?

“It was like a bomb had gone off. I wasn’t sick, and I might never be sick, but all of a sudden my body felt like an impostor and my trust in it was eviscerated.”

I hated the preventative screenings even more. They are brutally invasive, forcing scopes into parts of your body that were never meant to be looked at. No matter how many drugs I’m given, there’s always a moment when the pain sears through me, reminding me of how vulnerable my body is now, and that the best outcome is to keep having these scans for ever. Yes, I’ve thought about quitting.

Knowing that you have a high chance of becoming sick is a double-edged sword. All those distressing scans are my choice, and I do them so that if something happens, I will know about it in good time and can take action. This is covered in the brochures, but what they don’t tell you is how you’re becoming a patient through all this, maybe for nothing.

It was my decision to do the genetic testing and the screenings that followed, but it never felt like much of a choice – doing nothing wasn’t a neutral state, because now I know.

Into the woods

I didn’t quit the screenings – cancer is too scary a prospect. But in the years that followed I quit a lot of other things. I didn’t go to the dentist, I didn’t go to the optician, I didn’t get a smear test, and I even avoided the hairdresser – I steered clear of all of the places catering to parts.

I attended my hospital appointments as I squinted through my old glasses and my hair grew long down my back, and afterwards I sat outside and smoked a cigarette – I don’t normally smoke, but it was something I could control.

“I didn’t quit the screenings… But in the years that followed I quit a lot of other things. I didn’t go to the dentist, I didn’t go to the optician… I steered clear of all of the places catering to parts.”

I needed… to simply feel angry and low-key self-destructive for a while.

For the same reason, I worked in bed and not at my desk. When my back started aching, the pain drove me to see an osteopath, where I lay face down and tried to deflect her questions as politely as I could while she dug into my back with her elbows and hands.

I went there to sort my back out, but osteopathy takes a whole-body approach – it seemed that while I didn’t want to talk about it, my body did. I would giggle and cry as my back let go of tension – the osteopath said this happens all the time.

I didn’t want to talk about my dud gene with my therapist either, who I’d started seeing for unrelated reasons. I spent months with him before I mentioned my diagnosis. His eyes widened as he flicked to a fresh page in his notes.

After I’d explained the practicalities to him, I found myself not really having anything more to say. I might get cancer. I was born like this. Nothing has changed. Knowing about it means I can protect myself. But I also feel betrayed. I am angry and sad.

“I went there to sort my back out, but osteopathy takes a whole-body approach – it seemed that while I didn’t want to talk about it, my body did.”

I shrugged at my therapist and he looked at me with a kind, open expression that seemed to say: What you are feeling is okay. I know now that what I needed was space – to simply feel angry and low-key self-destructive for a while.

In the end, it was my bad back that did it. After the osteopath got me walking upright again, we went into lockdown, and its toxic mixture of anxiety and boredom forced me to look at the one thing I’d been avoiding: my body.

Trusting my body again

It’s not very original to say that I discovered exercise during lockdown, but it came as a complete surprise to me. I was honestly a little scared as I rolled out my old yoga mat. I’d made such a fuss about wanting to be treated like a whole person for all these years, but in all that time, I hadn’t actually fully inhabited my body.

Moving properly after so long felt like plunging into a freezing-cold lake after a winter spent under thick layers. Drenched with sweat, I mindlessly followed the teacher’s instructions and kicked my feet up against the wall, stunned to find myself standing on my head for the first time in my life.

A memory flashed me back to my first monkey-bar flip as a kid, when I spun around the bar before I had time to worry about falling – back when I trusted my body to just do what I asked of it.

“It’s not very original to say that I discovered exercise during lockdown... I’d made such a fuss about wanting to be treated like a whole person for all these years, but in all that time, I hadn’t actually fully inhabited my body.”

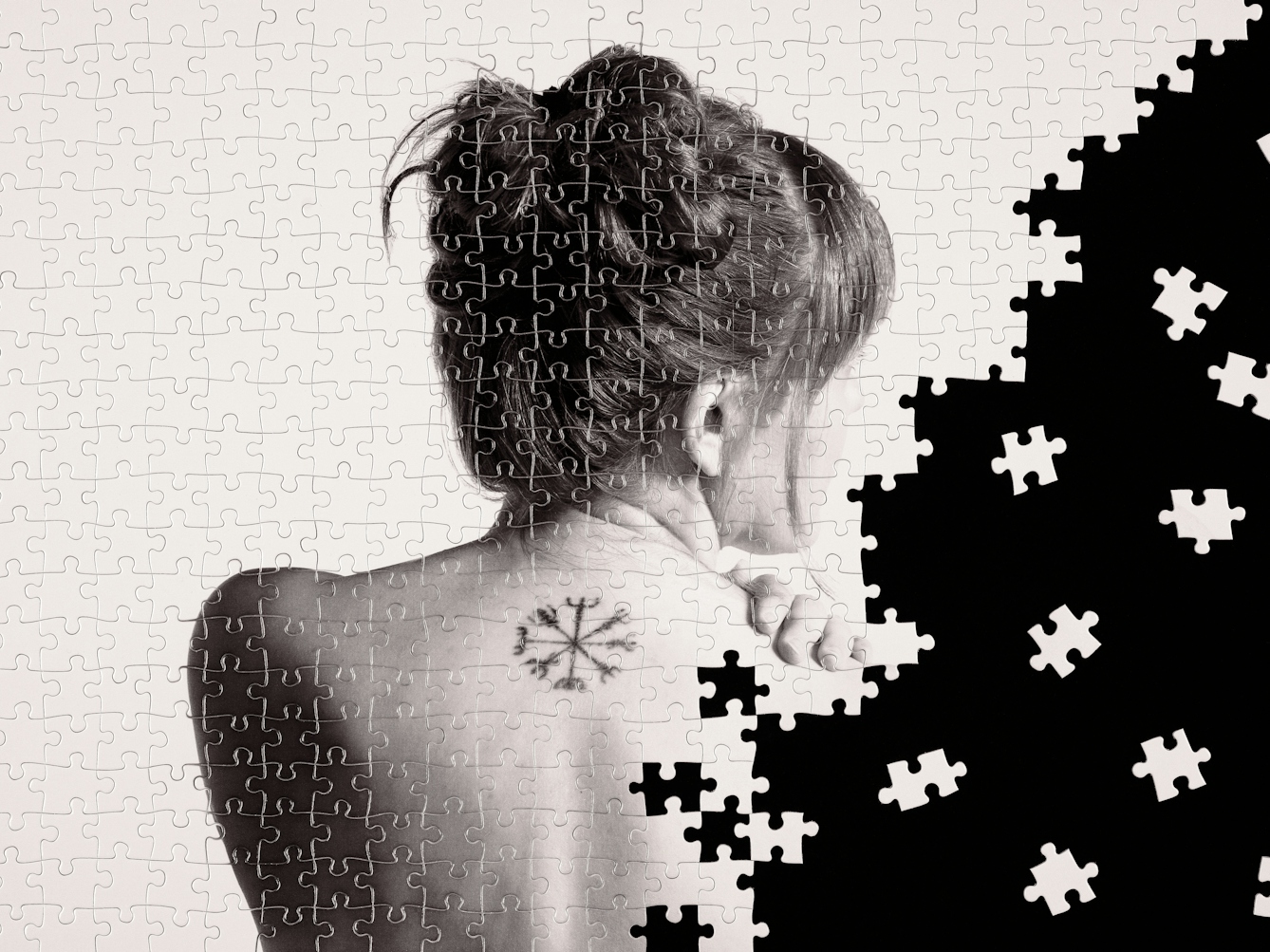

I collapsed back onto the yoga mat, blood pumping into my toes and fingertips. I’d disassociated from my body for so long that I didn’t even realise I was doing it any more. Now I could feel myself present in it, creaky and vulnerable but wide open.

I got a haircut after the first lockdown ended, my smear was fine, my new glasses have been ordered and I’m seeing the dentist next month. I had another routine check-for-cancer scan, where I opened my eyes during the procedure to watch my insides unfold on a screen, soft pink and healthy.

I know I was on a lot of drugs, but as my insides were twitching, I think they might have been winking at me. Those parts of me I’d been repeatedly told were moments from breaking down were still going strong, doing exactly what they’d always done, taking care of me.

I won’t ever be the same as I was before I knew about my rogue gene, but my body and I are friends again. Now I do yoga three times a week whether I want to or not, because I need to stretch out into the far reaches of my body to keep myself there – and if I don’t, my back forces the issue.

I might still get cancer and will never be graceful about that, but that’s okay. Time has done its thing. I know now that my body is here for me, and I can still trust it, even after everything.

About the contributors

Jessica Furseth

Jessica Furseth is a journalist living in London. She writes about culture and urbanism, how technology is changing the way we live, and agency around health. You can keep up with her work via her infrequent newsletter.

Kathleen Arundell

Kathleen is a freelance photographer working in the culture and heritage sector. She works in a range of museums across London, and loves all things science and art.