Throughout history, gay men have had to confront the fact that their affections and behaviour could see them ostracised, jailed or even executed, depending on the social norms of the world they happened to find themselves in. Ben Gazur samples their complex history in London during the last 600 years.

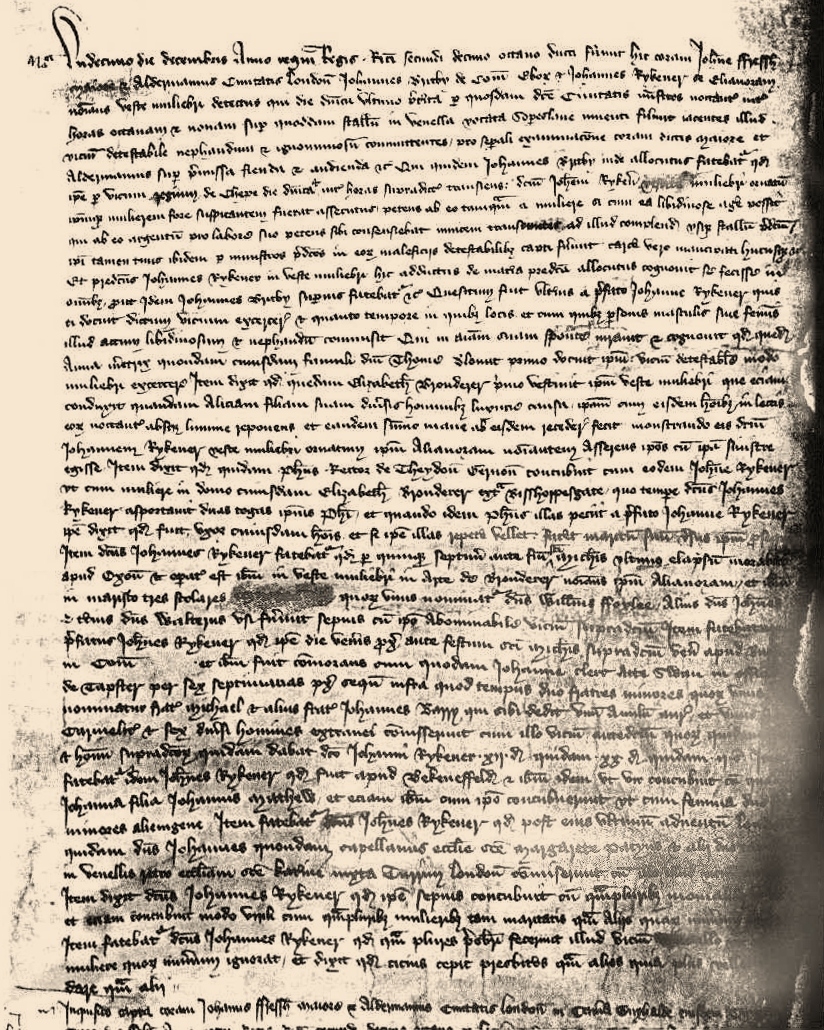

LGBTQ history can be difficult because our modern concepts of gender and sexuality may not have been recognised by people in the past. In 1394 John Rykener was caught “lying by a certain stall in Soper’s Lane [in what is now the City of London] committing that detestable, unmentionable and ignominious vice”. Rykener was a male sex worker who sold his body to other men. But court records tell us that Rykener dressed as a woman and went by the name Eleanor, raising the question of whether Rykener was a gay man or a transgender woman.

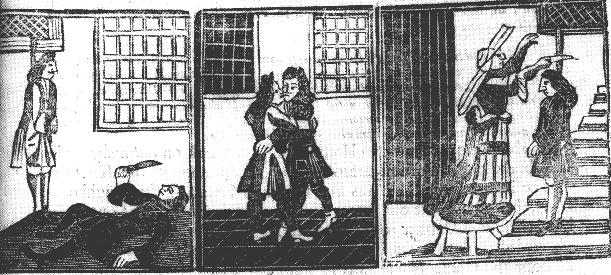

Homosexual acts were made punishable by death in the Buggery Act of 1533. Yet men continued to have sex with men. In 1707 40 gay men were captured at a club near the Stock Exchange. Broadsides such as The Woman-Hater’s Lamentation made clear the fates of these “sodomites” when it showed them either hanging themselves or slitting their own throats.

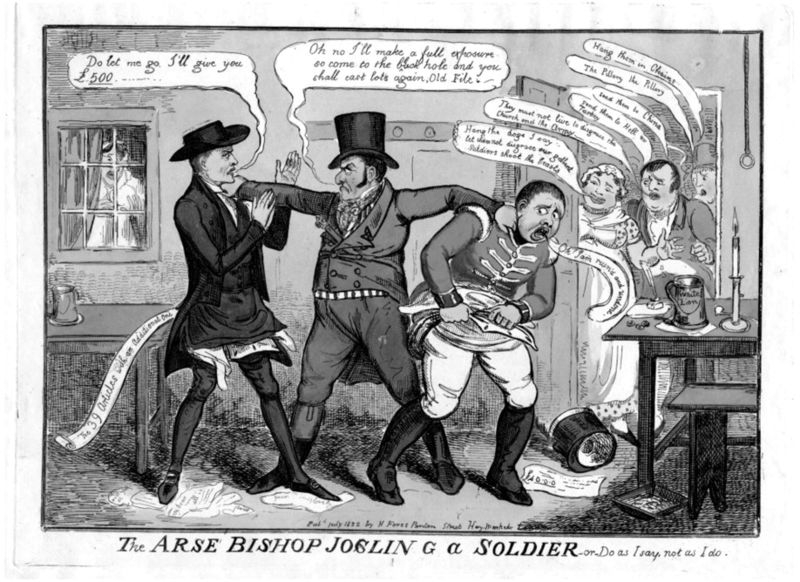

Despite the dangers of discovery, gay men continued to gather. Some visited molly houses, where they could openly show affection. Others preferred more private meetings. In 1822 Percy Jocelyn, Bishop of Clogher, was caught in the White Lion pub with a Grenadier Guard, both literally with their trousers down. After being granted bail, the bishop fled. The Archbishop of Canterbury declared “it was not safe for a bishop to show himself in the streets of London”, such was the public outcry.

While the death penalty could be, and was, handed down for buggery, there were limits on its imposition. An alternative punishment was the notionally more lenient pillorying. Being placed in the pillory, though, opened a homosexual to the most brutal public treatment. Charles Hitchen was subjected to the pillory for sodomy in 1727 and his friends attempted to hold back onlookers with coaches and carts. A mob of female prostitutes broke through. They pelted him with rocks and filth so harshly that Hitchen never fully recovered, died seven months later.

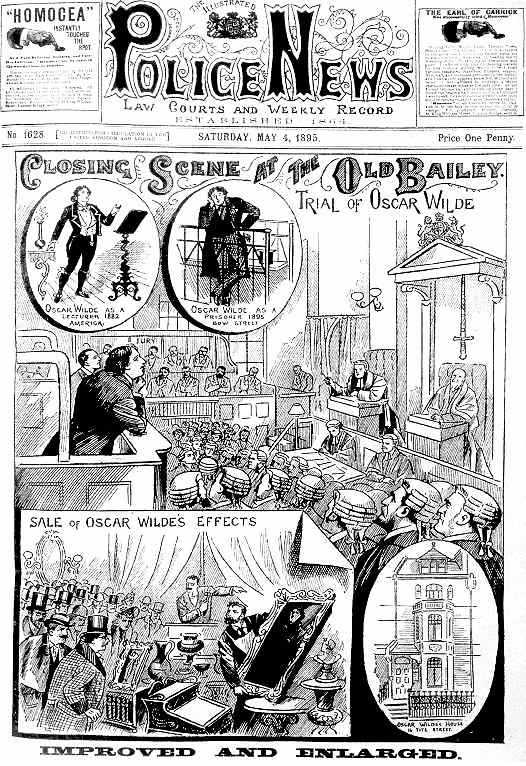

The homosexual panics of the 18th century slowly faded. No gay men were executed for sodomy after two men were hanged in front of Newgate Prison in 1835. In the 19th century it was common for male friends to walk arm in arm and be seen doing so in fashionable Hyde Park. That changed after the conviction of Oscar Wilde in 1895 for “gross indecency” and the public shaming of other homosexuals. Being known as gay was social suicide on the London scene.

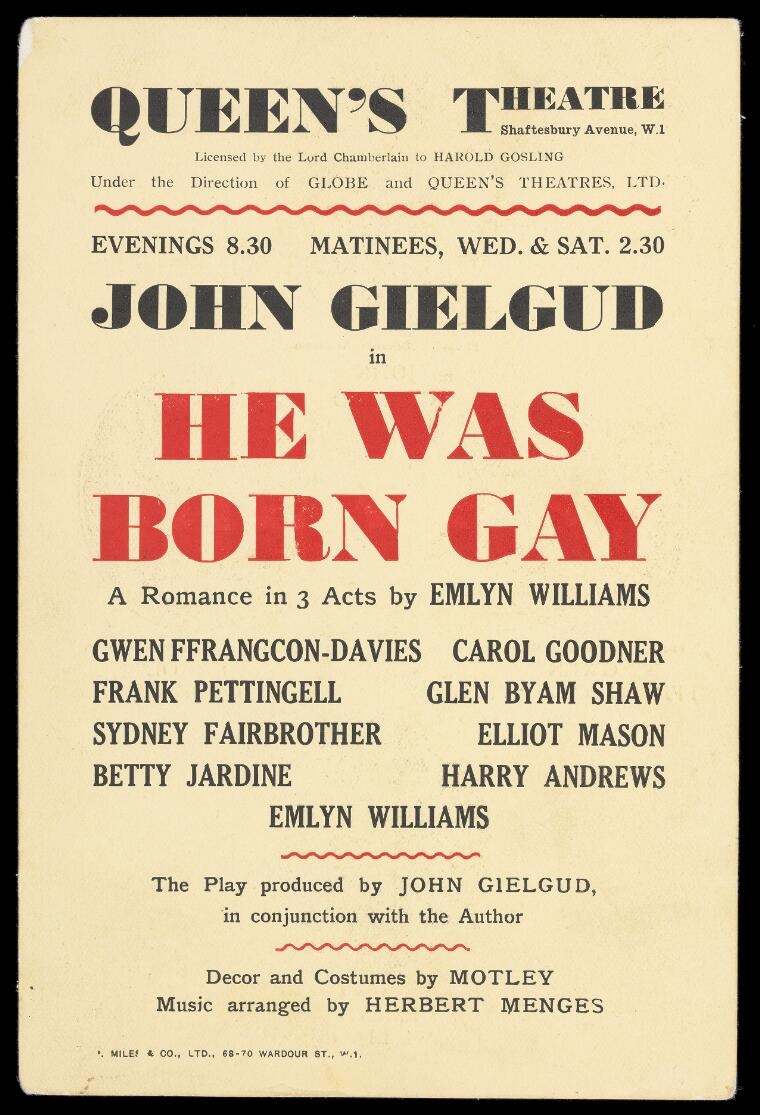

Homosexuality remained illegal in England and Wales until 1967, but public opinion had begun to change in the 1950s. Actor John Gielgud was arrested for ‘cottaging’ – or “importuning for immoral purposes” – in a Chelsea toilet. He feared his career was over. When he returned to the stage, though, he was welcomed with applause by the audience. Fellow actor Dame Sybil Thorndike merely commented, “Oh John, you have been a silly bugger!”

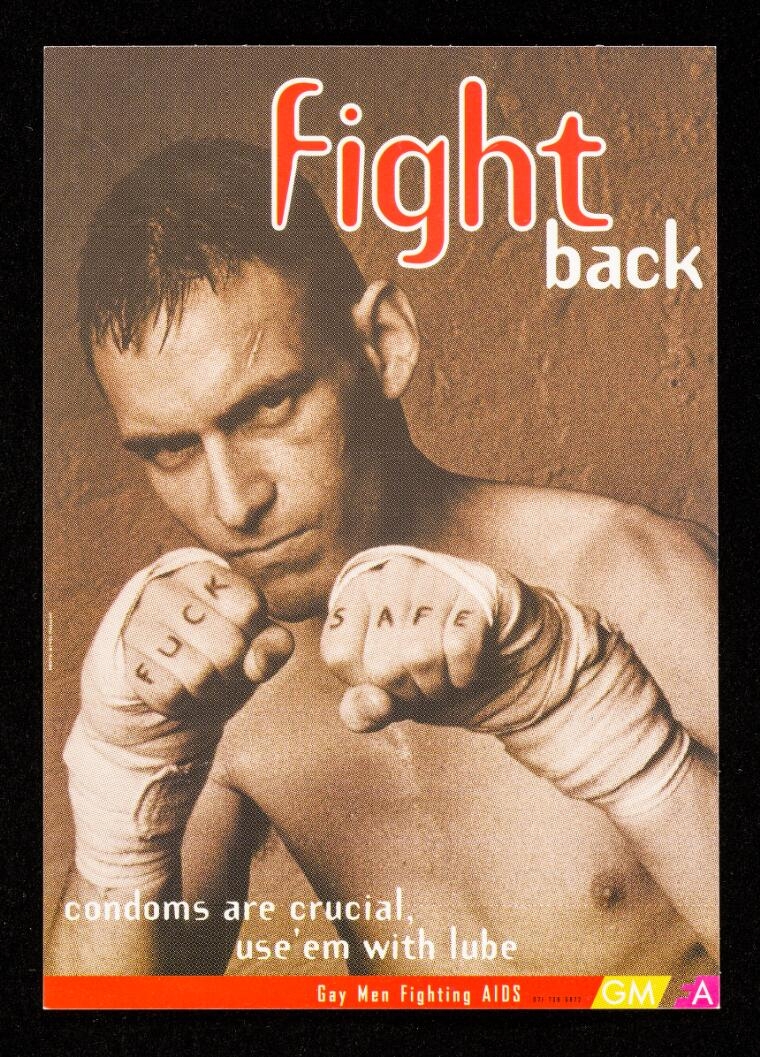

While no longer under legal threat, gay men still faced social ostracism in the later 20th century. This was made worse when the AIDS crisis struck in the 1980s. Men who had sex with men were disproportionately likely to contract the HIV virus, and those who did catch it often faced rejection by their loved ones. This postcard was part of a campaign in London to help protect gay men from HIV by encouraging condom use. Today, drugs like PrEP and PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) can help reduce infection rates, and those who are HIV-positive and receiving treatment can live normal lives. Undetectable viral loads mean an HIV-positive person cannot pass the virus on.

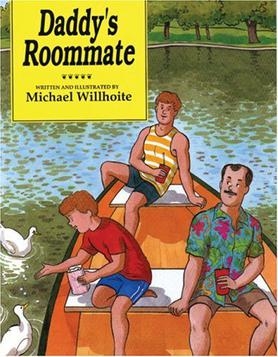

I grew up without any gay role models. Between 1988 and 2003 in England it was illegal for a teacher to suggest that there was anything positive about being gay. Section 28 meant no books with gay role models could be placed in schools. When I was a child in the 1980s and 1990s, if gay men appeared at all on TV or in films, they were either a punchline or a tragic victim of AIDS. Gay people were forced to grow up with little idea that people like them had always existed and were as valid as anybody else. Living without a history is like being a tree without roots – you have nothing to support your growth.

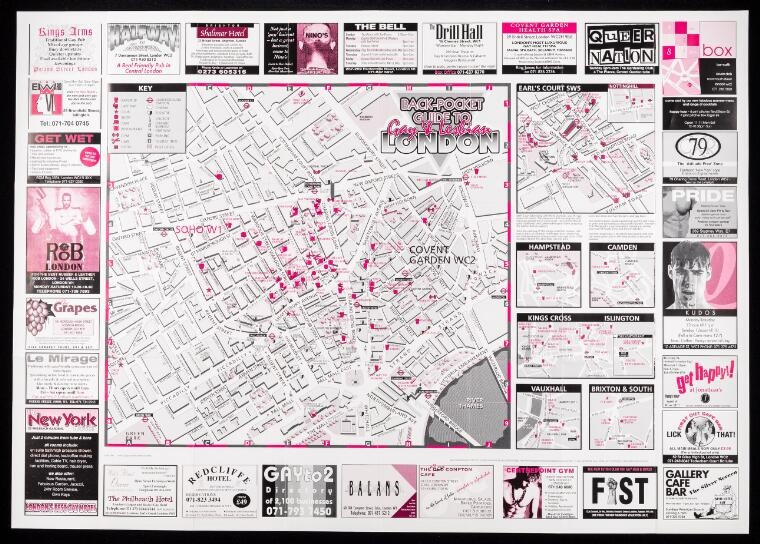

London has been home to places where gay men can meet for centuries. At first these were clandestine clubs or public places where men could meet for quick sexual encounters. It is only fairly recently that gay pubs and clubs have been able to advertise and operate without fear of raids by police. This guide from the 1990s shows just some of the gayest venues in the city.

The first Gay Pride parades were held in London in 1970. Since then they have grown into an annual event that celebrates all aspects of LGBTQ life. The earliest Pride events were overtly political. “What we did was as much a revolution as the Russian Revolution, the Cuban Revolution or the American Revolution… It was about changing the world,” one of the founders of Pride has said. Pride has changed the world for millions of people. There are few thrills like attending your first Pride event, where every member of the LGBTQ+ community is welcomed and can celebrate the pleasure of simply existing in the open.

About the author

Ben Gazur

Dr Ben Gazur has a PhD in biochemistry but gave up the glamour of the lab to be a freelance writer. He specialises in history, science, and the history of science. Ben Gazur is a writer and author. His book about food folklore is currently being crowdfunded. If you support it, you will get your name printed in the book. Click here to find out more.