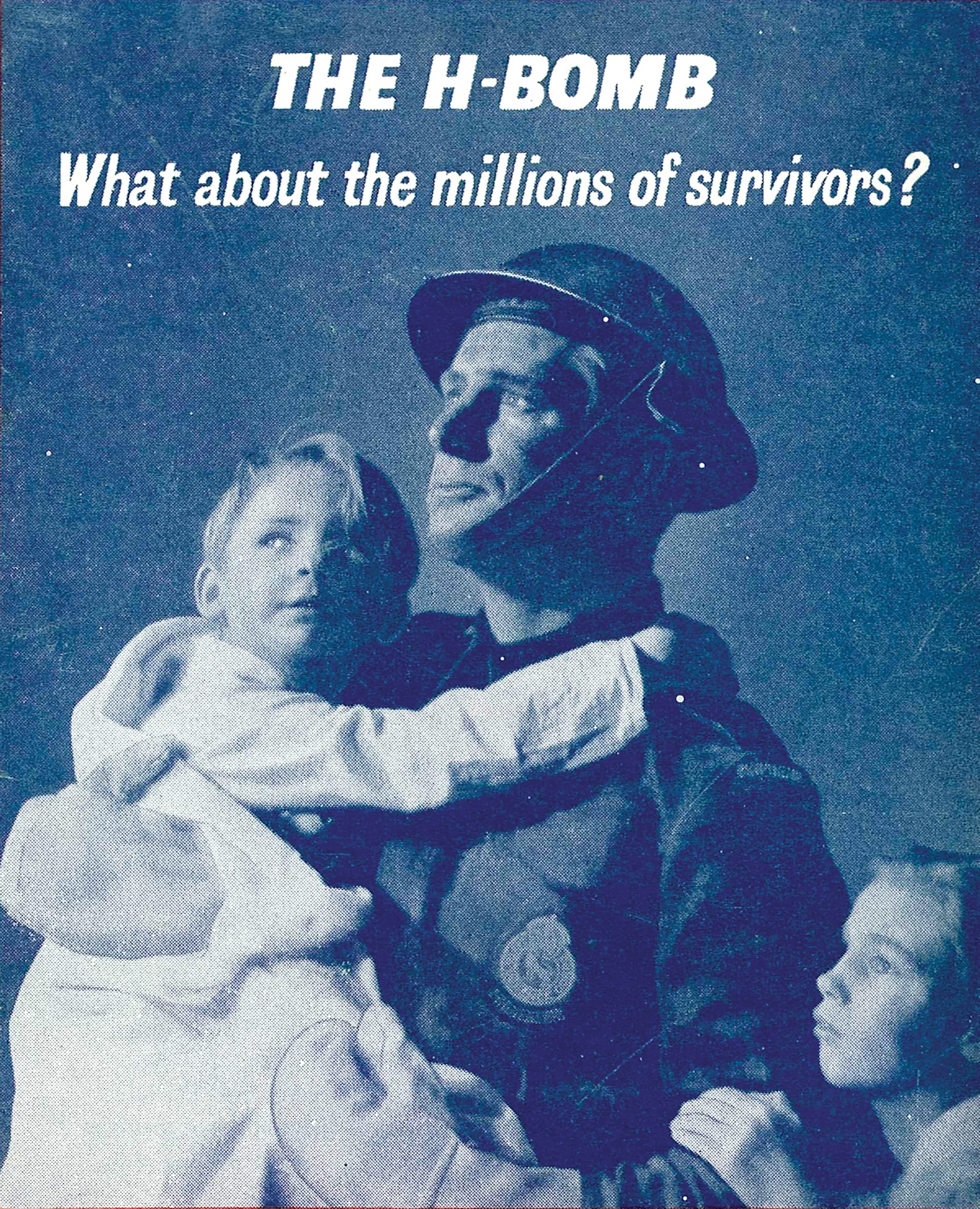

How would you hold up psychologically if a nuclear bomb was dropped? Many would crumble, but if you happened to belong to a special group comprising just 1 per cent of the population, you might actually do very well.

Burns, radiation sickness, blast injury: these are the effects of a nuclear attack that people learned to worry about during the Cold War. But what about the impact on mental health? It’s difficult enough to picture Britain after a nuclear attack; it’s harder to imagine how you would feel as a survivor. The fortunate few might get away with mild anxiety and depression; at worst, you could be a shell of your former self.

For those who survived a nuclear attack, psychological problems might be as pressing as physical ones.

The psychological impact of nuclear attack was poorly understood and barely researched until the early 1980s. That meant most public information didn’t provide any useful guidance or support.

Greater Manchester Council’s ambiguously titled ‘Community Self-Help Survival Guide’ was one of the few publications to consider the question, and it offered some possible remedies. “The shock of a nuclear attack, fear, uncertainty as to what is happening… no traffic noise, church bells, countryside or city background noises – could affect normal behaviour,” it said. To combat the psychological impact, the authors suggested listening to radio news broadcasts, playing card games, and – oddly – discussing how life would change post-apocalypse.

This homespun booklet was very much the exception. The British Medical Association’s extensive 1982 study of the medical impact of nuclear war only made passing reference to the impact on mental health. In fact, even governments had carried out little research into the topic.

Predicting reactions

That changed in 1981, when the Home Office decided to undertake its own study. Its Emergency Planning Division wanted to understand how ordinary people would react before, during and after nuclear attack. This information could help predict the implications for maintaining law and order, preventing panic, and ultimately ensuring continuity of government.

Researchers created a series of classified internal reports, with the first appearing in autumn 1981. Drawing on reactions to the Blitz, the 1957 nuclear accident at Windscale, the Summerland leisure complex disaster in 1974, and even the 1977 New York blackout, they tried to paint a picture of how the British public might act under the threat of nuclear attack, and in the aftermath.

Denial and panic

First, they questioned whether ordinary people would do what they were told. Even if adequate shelter was available to the public – which in 1980s Britain it wasn’t – it was thought that most would refuse to believe they were at risk. They would continue to live their lives in a state of denial, with the majority failing to seek protection until they saw explosions or fires, or smelled noxious odours for themselves.

This would have been particularly problematic in the case of a nuclear strike, since the most lethal post-attack danger – radioactive fallout – wouldn’t look, sound or smell alarming. False alarms, or a lengthy period of tension building up to an attack, would only deepen the denial effect, making people even less likely to respond to official warnings when they came.

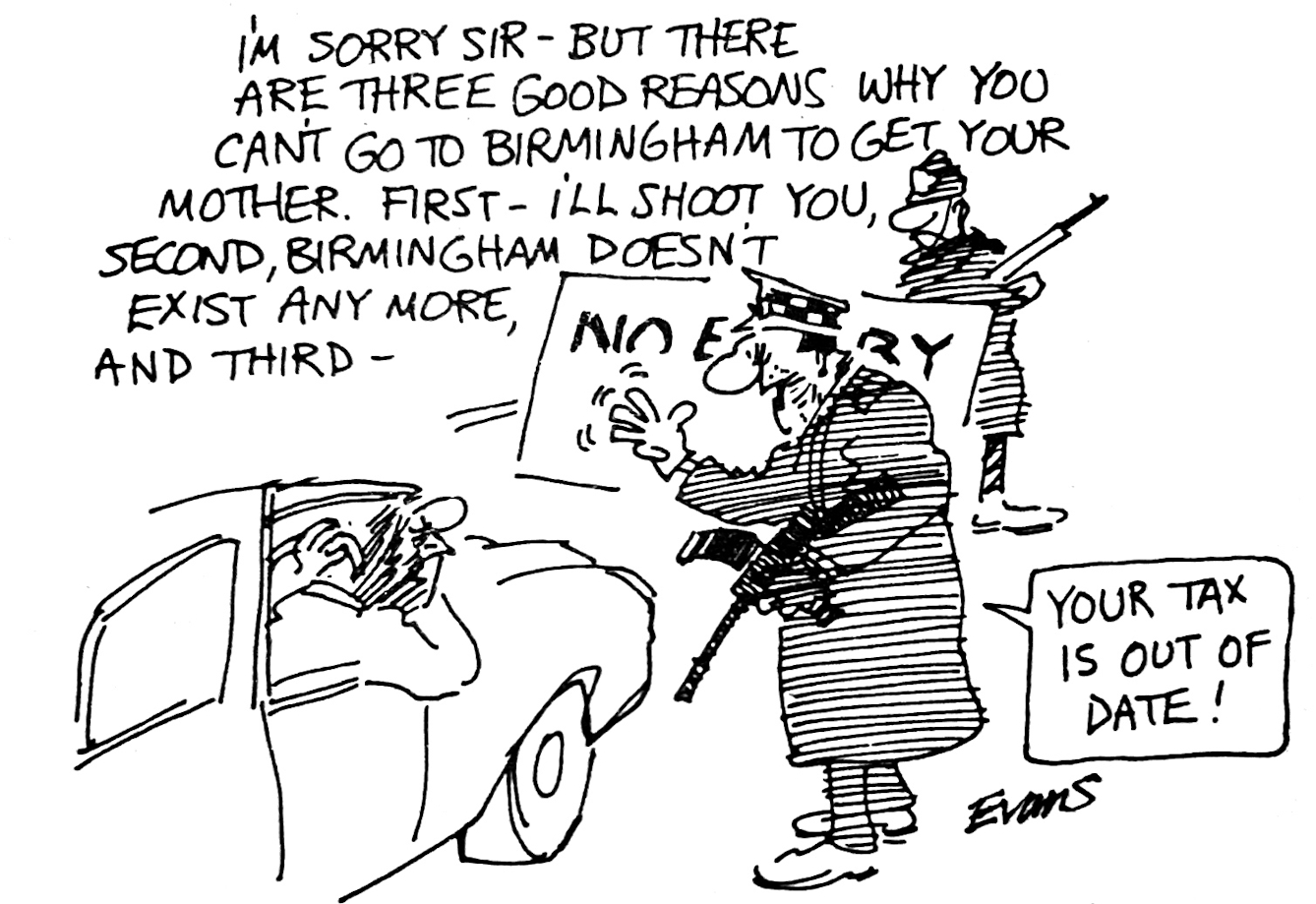

Curiously, the authors determined that panic was very uncommon in war, so long as people felt prepared and well-informed. Fleeing cities, they argued, wasn’t evidence of panic, but rather the pursuit of “a rationally calculated goal of safety”. However, officials might interpret this flight as panic, and on that basis restrict movement and access to information. Counterintuitively, these actions would create the conditions that fuelled genuine panic, with people feeling uninformed, confused and trapped. That vulnerability would derail rational thought, blocking natural, positive instincts for dealing with disaster.

There might be difficulty maintaining official routines in the aftermath of a nuclear attack.

Disaster syndrome

After experiencing the nightmarish impact of nuclear war, many survivors would experience “disaster syndrome”. This is manifested as anxiety or depression, ranging from the mild to the debilitating. A small number would escape this fate altogether, and it was predicted that these people would begin the process of reconstruction. Those experiencing mild disaster syndrome would attempt to rebuild, but in small steps – losing the ability to think beyond their current situation, leading to anger, frustration and hostility. Those who were most badly affected would be apathetic, depressed and agitated. Some in this final group would experience “uncontrolled tears and expressions of sorrow”, while others would find themselves excessively talkative, continually making unfocused, ineffective attempts at recovery.

Once initial relief and reconstruction had taken place, the report’s authors predicted a further change in behaviour: people would start to blame those in authority for what had happened (although, arguably, this wouldn’t be irrational). Hostility between groups and individuals would increase, and scarcity of resources would lead to problems of law and order.

Psychopaths in the spotlight

The Home Office researchers believed that antisocial behaviour “could be expected within the groups who exhibited similar behaviour patterns in peacetime”. While this was a reference to criminal activity, one particularly antisocial group was also singled out for their psychological resilience: psychopaths.

Making up around 1 per cent of the population, psychopaths were expected to show “no psychological effects in the communities which suffer the severest losses”. The report added: “They are very good in crises, as they have no feelings for others, no moral code, and tend to be very intelligent and logical. Pre-strike, the only solution for these people is to contain them; post-strike, the authorities may find it advantageous to recruit these people, as they could prove an exceptionally valuable resource.”

On completion, the reports were briefly used to inform Exercise REGENERATE, a game designed for emergency planning, which used a computer program to simulate post-attack scenarios. However, they proved controversial within the Home Office and were shelved. Having sought to find out what life would be like after a nuclear attack, the prediction of a listless, frustrated and angry population, “weak, immobilised and surfeited of suffering”, psychologically scarred by unthinkable terror, and led by psychopaths, simply wasn’t anyone’s cup of tea.

About the author

Taras Young

Taras Young is a researcher and writer interested in weird, hidden and forgotten ideas. He is the author of Apocalypse Ready, a new illustrated history of 20th century public information on pandemics, natural disasters, nuclear war and alien invasion.