Neck pain, eyestrain, sleeplessness, self-absorption, mental health problems – and, occasionally, death. We’re only just waking up to the damaging reality of smartphone addiction.

Self-obsessing in the age of selfies

Words by Stevyn Colganaverage reading time 10 minutes

- Serial

New technologies are often viewed with suspicion. In 1877, the New York Times attacked the newfangled telephone for its invasion of privacy and, in 1889, the Spectator magazine described the telegraph as “a constant diffusion of statements in snippets” that would kill the art of conversation. When Marconi developed wireless radio he worried, “Have I done the world good, or have I added a menace?” and many people decried the invention of both cinema and the television. Famously the head of IBM, Thomas J Watson, insisted in 1943 that “there is a world market for about five computers”.

In its early days, the internet also came in for scorn. While researching this essay I came across an archived article from a 1995 issue of Newsweek in which the author scoffs at the idea of online shopping: “So how come my local mall does more business in an afternoon than the entire internet handles in a month?” questions the author. “Even if there were a trustworthy way to send money over the internet – which there isn’t – the network is missing a most essential ingredient of capitalism: salespeople.”

As someone wise once said, hindsight is always 20/20. Few people could have predicted just how much the World Wide Web would come to impact everyday life. And not always for the better.

One of the most common uses of the internet – accounting for around 30 per cent of all time spent online – is interaction via social media, and some people are now suggesting that it has become a form of intoxicant with the potential for addiction. There have been a number of studies that suggest that this is so.

Low self-esteem and ‘selfitis’

A condition that the media has dubbed ‘selfitis’ – the need to post pictures of yourself online – has been proposed in recent years and articles regarding the condition have appeared in many magazines, newspapers and journals. In one, Dr Janarthanan Balakrishnan, from Nottingham Trent University’s Department of Psychology, says: “Typically, those with the condition suffer from a lack of self-confidence and are seeking to fit in with those around them, and may display symptoms similar to other potentially addictive behaviours.”

The origin of the story was that the American Psychiatric Association had allegedly classed ‘selfitis’ as a mental illness. This proved to be a hoax but, as many commentators pointed out, wasn’t there some truth at the heart of it? Had the taking of selfies become intoxicating to the point of obsession for some?

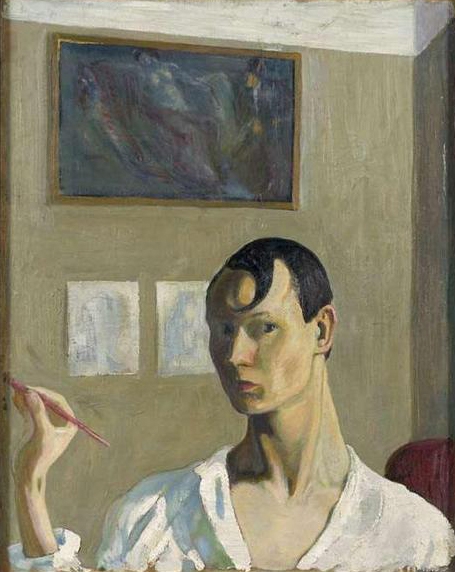

Whether we call it vanity, narcissism, or selfitis, as this image from the 14th century shows, the idea that people are worryingly self-obsessed is an age-old concern.

Twenty-two year old Junaid Ahmed has over 50,000 followers on Instagram and posts around 200 photos of himself online every day. He admitted to the BBC that he had undergone cosmetic surgery as a result. “I used to be quite natural,” he says. “But I just think, with the obsession with social media, I want to upgrade myself now. I’ve had my teeth veneered, chin filler, cheek filler, jawline filler, lip filler, Botox under the eyes and on the head, tattooed eyebrows and fat freezing.”

Of course, this isn’t just an issue for the male half of the population; as many as nine in ten teenage girls say they are unhappy with their bodies too. Women also take more selfies than men and are more likely to edit their images to make themselves look thinner.

As Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett wrote in the Guardian, “It’s unbelievably easy to doctor a photo. I do it to a photo of myself taken in the garden last month, and in under five minutes I am slimmer, browner, better. I wouldn’t be a product of my environment if I didn’t think the ‘after’ image trumped the ‘before’. The difference is, I would never post it claiming to truth; lots of younger girls would.”

Euphoria, addiction and withdrawal

Whether or not ‘selfitis’ is a unique condition is debatable, but a 2016 review of the literature on selfie-taking and mental health concluded that excessive selfie-taking and posting was most associated with low self-esteem, narcissism, loneliness and depression. It’s easy to see why someone with existing psychological issues might use social media as a way to temporarily assuage negative feelings about themselves. There is something euphoric in getting ‘likes’, follows, retweets and positive comments from strangers.

We now live in a culture where many people believe that the better looking you are, the better life you have. People are using selfies as new way to express their identity; to create a ‘better’ version of themselves. This can mean spending hours learning to use make-up effects like ‘contouring’ to ensure that each selfie is perfect. It can also, as in the case of Junaid Ahmed, involve cosmetic enhancement. But it’s not just how good you look; it’s also how good your life is. People take selfies on holiday, at rock concerts, even at the theatre (often to the annoyance of those around them). For many, recording the fact that they were there has become more important than the actual experience.

Are selfies significantly different from self-portraits, created by artists spending hours gazing at themselves in the mirror and adjusting their appearance to express their identity?

However, there is always a downside to any such intoxicating activity. Prolonged or continual use can lead to dependency to maintain the good feeling. As another recent review of the existing literature states, “Regarding internet addiction, neuroscientific research supports the assumption that underlying neural processes are similar to substance addiction.”

And there are other negative aspects to consider. There are plenty of stories of people who have had accidents while their eyes are glued to their phone screens, such as the two men who were hospitalised in 2016 after falling off a cliff in Encinitas, San Diego, California, while playing Pokémon Go. Or the 19-year-old Missouri man who caused a multiple vehicle accident in 2010, resulting in two deaths and 38 serious injuries, due to texting (his phone records revealed that he’d sent five text messages at the time of the pile-up). Or the Texas woman who, in 2015, failed to spot that her children were drowning as she sat nearby engrossed in her phone.

People also engage in dangerous behaviours to get that perfect shot – since 2011, over 250 people worldwide have died while taking selfies. And there are effects on the body too; a 2017 study examined 250 Indian students aged 18–25 and reported that 30 per cent had lower back ache, 15 per cent suffered stress, 20 per cent suffered from cervical spondylitis, 25 per cent suffered from headache, and 10 per cent suffered from ‘selfie elbow’ (tendonitis). The study could not conclude that these effects were specifically due to use of mobile phones but it was strongly believed to be contributory.

People taking selfies can be oblivious to dangers around them: more than 250 people have died while attempting to take selfies.

The new separation anxiety

Psychologists have also found that genuine withdrawal symptoms can occur when, for some reason, a person cannot access their smartphone. “As smartphones evoke more personal memories, users extend more of their identity onto them,” says a 2017 research paper. “When users perceive smartphones as their extended selves, they are more likely to become attached to the devices.”

And, as Dr Larry D Rosen points out: “At least four separate studies in four different labs using four different methodologies have demonstrated the same general effect. […] If someone is separated from their phone they get anxious.”

One study by the UK Post Office to evaluate anxieties suffered by mobile phone users gave the condition a name: nomophobia (an abbreviation of ‘no-mobile-phone phobia’). The study found that nearly 53 per cent of mobile phone users in Britain tend to be anxious when they “lose their mobile phone, run out of battery or credit, or have no network coverage”. More recent research from the US recorded anxiety in students who had to give up their phone for just a day.

Of course, it’s not separation from the phone itself that’s the issue; it’s not being connected to others. A 2016 study found that the typical smartphone owner interacts with other people via their phone an average of 85 times per day, including immediately upon waking and just before going to sleep. Some even check their phones in the middle of the night.

The behaviour is more prevalent among the young, and a 2017 report in the Journal of Youth Studies states that: “One in five young people say they wake up during the night to check messages on social media, leading them to be three times more likely to feel constantly tired at school than their classmates who don’t use social media during the night.”

And obsessive phone use has been connected with a more sinister trend than lost sleep. A recent study found that nearly half of young people who spent five or more hours per day on their phones had experienced suicidal thoughts, compared with only 28 per cent of those who spent an hour on their phone.

Intoxication and moderation

This does skirt perilously close to the idea of obsession or addiction. But what about intoxication? Can social media affect us physically and mentally in the way that alcohol or heroin can?

A 2017 study by the University of Texas (Austin) found that people’s ability to hold and process data is impeded by the presence of their smartphone. Participants who kept their phones in another room, or on their person but out of sight, performed better than those who kept their phones on the desk while taking the same cognitive tests. It seems that the presence of our smartphones stifles our ability to concentrate on a task fully, just as a few drinks would.

This, naturally, could have a knock-on effect for education and for business. So how do we tackle it? The answer, unsurprisingly, is moderation. The aforementioned Dr Rosen and others believe that planned periods of separation “may allow consumers to perform better, not just by reducing interruptions but also by increasing available cognitive capacity”.

The internet has been with us, in an everyday usage sense, for less than three decades, but we are starting to see an impact upon users’ mental and physical health. GPs are seeing more and more cases of ‘text neck’; the neck pain and damage sustained from looking down at mobile devices too frequently and for too long. Digital eyestrain is also an issue.

Look up from your screen

The Royal Society for Public Health and the Young Health Movement is calling for action to reduce the potential negative impact of prolonged internet usage. It recommends the introduction of pop-up ‘heavy usage’ warnings on screen, and for social media companies to be more proactive in identifying users who could be suffering with mental health issues.

There are existing treatments for addiction, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, but with the growth of social media platforms and the increasing use of smart mobile devices, the intoxicating effects of social media can only become more pronounced.

Based upon the emerging evidence, it does seem that perhaps we should be paying more attention to the people around us than to the people behind the screen.

About the author

Stevyn Colgan

Stevyn Colgan is an author whose debut novel, 'A Murder to Die For', was shortlisted for the Penguin Books’ Dead Good Readers’ Awards. For more than a decade he was one of the ‘elves’ that research and write the TV series 'QI', and he was part of the writing team that won the Rose d’Or for BBC Radio 4’s 'The Museum of Curiosity'. In his previous career he was a police officer in London for 30 years.