In the 17th century, a respected professor of natural sciences published ‘evidence’ that dragons existed. Rather than a deliberate attempt to deceive, argues Cassidy Phillips, his belief was genuine, extrapolated from the limited data available at the time.

Fantastic beasts and unnatural history

Words by Cassidy Phillipsaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

One of the most striking and weird works in Wellcome Collection is the ‘Opera omnia’ of Ulisse Aldrovandi. They form a 13-volume set in which the author, incredibly, attempts to describe the whole of the natural world. They are, in many senses, a thing of wonder.

Different volumes cover different subjects: quadrupeds, fishes, sea life, birds, serpents, plants and minerals. Published over a span of nearly 50 years, between 1599 and 1648, most of them run to at least 700 pages. All are illustrated with dozens, if not hundreds, of woodcuts.

The woodcuts are stunning. They’re detailed yet uncluttered in a way I’ve not seen in earlier books. In the anatomy books of the previous century, artists liked to draw écorchés, which could have moonlighted for heavy metal album covers. This did not help their accuracy. There’s no such frippery here, practically no extraneous detail.

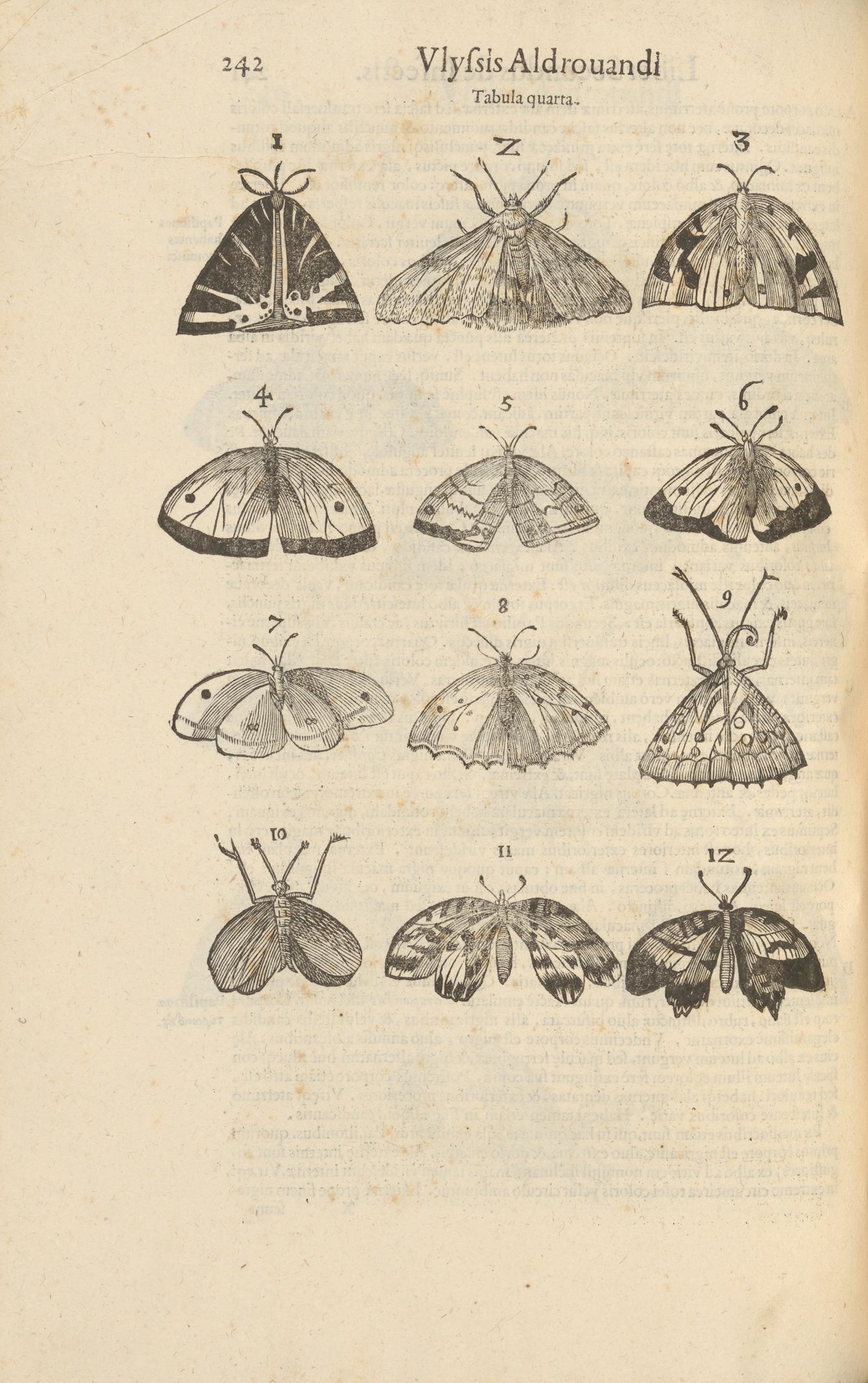

A lot of the drawings – the ones of insects and fish especially – have a clarity and boldness that is geared towards identification: rather than drawing animals for the sake of showing what moral lesson they represented, as bestiaries did, these volumes looked outward to try and see what these animals actually were.

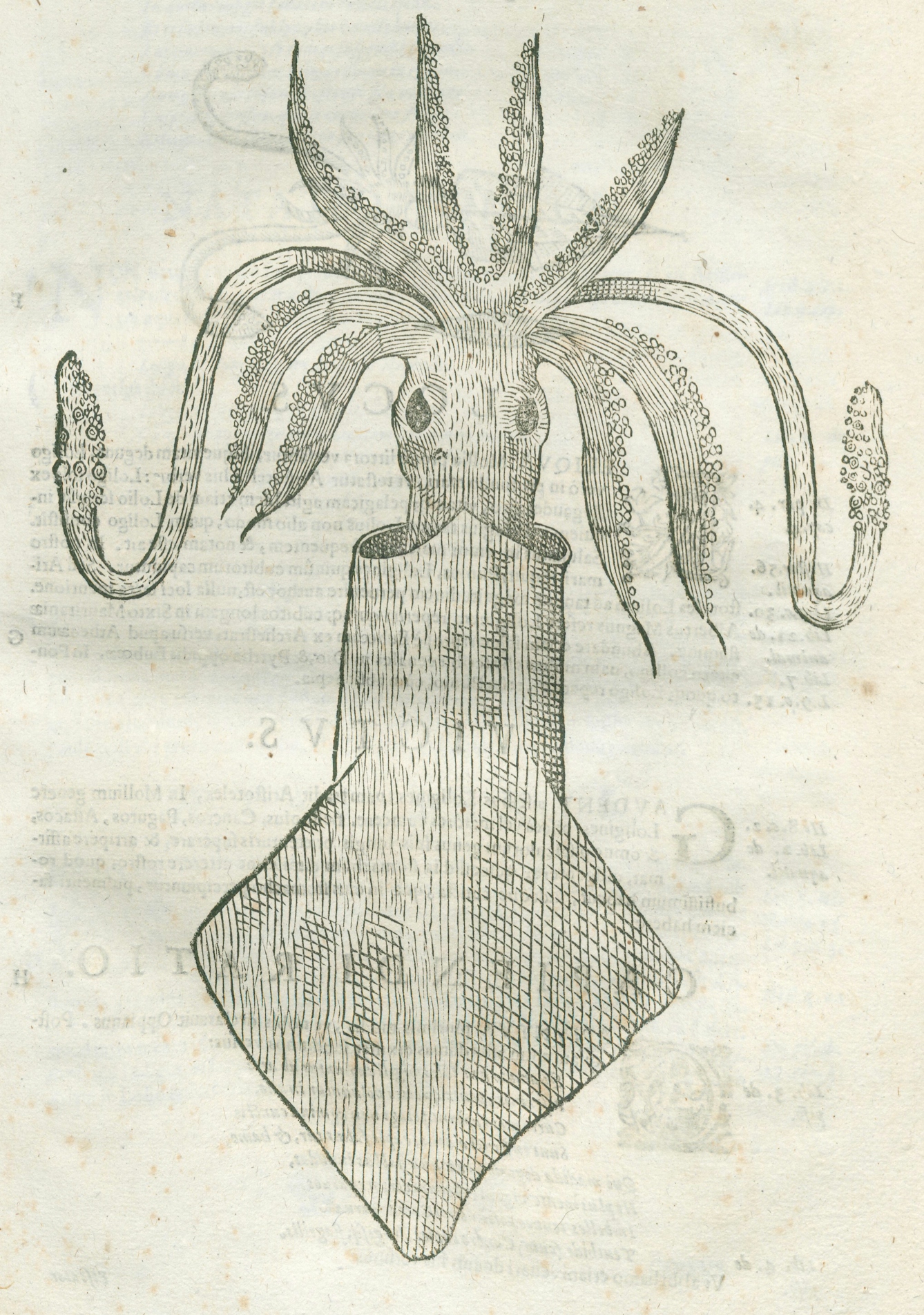

Many of them hold up today: you can look at an illustration of a perch and still say, “Yes, that looks like a perch.” You can look at an illustration of some mutated chicory and still say, “Yes, that’s some actual mutated chicory: somebody copied that from life.” Look: this is clearly a squid of some sort. Yes, that’s a wolf. Those are ammonites, no doubt about it. I’d say that’s probably meant to be a hippo.

Recognisable creatures

This lobster is remarkable for the beautiful detail of its depiction rather than any bizarre traits.

Aldrovandi’s perch would be as familiar to modern fishermen as those of his own time.

This chicory plant looks just like those we might spot at the side of the road or grow in our gardens today.

The modern squid looks precisely like this illustration from four centuries ago.

But the more you look through the books, the more things seem amiss. Suddenly you notice that there’s a horse with human hands. And don’t even get me started on the dragons in the book about snakes!

This is the exasperating, thrilling thing about these books: they seem to make little or no distinction between things that definitely exist, things that might exist and things that are, to our eyes, complete cobblers.

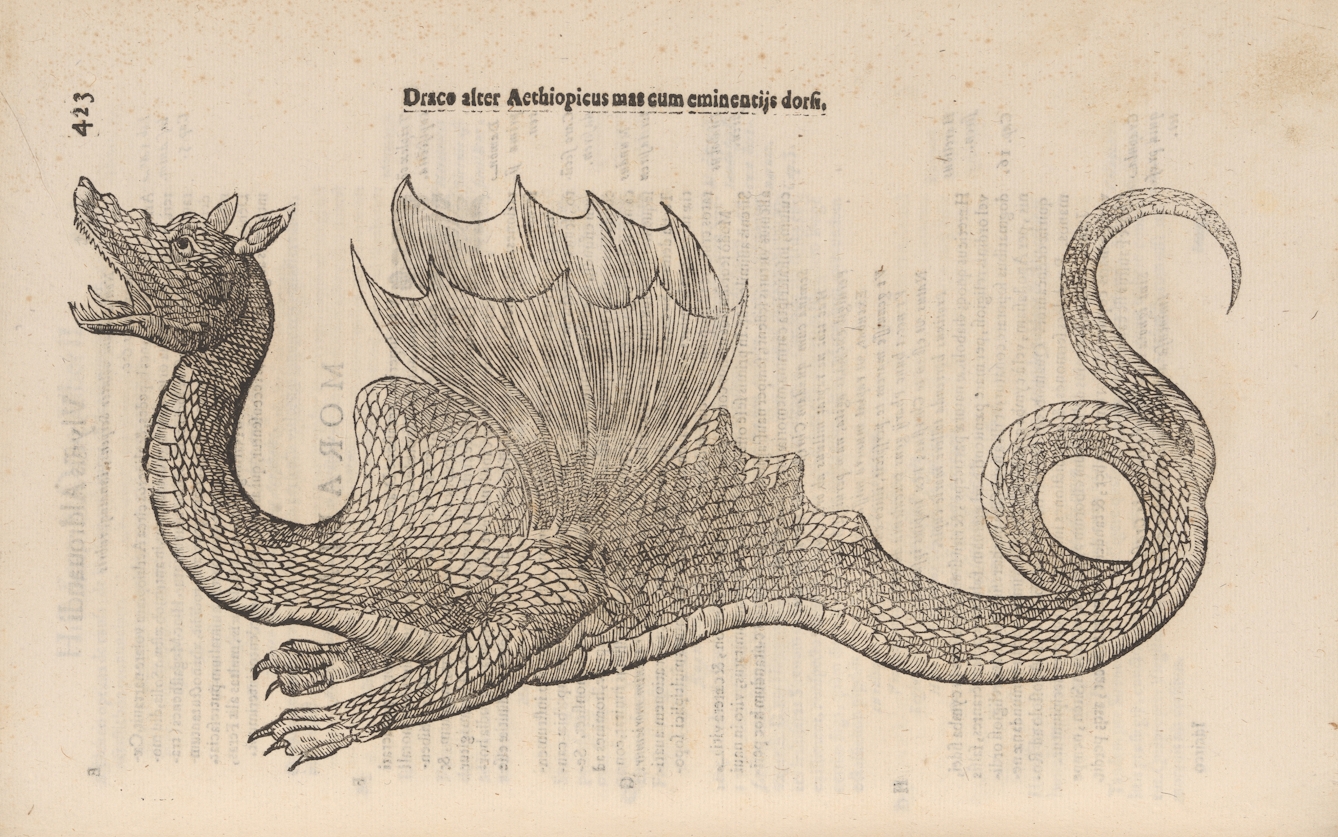

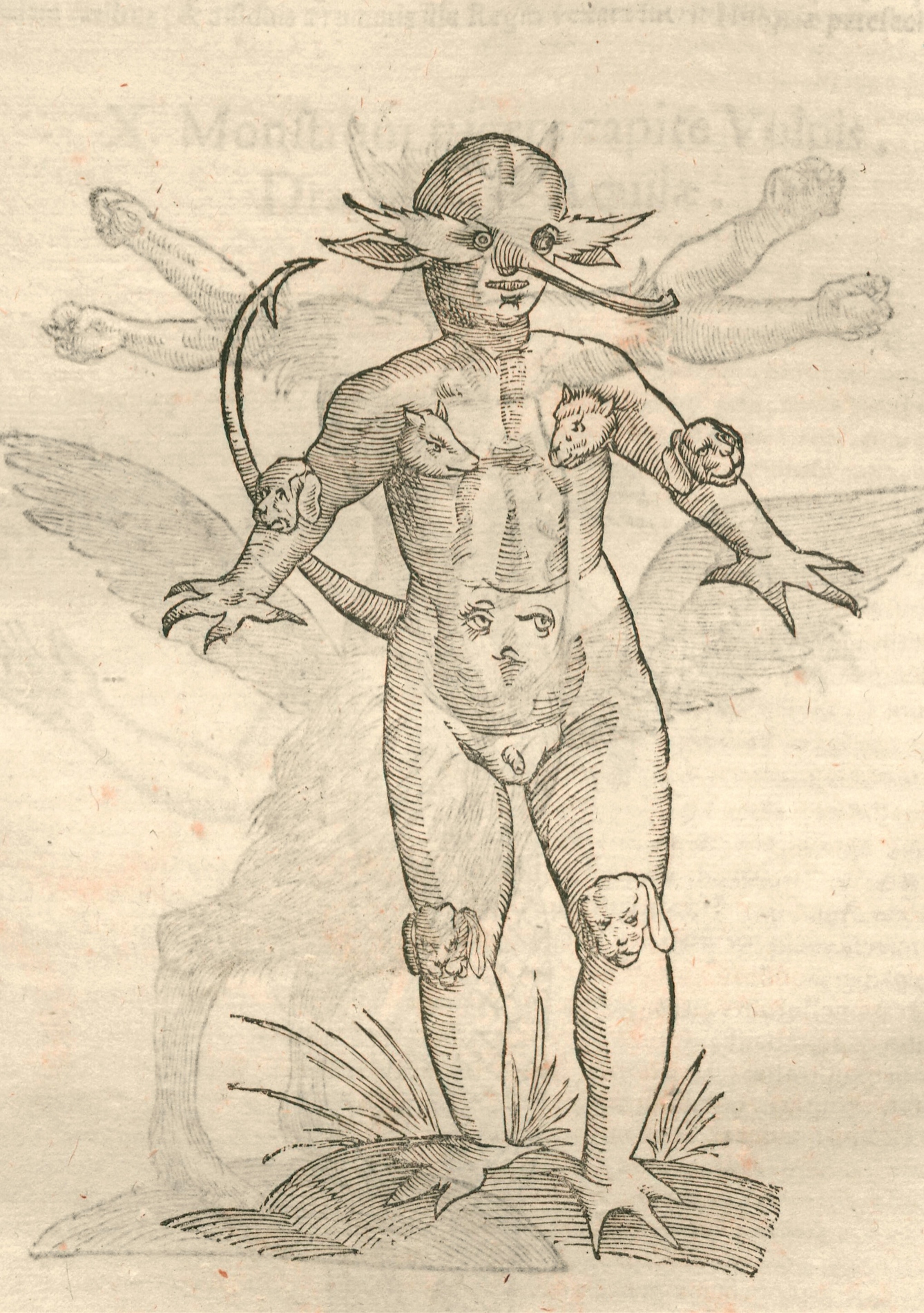

Aldrovandi debunks one of his dragons – a charming creature rather resembling a melted rhino – as a Jenny Haniver (a fake). But his Ethiopian dragon is presented as the real deal. And in his volume on (mostly) abnormal creatures, relatively realistic images of developmental abnormalities such as a chicken with three legs sit alongside a deer that has seemingly stepped out of sci-fi horror ‘Annihilation’ and a child sprouting puppy heads. What’s going on?

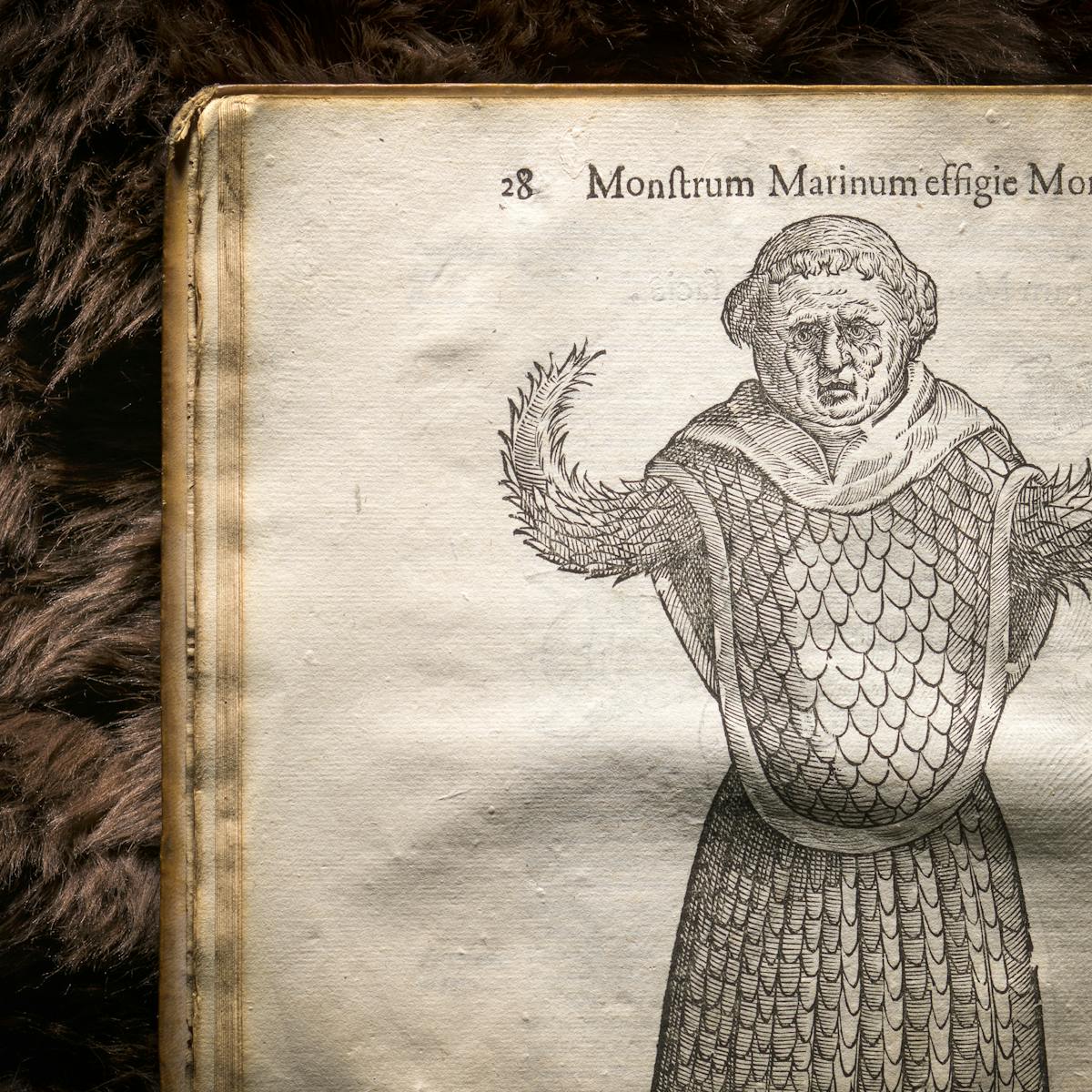

Monstrorum historia

Aldrovandi includes several examples of dragons in his books – this is one of the more magnificent.

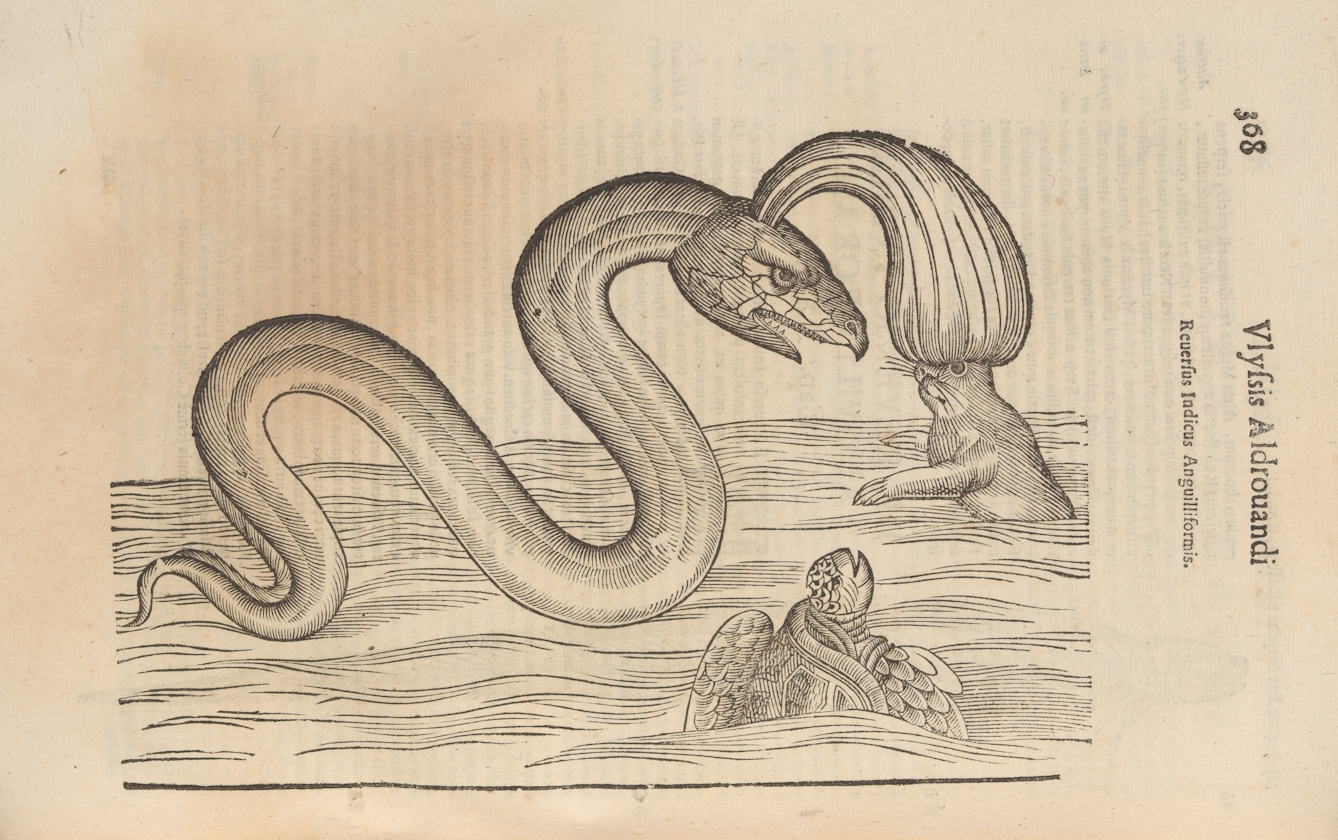

It’s hard to tell what might have inspired this creature depicted accosting a crustacean. On closer inspection you can see that it has a horse-like face and could be a creative take on a seahorse.

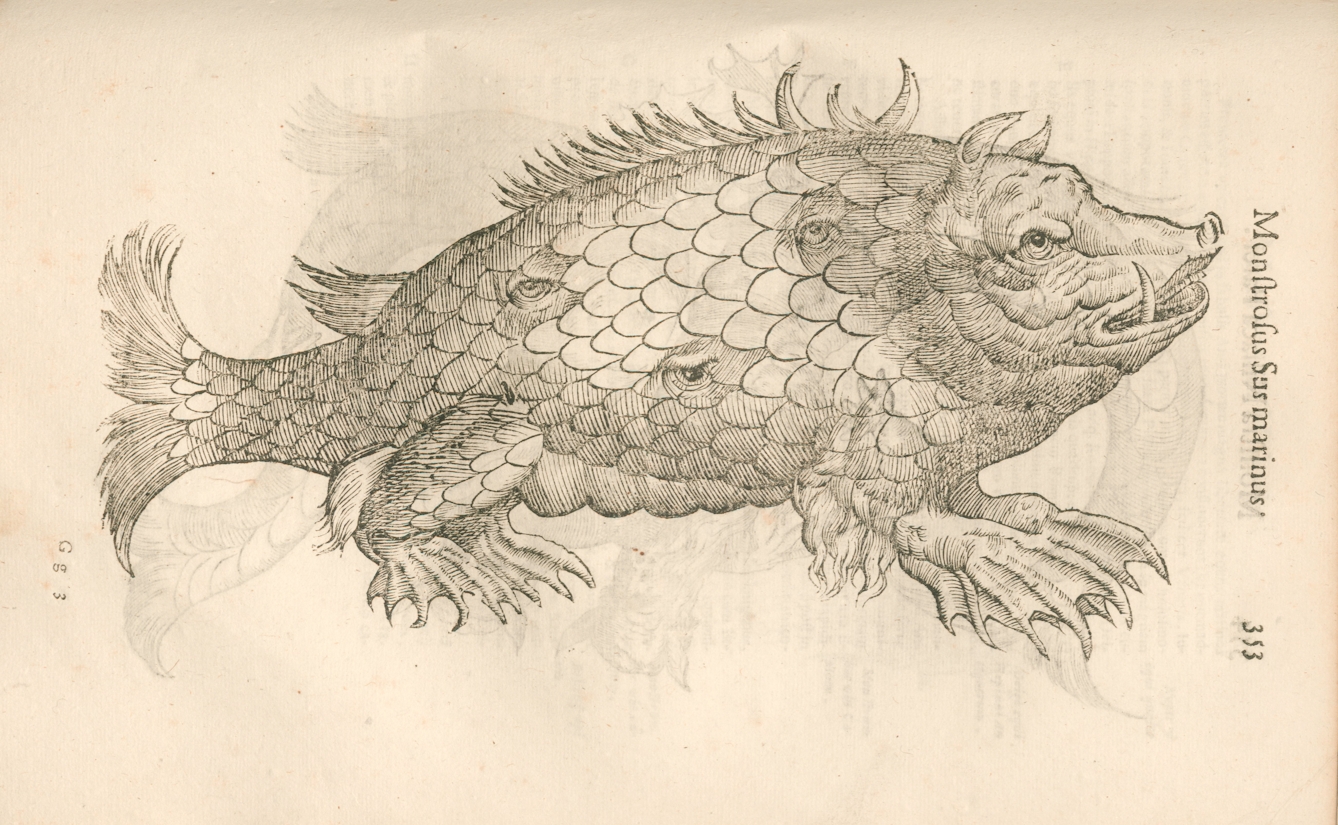

Gaze into some of the many eyes of this half hog, half fish chimera. Aldrovandi also helped spread word of sea monsters that could devour whole ships.

Puppies are adorable, and children can be cute. However, combining multiple puppy heads on the body of a child is somehow not quite as adorable as logic indicates it should be.

Aldrovandi was one of Europe’s first great naturalists: the story goes that he acquired a taste for it in 1550, while under not-quite-house-arrest for heresy. In the decades that followed, he became the University of Bologna’s first Professor of Natural Sciences, and amassed a collection of many thousands of objects. One account says 7,000, another says 18,000 – either number is far greater than any ‘regular’ cabinet of curiosities from that time. These objects came to form the backbone of his books.

Aldrovandi was a great believer in direct observation: he’s been quoted as saying, “I have never described any thing without first having seen it with my eyes.” He also claimed to possess the remains of a baby dragon in a jar. I don’t think it’s unfair to say that these statements, taken together, raise certain questions for modern readers.

Seeing is believing

For all his aims of objectivity, Aldrovandi lived in a time where objectivity was difficult to achieve. In previous centuries, the believability of a claim was based on the authority of the person who said it was true. Aldrovandi was a part of a Renaissance-era movement to overturn this, hence his statement about the importance of seeing for yourself.

But it was very difficult to insist on direct observation at this time and to record everything in the natural world: concrete evidence of many creatures was scarce – it was difficult to transport a fish halfway across the world, let alone a sea serpent. So some of the items in his collection were only partial specimens of a plant or animal accompanied by a description of the entire thing; some were apparently just paintings.

Sometimes, it seems, he may have been forced to rely on earlier texts, as much as he may have disliked it: several of his quadrupeds were reproduced from Conrad Gessner’s banned ‘Historia animalium’. Less polished versions of many of the illustrations in Aldrovani’s ‘Monstrorum historia’ can be found in Ambroise Paré’s ‘Des monstres et prodiges’ (1573), and he also includes a version of Pierre Belon’s 16th-century plates comparing human and avian skeletons.

River eels do exist, but it’s unlikely whether one has ever captured its prey in the way that this turtle is observing.

It’s worth pointing out that Aldrovandi only oversaw the production of the first few volumes of his work: he died in 1605. It’s the penultimate volume, compiled decades after his death by professors who may, ironically, have been trading on Aldrovandi’s established authority, that contains the most fanciful specimens and the most recycled material. Then again, even the first volume includes a lion-tailed rooster and a small stone that was miraculously found to contain the likeness of a snake, with no human intervention – there’s no way we can let him off the hook for those.

From one perspective, he was helping collate and disseminate these ideas, which was clearly valuable work. Aldrovandi’s own plates appear in volumes of natural history well into the 18th century. This still goes against his claims of direct observation though, and his success meant that he propagated a lot of false information. Consider the sea monk or the Monster of Ravenna.

Aldrovandi was steering away from the world known to medieval Europe, but he was still building on Gessner’s taxonomy of animals, which in turn was built on Galen’s writings from the second century CE. He was unable to see – had no reason to intuit – anything like the modern phylogenetic structure, which would have provided a framework for his natural history.

Scientific method, which brought with it the ability to verify claims, was still a distant dream at the time, and even if it had been developed, it might not have been so useful: Aldrovandi didn’t need a means of replicating experiments so much as a chest freezer to preserve his specimens.

Turning fiction into fact

Scientific progress is iterative. It is based upon taking the knowledge we already have and pushing it beyond its current limits, something that Aldrovandi did to great effect with the work of Gessner, Belon, Paré and, doubtless, others. It’s also based on identifying and correcting the mistakes of those who came before us and avoiding them ourselves.

Butterflies, with their remarkable feat of metamorphosis from their earlier caterpillar form, seem fantastical but are real – no wonder Aldrovandi was unsure where the boundaries between reality and imagination lay.

So, in that spirit, where did Aldrovandi go wrong? Where could his dragons have come from? Let’s run through the possibilities.

First, Aldrovandi could not infer an entire creature from a few paltry body parts – which is perfectly reasonable (there was even a fable about it!), but must have made some of his specimens quite incomprehensible.

Second, due to the time in which he lived, he was unable to verify his sources – and the world is deeply strange. Without strong evidence, why should anyone believe in the existence of a spotted hyena but not a horned hare?

Third, he was working without the massive contextual advantage that modern life sciences give us when studying zoology – and, lacking the taxonomies and genetic techniques we take for granted, he was always in danger of misinterpreting and misapplying what he knew.

Finally, he claimed to hold knowledge he clearly did not possess. Rather than acknowledge the gaps in his understanding, he took what he had and packaged it up as fact. To me it’s that last point which is the most damning, really. I mean, I can’t read Latin – I’ve relied on other people’s translations to understand this work – and, not being a trained historian, I’ve had to piece together the historical context of these books as best I can, using whatever sources I could find. But believe me: this is definitely, almost certainly what happened.

About the author

Cassidy Phillips

When he’s not rummaging around in the stacks, Cassidy Phillips helps digitise library material from the Wellcome Collection.